The 'games of the world' are an engrossing subject, specifically when you look past the dominant geographical triumvirate of America, Japan, and Europe (actually a collection of distinct territories, unfairly homogenised into a single label). My first professional article was in GamesTM #27 covering the unique gaming scenes in South Africa, Brazil, Russia, Iran, and other countries. A few years later I started the weekly Games of the World section on Hardcore Gaming 101, promising anthropological studies from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe (sadly the HTML is now broken; browse it on Wayback). I stopped updating in 2012 but, in 2015, Mark Wolf of Concordia University wrote an academic book titled Video Games Around the World. We corresponded briefly, discussing his research. As I said, the exotic markets outside of our mainstream domestic one are fascinating and a personal passion.

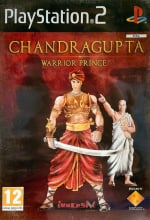

So when stumbling across Chandragupta: Warrior Prince, a game about the real-life emperor of ancient India, developed in India, specifically for the Indian market, there's a strong urge to know more. According to MobyGames, it had a PSP release in 2009 and a PS2 release in 2011, with only India listed under countries. Which is odd, given that the PS2 version has a PEGI rating on the cover. Searching online, there's not a lot of information. Vague release dates, some YouTube videos of the ISO being emulated, and a Reddit thread asking about it – plus a few overpriced copies on eBay.

From the very first screen, which asks if you want to continue in English or Hindi, Chandragupta is a culturally rich artefact. Based on real events, the cinemas are voiced by professional actor Pralay Bakshi and provide an atmospheric narrative as you explore different chapters in the eponymous emperor's life. Mechanically it plays like a 2.5D evolution of the original Prince of Persia; a cinematic platformer with polygonal character models and scenery, sword combat, the ability to fire arrows at enemies in the fore- and background, special attacks that affect the whole screen, bosses, puzzles, and a light RPG-style upgrade system.

Wolf's aforementioned book has a 13-page chapter on India written by Souvik Mukherjee, which mentions Chandragupta. Mukherjee explains that the history of games in India is largely unrecorded, with the earliest example possibly being PC FPS Yoddha: The Warrior (1999). Astonishingly Gadgets360 has an interview with its programmer Vishal Gondal and designer Ninad Chhaya – there are only two very blurry screenshots. Mukherjee also cites the slightly later Bhagat Singh on PC (2002); this is fairly easy to find on abandonware sites.

On page 238 of the book Mukherjee then examines the arrival of official Sony-licensed Indian-developed PS2 games:

"Indigenous games, drawing on Indian ethos, first arrived on the PS2 platform with Hanuman: Boy Warrior (2009), developed by Aurona Technologies and launched by Sony Computer Entertainment Europe. Another PS2 game with an Indian connection is Singstar Bollywood (2007), which is available in Hindi, and there are plans to include more Indian languages. Other PS2 and PSP games with a local flavour are Trine's Street Cricket (2010), and Immersive games' Chandragupta (2011), which is based on the historical battles of Indian emperor Chandragupta Maurya."

Mukherjee then goes on to quote Atindriya Bose, head of India operations for Sony Computer Entertainment, from now defunct website GamingExpress. Bose stated: "The market is maturing very fast in India and the product quality has improved significantly. All our developers, Immersive, Gameshashtra, and Trine, have done considerable development on PSN and have done substantial outsourcing work as well. [...] It is only a matter of time for our developers to start on the PS3 as well."

Hanuman: Boy Warrior looks especially interesting, but unfortunately, there are no listed credits for the team at Aurona Technologies. Chandragupta: Warrior Prince, by Immersive Games, thankfully has detailed credits. This is a good start for finding inside information but given the faraway geographical location, it probably wouldn't be easy to track down anyone – especially since most only seem credited on a few older titles. How would one even find CEO Santosh Pillai, director Pramod Sahoo, lead artist Nirupam Borboruah, level designer Fani Kiran, interface designer Shivashankar Pujari, QA manager Kumar Jayapal, or game designer Pascal Luban?

Wait a minute, Pascal Luban? That's a French name! And didn't he work on Alone in the Dark and Splinter Cell? Why yes, yes he did, and in fact, he has his own detailed website. Though interestingly, while he lists Sony as a client and numerous other games he freelanced on, Chandragupta is conspicuous by its absence. Still, Luban was an easily contactable window into how Chandragupta came about. So many questions to ask... Did he relocate to India for the development? Was he based in New Delhi, the corporate headquarters for Sony India, or in the city of Hyderabad, where Immersive Games operated two subsidiary studios? What sort of local, on-the-ground research did he do to help with the design? How immersed in Indian history and culture and folklore and food did he become? Does he prefer Mughlai, or is he more of a Sambhar kind of games designer?

We immediately emailed Luban, describing our intentions and linking to the MobyGames page on Chandragupta. His reply was swift, "MobyGames is highly inaccurate." But he was happy to chat and kindly answered every email, adding, "I worked remotely for the entire project, but the management team was in the UK. I never went to India. The game was developed by Immersive Games, a company that had a studio in India, but the executives were in England. Send questions, I only ask you add my website when you introduce me." Just to be certain, we asked what his remote work actually involved. Luban stated: "I wrote the entire design, but the implementation was catastrophic."

It may not have been the South Asian odyssey we first imagined, but the development of this sounds like it had an interesting story. How did Luban get involved in such a project? "I work as a freelancer," he explained, elaborating that "many of my clients find me either on LinkedIn or searching the net. I was contacted by people from Immersive who found me that way. Once on the project, I worked as game designer, but I did not do the level design. I followed the development until release. I don't recall exactly how many months, but I think it was around 12 to 14 months."

Given how the game's French designer, its UK management, and Indian development team were each working remotely in different countries, it doesn't sound conducive to an easy project. What was the situation with Immersive Games, and were its studios in India a form of outsourcing? Was Chandragupta meant exclusively for the Indian market, or, as hinted by the PEGI rating, was it always meant to have a European release?

"Their headquarters were in the UK, and their studio was in India," says Luban. "Their strategy was to keep the high-value work in Europe and lower production costs by using manpower in India. The project was tailored for the Indian market but because it had a PSP version, they hoped to sell copies outside India to PSP owners who had little new games to buy."

What everyone really wants to know, though, is why was the project "catastrophic"? "They underestimated the importance of level design, which was not done by me," explains Luban, keen to distance himself. "As a result, it was done by designers lacking experience. I did reviews of the level design, but it was not enough to correct its flaws."

MobyGames lists only one level designer, Fani Kiran, though, as Luban pointed out earlier, the listings are not always accurate, and we may never know if any other hands were involved in the design. Sadly Luban is correct, and, objectively speaking, Chandragupta is not a good game. It has some clever ideas – for example, when swinging on a pole to reach a higher platform, your character's shadow-blur changes colour from blue to green to signify the maximum arc. It's a nice visual cue to aid jumping. Unfortunately, the first time you experience this, you need to leap from 19 separate poles, one to another, above a bottomless pit while arrow cannons fire from every direction, and one slip means instant death, and there are no checkpoints. (By the way, this is still the first level.)

It has brain-teasers to earn points, but these are frustrating to solve (slide puzzles, memorisation, nothing fun). There are bosses, but these just take the form of regular enemies, albeit with very long health bars, who call in waves of the regular guys to slow you down. The RPG system to buy new swords, arrow types, and bows to power yourself up seems ingenious at first; points are your currency, and your score can be increased by defeating enemies or collecting coins. Then you realise that nothing ever grants you quite enough, locking away the good equipment and making the game more difficult, which in turn makes it difficult to buy good equipment which would help with improving your score.

None of this, though, touches upon how insane the actual stage layouts are. Luban is being polite when he says they have flaws – some areas are so bizarre they almost transcend bad to become good. Well, maybe not good, but definitely intriguing in a weird kind of way.

To give one example: during the prison escape level, which starts off in some caves, you navigate up and down platforms and ropes through a labyrinthine tunnel network of guards. Eventually, you reach an impossibly large chasm with a rope leading down. Following this for a considerable distance, down various other ropes, eventually leads to a mysterious instant-death point, where your character, for no discernable reason, slips off a rope and dies. The layout of this section encourages you to retry it, conveying the feeling that the fall was due to clipping a wall or getting hit by an arrow cannon. This path is a lie - it can never be passed. The true path to the level's end is to attempt leaping that impossible chasm from earlier where as if by a miracle, your character will fly through the air and grasp the end of an almost invisible platform on the other side.

What's mesmerizing, though, is that Chandragupta has several anomalies like this, seemingly intended just to mess with your mind. What purpose do they serve? Why would artists and programmers expend time on such detailed things, which only frustrate, and then QA not curtail them? We asked Luban if he recalled this specific cave example. "Nope."

Ultimately the best aspect of Chandragupta is its cultural heritage and unique atmosphere, rather than its mechanics or the sensation of playing. If it used a generic fantasy setting, was made in Scotland (game dev is common there), and was titled Elf Warriors 2: Arrow Boogaloo, probably no one would care. Maybe it would get a footnote on a page covering bad Prince of Persia clones. But the setting, cinemas, dialogue, music, background motifs, character clothing – these all leave a lingering impression. These are the only reasons to play through it today. So we asked Luban, to what extent was he required to integrate themes of Indian culture and history? Did he consider an Indian target audience when conceptualising ideas?

"Yes," he confirms. "That was mandatory because it was viewed as the only way to drive parents to buy the game for their children. We also added a few brain puzzles in the game to give it an educational veneer. Through this game, I discovered the richness of Indian history. [Such a rich culture] should be used by designers as a source of inspiration. Western designers tend to build game worlds based only on European medieval history, but there is so much to explore." We could not agree with Luban more on this point. In fact, we point him to Time Extension's article which examines why Japanese developers also seem obsessed with European historical tropes.

Given how international games have become, we hope to see more titles which explore real-life myths, legends, and histories outside of our own. Is there some far-off region which you feel has a particularly fascinating indigenous culture that would be perfect for a video game? Post in the comments and let us know.