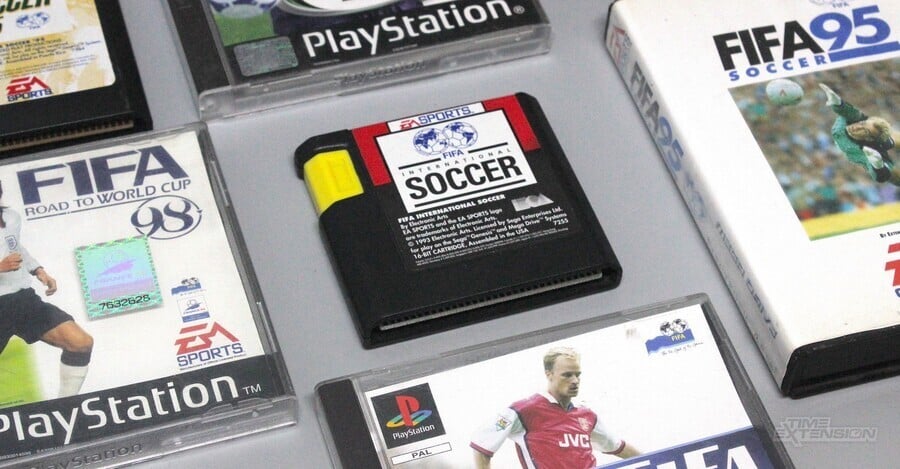

2023 is a milestone year for the FIFA series, marking the 30th anniversary of the original title, FIFA International Soccer for the Sega Mega Drive/Genesis. So we felt it was worth taking a trip down memory lane to look back at how the iconic footballing franchise came to be.

Originally released back in December 1993, FIFA International Soccer was developed by a small team at EA Canada in the Vancouver suburb of Burnaby, with support from members of EA UK who were based in Guildford. It was designed to be an authentic simulation of the popular sport in line with the company's other titles (like NHL Hockey and John Madden Football) and eventually kickstarted a phenomenally successful franchise that has sold over 325 million copies worldwide and became one of the best-selling video game series of all time.

This year sees EA officially ditching the FIFA branding to strike out on its own, but it's clear the legacy of FIFA won't easily be forgotten. So here at Time Extension, we've spent the last few months tracking down and interviewing members of the original FIFA team to find out more about its origins.

Early Demos In The UK

First things first, though, we should probably acknowledge that, while FIFA would eventually go on to be developed primarily at EA Canada, the origins of the project actually owe a large debt of gratitude to the determination of the EA UK office, who did its best to convince its parent company to make a video game based on the sport.

At the time, EA UK was only a small regional branch that was responsible for supporting external development and testing and marketing North American products in Europe. It wasn't necessarily set up for internal development.

However various members of its marketing and production teams believed that an authentic football experience for the Sega Mega Drive could be a mega-hit for the company and tried to convince their bosses of the idea; among them was the EA marketing manager Neil Thewarapperuma.

"Essentially, we were taking a US product and putting it out in Europe," says Thewarapperuma. "We were basically just reconfiguring everything, translating everything, and doing new packaging and stuff like that. And then a lot of those games that were successful were sports games. So Madden was huge. We did EA Hockey because we didn’t have the NHL license. And they were pretty successful because they were really good games. [...] But I wanted to do a football game, so I wrote a WhyEA, [which] is generally speaking a technical document where you basically justify why EA should produce a product. I don’t know if anyone was doing that in marketing at the time. No one had done it in Europe certainly."

Thewarapperuma submitted the document, but nothing seemed to come of his suggestion. Then, one year later in 1992, another member of EA UK named Matthew Webster, raised the idea again, this time putting together a deeper design document for a potential title called EA Soccer.

Webster had joined EA UK two years prior in 1990, but game development hadn't been his first choice of career. Instead, he had initially dreamed of entering the RAF. But after spending three days on a Royal Air Force base to obtain his flying scholarship, he quickly realized that "military life wasn't for him" and that he needed to find a new career to work towards. This led him to apply for a job at EA.

"I went for an interview there and got a job in customer service," Webster tells us. "But I really wanted to get into game development because I loved games at the time. So I managed to get a job as an assistant producer and I was working with a producer called John Roberts and I was his sort of assistant. One of the first things I did when I was in customer service was I QA’d what was EA Hockey at the time because EA didn’t have the rights to the NHL outside of North America. It was a really awesome game on the Mega Drive. So I was like we should make a football game. So I put together a design document for EA Soccer, or EA Football as it was also called."

Because EA UK didn't have a proper internal development team, Webster needed to find an external development partner in order to help the subsidiary build prototypes. It was at this point he remembered a couple of developers based in Widnes named Jules Burt and Jon Law who had recently been pitching a volleyball demo to EA. The pair didn't have any official Sega development tools but had managed to secure a makeshift dev kit from a German salesman at a trade show. This was a wire-wrapped board that connected to the top of the Sega Mega Drive and interfaced with a Commodore Amiga.

One of the key things we thought we were pitching to EA was a volleyball game. [...] We were trying to do something cartoony with a bit of an arcade feel.

Burt recalls, "One of the key things we thought we were pitching to EA was a volleyball game. [...] We were trying to do something cartoony with a bit of an arcade feel. You know, super smooth and all that. So we had a few meetings at the time with EA and they had come up a couple of times to our house/studio. I remember it was about the third visit, Matt had come up again, but he had brought with him his boss John, and we were like, ‘Oh, what’s this other guy doing here?’ And they came up with this bad news of, ‘Sorry, we’re not going to sign your beach volleyball game, but we’re just wondering if you guys would be interested in doing football [instead].'"

The pair was inevitably disappointed about having to ditch all the hard work they had done on the volleyball game. But, nevertheless, they pressed on with EA's football idea and over the next three months managed to whip up three different prototypes of how the game could look. The first two demos featured a side-on-parallax view and a Madden-style perspective (with the player running in and out of the camera), while the third had an isometric look that came about thanks to an unlikely bit of input from Burt's dad.

"My Dad kept popping in while we were working," remembers Burt. "And he was like, ‘Why can’t you make it look more like TV?’ So, at one point, for some reason, we thought, ‘Let’s try an isometric pitch.’ And so we did. Jon laid it out; I got the scrolling working again and we got some action going and we were like, ‘Hey, this is really cool actually.’"

The pair presented the three different perspectives to EA and it was the isometric look that impressed the publisher the most, with Webster seeing it as a way to differentiate the game from the top-down football titles at the time like Kick Off and Sensible Soccer.

"We saw that isometric view and we were like, ‘Well, that’s it!'" says Webster. "We were like 'That’s different, that’s fresh.’"

A Fresh Start In Canada

Based on this feedback, everything was falling into place for Burt and Law to take the project further, but then, all of a sudden, there was a decision higher up within EA to move the project to EA Canada — a new EA studio created from the 1991 acquisition of Distinctive Software (DSI). For Burt and Law, this was a difficult pill to swallow, to see the project that they had been working so hard on be shifted somewhere else. But both men have since admitted that the decision was for the best.

As Burt explains, "Had we moved forward with it, we would have struggled to create all the other real content like the audio or any of the surrounding screens. There just wouldn’t have been enough bandwidth with the two of us, and we didn’t necessarily have a good connection of other people we could tap into."

To soften the blow, EA offered Jon Law and Jules Burt a job at the UK branch, where they later worked on Rugby World Cup '95 for the Sega Mega Drive. Webster, meanwhile, stayed on the football project as an associate producer, keeping in close contact with the team at EA Canada over the phone (before moving to Canada temporarily to be in the same room).

"I think EA Canada had been around for like a year or so [at that point] because we’d bought DSI," Webster tells us. "And they were going through their own integration challenges, I think, with the team up in San Francisco. So [the UK studio leader at the time] said, ‘If you’re serious about this soccer game, why not place it there?’ So we got a prototype over to them and said, 'This is the view we're going for'."

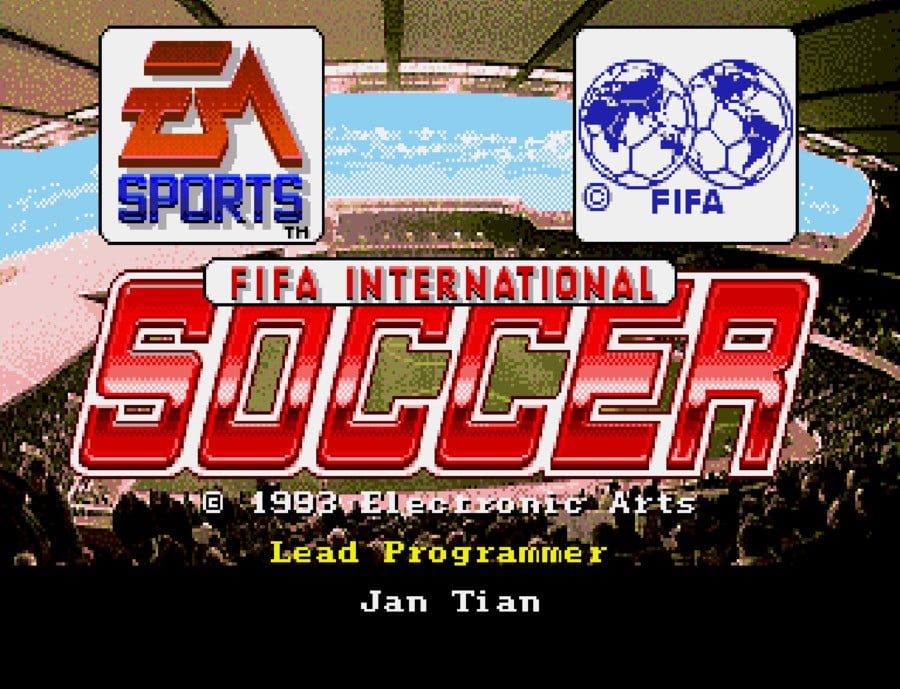

EA Canada began work on the rebooted EA Soccer at the end of 1992, with the initial core team comprising the producer Bruce McMillan, the development director Joe Della-Savia, and the engineers Jan Tian and Brian Plank. Plank, at the time, was an audio programmer at the studio, whereas Tian had just led the development of another sports title named 4D Sports Tennis.

Plank remembers how he got assigned to the project: "I got tapped on the shoulder I think in December and they said, ‘We’re thinking of doing a soccer game. Would you drop your audio stuff to do that?’ And I basically said, ‘Yeah, that sounds cool!’ I already knew Jan Tian at the time, but I didn’t know him well. He originally did a tennis game and then got pinged to work on this. So Jan and myself were the first two programmers to work on FIFA. And like I said, I think we got tapped around December. We didn’t earnestly get going though until the beginning of January."

"I was totally burned out by the tennis," admits Tian. "I was like, ‘I don’t want to make a sports game, I want to take a break.’ But my producer, Bruce — he was a great soccer player – he was like, ‘You should do it! You’re the best person that we have. You should work on it.’ So eventually I said, 'Yeah'"

To begin with, the team took a long, hard look at some of the other games on the market, while Tian created an AI testbed on PC to refine core features like passing, positioning, and dribbling.

"I just wanted to prove the gameplay," says Tian. "Not the animation or the graphics. So, on my PC, I drew a field that was square lines and from that, I just created two openings for the goal lines and my player was just a stick and the ball was a white dot, right? I just wanted to be able to run with the ball and see that the player could kick it and chase it. I also wanted to be able to pass to teammates easily."

Jan was a really strong [technical] person. He had an aspiration. His love was football. So it was natural for him to be on the project, whereas Brian had no idea about football at all. Which was kind of fun.

"Jan was a really strong [technical] person," says McMillan. "He had an aspiration. His love was football. So it was natural for him to be on the project, whereas Brian had no idea about football at all. Which was kind of fun. What was really interesting, though, is what we did first was we had the discipline of just having two characters on the screen passing the ball back and forth. That’s how the game started. It didn’t matter about cameras. It didn’t matter about whatever. We just made that and really, really refined it."

"Jan was the guy who could do the gameplay and the soccer and I was kind of doing everything else," explains Plank. "Probably the best way to describe what we were doing is to paint you a picture. We sat in a little cube area and our backs were facing one another. So Jan was literally right behind me and I was on the other side. So we could decide when we wanted to communicate and turn around or we could decide when to have our heads down and work. We would go back and forth and we were playing the game, so as Jan would make changes we would decide if we liked it or not."

Development Continues

According to Plank, this initial testbed for EA Soccer was written in C++, a fairly fast, high-level programming language. The idea was to eventually try to get the code up and running on a Sega Mega Drive development kit. However, at some point, the team realized the available compilers (which were used to translate the code into the console's 68K machine language) weren't exactly good enough and that a more hands-on approach was necessary.

So literally for two days straight, it was like heads down, don’t mess with me, don’t bug me, don’t distract me, and I took all of the working code that Jan had written and basically converted it to C and got it working on a [Genesis].

"I became a human C++ to C compiler," says Plank. "So literally for two days straight, it was like heads down, don’t mess with me, don’t bug me, don’t distract me, and I took all of the working code that Jan had written and basically converted it to C and got it working on a [Genesis]. So kind of like overnight, we went from having a testbed to a game running on a Genesis. And then we did a hard switch. I basically said to Jan, ‘You’ve got to start doing it all in C because that’s our path forward now.”

From here, the game progressed fairly quickly, with several artists and sound people getting involved to help flesh out the experience. Similar to Burt and Law's earlier prototype for the game, EA Canada's version of the title took advantage of an isometric perspective to display the action on the field, with Plank attributing this design choice to his love of classic '80s arcade games like Zaxxon.

The chief concern among the developers while working on the title was authenticity. So the team made a habit of watching whatever footage they could get their hands on and breaking down everything from how the players moved to why they would make certain decisions on the pitch.

Bruce McMillan recalls, "[Our librarian at EA] Linda grabbed all the footage she could get from around the world to try and grab what football is. So rather than watching TV at night while we were eating dinner, we’d all watch footage [of football matches]. We’d be watching like, ‘Why did he do this?’ ‘Why did he do that? ‘Why is the defender suddenly kicking the ball out on the side?’ It's positioning, right? You kick it out and you reposition the whole team."

George Ashcroft, the lead artist on the game adds, "[We were watching a lot of] VHS videos at the time. Anything from Greatest Goals to even blooper stuff. We had a few tapes that somebody had bought somewhere and we were just going through them, so they were well-worn, for sure. Then, you know, we had some people who had some knowledge of player stuff too. So we were just using those guys as a resource. [As for the animated scoreboards we did], that probably came from hockey. The NHL had some scoreboard stuff, I guess. It was basically just a place in the game to make it feel more impactful when you are scoring a goal. Like how do we make this feel bigger?"

[We were watching a lot of] VHS videos at the time. Anything from Greatest Goals to even blooper stuff. We had a few tapes that somebody had bought somewhere and we were just going through them, so they were well-worn, for sure.

"I was working with Jan on what became the formation editor," says Webster. "So he had come up with this system that had broken the pitch down into loads of squares and you would place a ball in each square and for each formation – and this is what I ended up doing a lot of work on – you would plot where you wanted the players to be. So when the ball moved, the rudimentary AI would try and get the players into particular positions and or particular formations. So I was doing a bunch of that."

As the game grew and took shape, the staff at EA Canada became more and more confident in the project, not least because of the enthusiastic feedback from the testing teams in both the UK and Canada. Neil Thewarapperuma, who is credited as the game's product manager, remembers loading up the latest builds in the UK office and being blown away at the progress.

“The work that the EA Canada people did was fucking insane," claims Thewarapperuma. "Because every time we got a build, it was like ‘Holy shit!’ And when they put crowd sounds in, we were like, ‘Are you fucking serious?’ No one else had done this before. It was like, 'How the fuck?'"

The team was putting everything it could into making the title the best it could be. But for one employee, in particular, this became a source of problems. As the lead programmer, Jan Tian, admits, he became a workaholic during this period and would constantly find himself visiting the studio out of hours to tweak the code for the game's AI and try to get things perfect. This often came at the expense of both his health and home life.

Bruce picked up the phone, and on the other end was my son who was only like 8 or something at the time and he said, ‘Can you make Dad come home please?’ It just brings tears to my eyes

Jan remembers, "One Sunday night I went back to the studio to try out this new idea and Bruce came in and said, ‘Jan, you’re still here?' So he sat down and started chatting with me. Then the phone rang. Bruce picked up the phone, and on the other end was my son who was only like 8 or something at the time and he said, ‘Can you make Dad come home please?’ It just brings tears to my eyes, because he hadn’t seen me and I hadn’t seen him for like 2 or 3 months. That was so hard on family life. I don’t know how I did that. I was suffering from anxiety attacks because of the stress and overwork. I sent myself to the hospital three times."

"We used to have to lock Jan’s keyboard," McMillan claims. "Jan [would say], ‘I’m going to change the whole play model tonight.’ And I would say, ‘No, you’re not. Lock his keyboard! You have to go home and sleep.’ Jan is a brilliant guy. He’s really, really brilliant, but he would work through the night if we didn’t send him home."

Plank adds, "Jan is an extremely hard worker. But I always say, ‘You can work hard, but remember it’s a marathon, not a sprint.’ So I think Jan to some degree treated it as a sprint and I treated it as a marathon. [...] I don’t think is an exaggeration to say but I didn’t know whether Jan would make it through the title. So my job and the way I sort of viewed it – though nobody told me to do this – was I would get this product out the door no matter what. Like, I will ensure that this product gets out the door and that it's good. So I always thought if he has a problem, can I take over?"

The FIFA License

Something that may surprise you about FIFA is that for much of its development, it didn't actually have the FIFA name attached to it, with the game instead being referred to internally as EA Soccer. This all changed, though, when a group of individuals within the UK branch managed to get in touch with the company ISL (International Sports and Leisure) through a Welsh football referee and FIFA representative named Keith Cooper. ISL was the organization responsible at the time for the licensing of the FIFA brand.

"I didn’t know how to get in touch with FIFA so I literally just rang them up in Switzerland and said, ‘Can I speak to Keith Cooper?’" Webster recalls. "And they put me through and I said, ‘Look, we’re interested in making a video game with FIFA, can you point us in the direction of somebody who does licensing?’ And that’s when we got hooked up with ISL, who were at the time their licensing arm."

"I think it was June of 1993," says Tom Stone, EA’s former vice president of European marketing. "We met with a guy called Ross Berlin and we actually very quickly came to a deal. We shook hands over dinner and said, ‘Okay, we’ll become your worldwide official licensee’. It was a four-year deal. I think it was 1993 through 1997. What we realized was in order to make a point of difference, a point of distinction between FIFA and all the other football games, we needed to have those real teams, real names, apparel, stadia, etc."

The FIFA name gave EA an edge over its competition, but as the company soon discovered it didn't provide everything it was after. Most notably, the license didn't include official player names or likenesses.

"I think enough time has passed to say it’s not the license we wanted," admits Thewarapperuma. "It really isn’t. But it became synonymous with the game and it later became synonymous with world football.

"For the first game, we didn’t really know what to do with players," adds Webster. "It was sort of an unnecessary burden to go figuring that out whilst we were actually [working on it]."

Inside EA, a database was put together and an email went around the company asking people to come forward to volunteer their names. Some agreed to play for their own country, while others tried to secure a place on their favourite teams.

"I gave myself the best player, the best jersey, for the best team, which was the Brazilian national team," Tian admits. "But my manager said, ‘Hm, yeah, you don’t want to have an Asian name on the star player of the Brazilian team.’ So he just added an ‘O’ to my name, so instead of Jan Tian it was Janco Tianno."

Plank elaborates, "It was kind of like fake names intermixed with people in the office and/or their partners. It was very random. I had control not only over the names, but I had control over all the attributes of all the players and all the teams and that sort of stuff. That’s how my player became one of the most powerful players in the game. Obviously, because I own the database, right?"

I said, ‘I’m going to bet my whole job, my whole career, that if we call it US Soccer, it’ll be a failure. We have to call it FIFA. We have to be around the world as FIFA.'

Everything seemed to be shaping up nicely in anticipation of the release, but toward the end of development, EA's North American marketing department threw a spanner in the works, suggesting that the company drop the FIFA license in America and call the game "US Soccer" instead to try to market more directly to Americans.

McMillan recalls, "I sat down with a founder of EA, Bing Gordon, in our boardroom in Vancouver and I said, ‘I’m going to bet my whole job, my whole career, that if we call it US Soccer, it’ll be a failure. We have to call it FIFA. We have to be around the world as FIFA. That is the name it has to be.’ I was almost emotional, I tell you. I was just so determined. I said, ‘This is the way it has to be. It has to be a unified FIFA product around the world and we have to ship that product.’"

Marc Aubanel, an assistant producer who also worked on the first FIFA game, supports this account. He tells Time Extension, "The US hated it. They really wanted it to be called US Soccer, which we looked at it and we were like, ‘You’re fucking crazy. You’ll sell nothing."

According to Webster, the plan almost came to fruition, with the idea only being scuppered after Mark Lewis, the Vice President of Electronic Arts Europe, reminded the US marketing division that it wouldn't be able to give the UK its unsold stock if the game was called something else in another region. Seeing sense, the US team eventually relented, letting the two parties in Canada and the UK breathe a celebratory sigh of relief.

Making A Phenomenon

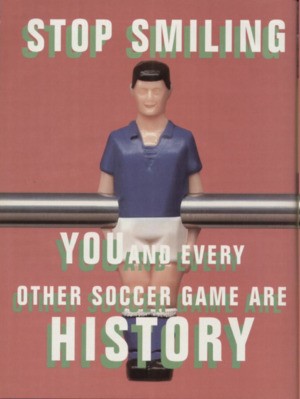

Ahead of FIFA's launch, the forecasts from the sales team within the UK were incredibly positive, so the company began a huge marketing push. This led to one of EA's first-ever television adverts in Europe, countless magazine ads, and a bunch of positive press.

"We had a brilliant press team who were really good at their job," Thewarapperuma tells Time Extension. "They would take out prototypes and it would blow people’s minds. I’ve still got the quotes. Before FIFA, you had Sensible Soccer, Kick Off, and all these games that all had these top-down views. And, in fact, our first teaser ad for FIFA was — and this is not something British companies do — it was sort of attacking the opposition."

"It was sort of coming out of nowhere," says Webster. "Simon Jeffery, who is the guy who used to run the PR team, [...] was like, ‘The previews are going crazy for this.’ Then we heard word that Virgin was moving the release of Sensible Soccer to get out of the way because they expected this was going to review really high."

The hype continued to build in the months leading up to the game's hotly-anticipated launch, with EA throwing a special celebration on September 8th, 1993 at Wembley Stadium ahead of a World Cup qualifier between England and Poland.

"I can’t remember who did that," says Thewarapperuma. "It might have been First Artist. So we worked with a promotional company called First Artist and they were really good. They definitely did the FIFA ’95 launch, which I think was at Arsenal. But the England-Poland match worked so well. I don’t know whose idea it was, but we had a dinner or something, and we had a presentation of the game, then we sat them down in […] a specific part of the stadium where you look down on an isometric viewpoint so it looks exactly like the game."

"We had a bunch of screens up in the room," adds Stone. "We’d invited all of the FIFA officials to come and witness the launch of this game that bore their name and I met them all and shook hands and a guy said, ‘Oh look, is the football started?’ I said, ‘No, that’s our game!’ On one level, that’s sort of how naïve they were, but on the other hand, it was the first time a football game had been presented as that realistic 45-degree isometric view.”

FIFA International Soccer launched on December 3rd, 1993, and got great reviews from critics upon its release. Mean Machines Sega, the UK's No.1 Sega magazine, praised the "utterly amazing" animation, "superlative presentation", and "easy to pick up and play" gameplay. It gave the title 94% with the magazine concluding:

"Anyone who plays FIFA Soccer must concede that this IS Football. [It's] in the Mega Drive’s sporting elite."

The all-format magazine Computer & Video Games, meanwhile, awarded the title 92%, with the reviewer Paul Rand summing up the game as follows:

"Everything combines to make Electronic Arts FIFA Soccer a stunning footy game. Lurvely flowing graphics with brilliantly sized sprites and a different to the norm perspective. The sound FX are as realistic as you’re likely to get without actually getting up off your bum and walking down to your nearest footy ground. And of course the delightful gameplay is a joy to be a part of."

For the team back in Canada, the positive press was a validation of all the hard work that it had put in to make an authentic football experience, but it also resulted in some unexpected problems for EA as the game started to outsell even if it's most generous estimates.

After the Sega Mega Drive, FIFA International Soccer was ported to the 3DO, Commodore Amiga, MS-DOS, Game Boy, Game Gear, Sega CD, Sega Master System, and Super Nintendo. The following year it also went on to have its first sequel FIFA 95, which added club teams. Year by year, the series continued growing more successful and more advanced, leading up to the more recent versions of the game that younger readers will likely be more familiar with.

In May 2022, EA announced that it was officially ditching the FIFA brand and moving forward as EA Sports FC — a decision that was arrived at due to FIFA demanding more than double what it was currently receiving from the developer for the latest license renewal. FIFA's president Gianni Infantino has since tried to assure football fans that the FIFA series will continue without EA's involvement, but many are skeptical about their odds of success.

To close out our conversations, we asked various members of the development what they make of the news (and the potential end of the series). Here's what they had to say:

"For me, as a creator of FIFA, I’m disappointed that they are not still working together," says McMillan. "Because it’s 30 years in, right? It’s kind of crazy. […] It is a weird situation. We’ll see how it goes. Now, EA is going to be successful. EA is an outstanding company, so it’s not going to go sideways. I hope FIFA finds somebody that will help them with this next thing, but it really is an expensive business to be in right now."

Matt Webster meanwhile adds, "Personally the video game doesn’t need those four letters. It just doesn’t need it. And I think, you know, when I look at what the FIFA organization has said subsequently, it’s obvious that they don’t quite understand the creativity and complexity as well as the power of video games and so are somewhat oblivious to the impact. It’s going to be business as usual for Electronic Arts and the team creating EA Sports FC and the FIFA organization has lost perhaps one of the primary positive things the rest of the world thinks about them. So, it should have happened years ago..."