If you live outside of North America and Japan, you might not have heard of the BattleTech Centers – but they were amazing places, years ahead of their time.

There were around 26 of them at one point, dotted across the United States, Canada and Japan. They were like Disney theme parks for gamers, offering simulated 3D mech battles at a time when 16-bit consoles were only just emerging. Players sat inside a realistic mech cockpit – with multiple monitors, joysticks, pedals and a myriad of switches and flashing lights – going head-to-head with other players in the same room, or even fighting mech pilots on the other side of the world – despite the fact that many people hadn't even heard of "the World Wide Web" at this point, let alone had internet access at home.

These futuristic battle arenas were the brainchild of Jordan Weisman, serial entrepreneur, theme-park obsessive and creator of franchises such as Shadowrun, Crimson Skies and, naturally, BattleTech – which began as a board game but soon evolved into a tabletop RPG, novels and the MechWarrior series of video games. And it all began when he attended the US Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York, in 1979.

"They had just finished this $50 million bridge simulator that was built for ships’ pilots," he tells Time Extension. When a ship approaches a harbour, a pilot who knows the local waters is sent out on a boat to meet the ship and take over the controls to guide it safely into port. The simulator was built to train pilots without the risk of novices accidentally bulldozing a 1,000-ton ship through the local dockyard.

And with the naivete of a 18-year-old, I was like, it doesn't need to cost $50 million. I can just do that with my Apple IIs at home

"I just looked at that and said, 'Well, shit, that's the future of entertainment right there'," says Weisman. "And with the naivete of a 18-year-old, I was like, it doesn't need to cost $50 million. I can just do that with my Apple IIs at home." So he quit the academy, went home, and hardwired two Apple II computers together in an attempt to build his own bridge simulator – but Weisman’s would simulate the bridge of a starship. "Which is how I destroyed my Apple II," he laments. "Anyway, we quickly figured out that it was going to be harder than we thought, but I was still convinced that some form of networked microcomputers was going to be the way to create these kinds of simulations."

His idea was that, just like in Star Trek, different people would take up different positions on the bridge, with the aim of working together to beat the simulation. Convinced it would work, Weisman came up with some game designs and concept drawings and headed out to raise some venture capital funding. But it didn’t go well.

"Everybody I met looked at me and said, 'Oh, you're a college dropout who has never made anything'," recalls Weisman. His plan to build a video game where people would buy tickets like going to the cinema simply baffled investors. So Weisman put the bridge simulator on the back burner and tried something else. "I said, alright, well, why don't I take these ideas, or something similar to these ideas, and use them in the traditional tabletop RPG world." The aim was to use the profits from selling tabletop RPGs to make the starship simulator a reality.

I thought, well, it'd be better if we created cool intellectual property that we owned. So I made BattleTech

Weisman formed FASA Corporation in 1980 with L. Ross Babcock III, a friend from the academy. FASA stood for ‘Freedonian Aeronautics and Space Administration’, a reference to the fictional country of Freedonia in the Marx Brothers' movie Duck Soup. FASA began by creating expansions for existing RPGs, but the company soon secured a license from Paramount to create a game based on Star Trek. "I took the designs that I had built for all the interactive bridge simulators and applied them to a pen-to-paper RPG," says Weisman.

The Star Trek line did very well indeed. "Then I realised we were creating all this very cool intellectual property that Paramount owned," says Weisman. "And I thought, well, it'd be better if we created cool intellectual property that we owned. So I made BattleTech."

Weisman had run into someone at a trade show who was importing Japanese mecha figures related to the shows Super Dimension Fortress Macross and Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross – the same two series that would be combined to create the Robotech franchise, coincidentally. The figures were excess inventory that was being dumped on the American market after the popularity of the shows waned in Japan. "I just thought the imagery was incredibly cool," says Weisman. "So I worked out a deal where we would buy a huge number of these miniatures, these small plastic kits, and I would use them as playing pieces." FASA then created an original story based around the Macross/Southern Cross mechs, and the BattleTech universe was born.

So I worked out a deal where we would buy a huge number of these miniatures, these small plastic kits, and I would use them as playing pieces

The resulting BattleTech board game sold incredibly well on its debut in 1984 (originally, it was called Battledroids, but the name was changed after Lucasfilm complained), and it was soon followed by the MechWarrior tabletop RPG, also set in the BattleTech universe. "It really just catapulted FASA quite significantly," says Weisman. "And we said, alright, we're making some money now, let's go back and try to build the original vision, go and build these location-based entertainment centres."

Weisman started a new company called ESP (Environmental Simulations Project), and to create the hardware, ESP partnered with Incredible Technologies, the firm which would go on to release the enduringly popular Golden Tee Golf in 1989. By this point, Weisman had pivoted away from the idea of a starship bridge simulator for two reasons. One was the surging popularity of BattleTech; it made sense to capitalise on its success by making a game where you piloted a mech rather than a starship. The second was the potential difficulty in finding full crews to join a bridge simulator.

Weisman points out that if there were five crew positions on the starship bridge, players might not necessarily be able to find four friends to join them, leading to either empty spots (and thus lost revenue) or a less-enjoyable experience of formulating strategies with strangers.

We started out with the misconception that it was going to cost about $300k. And in reality, it cost about $3 million

The project kicked off in earnest in 1987. ESP and Incredible used custom-built hardware to create advanced 3D simulators which could be networked together, and the firms showed them off for the first time at GenCon in 1988, the largest tabletop convention in North America. But they badly needed extra funding. "We were desperate for money, because this thing ended up costing ten times what we thought," says Weisman. "We started out with the misconception that it was going to cost about $300k. And in reality, it cost about $3 million." To plug the funding gap, the firms took on several side contracts, such as making laser tag venues and working with Jeep to create driving simulators for the Detroit Auto Show. "We built Jeep cockpits using the actual Jeep steering and gearshifts and everything, so that was a fun project," says Weisman.

When it came to the design of the BattleTech 'pods', as the simulators were called, Weisman says he was influenced by a review of Star Wars, which said there was so much going on in every frame of the movie that you simply couldn’t track it all. "My premise for the cockpits was I wanted to do that same thing," he says. "I wanted sensory overload and information overload, where part of the challenge was coming to understand what piece of information you need to focus on and when."

In addition to the main screen, which showed the view from the front of the mech, the player had a secondary radar screen, as well as various lights and indicators depicting the mech’s weapon systems, armour and so on. "So you just had a tonne of stuff coming at you," says Weisman. The mech was controlled using a left and right joystick as well as foot pedals, a set-up that would later be copied by Capcom for the Steel Battalion controller in 2002. "That was very much a direct derivative from what we did in the BattleTech Centers," notes Weisman.

I wanted sensory overload and information overload, where part of the challenge was coming to understand what piece of information you need to focus on and when

The core of the first-generation pods was an Amiga computer with slots for additional graphics and memory cards. Weisman says they built a custom image generator based on a Texas Instruments chip that was normally used for adding titles to TV shows, rotating and scaling things like the logo for a football team. While the TI chip generated the images on the main screen, the Amiga handled the radar display. The sprites for the game were all pre-rendered, then squeezed and twisted by the custom graphics card to give the illusion of 3D. "But that meant we needed a lot of memory to be able to hold all of the pre-rendered sprites," says Weisman. "So we built this memory card that was almost half a metre square. It was a giant 16 megabytes!"

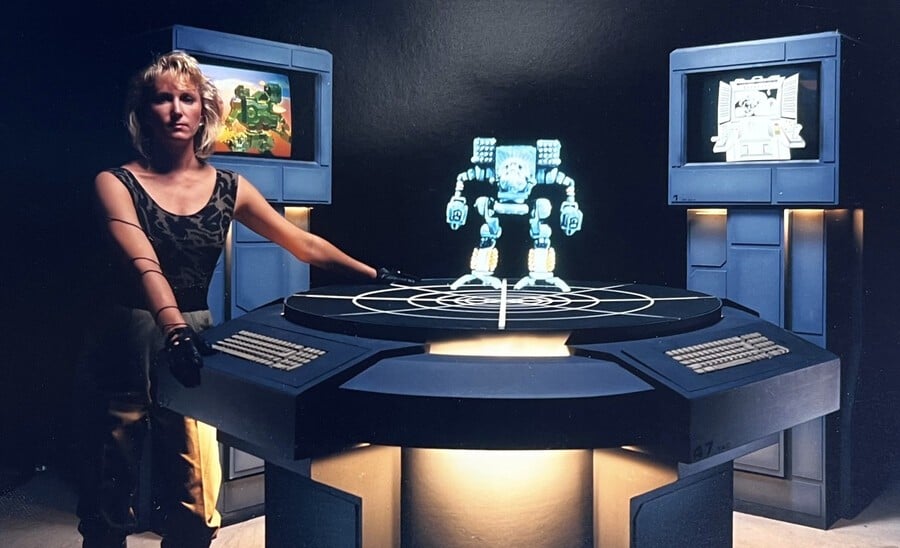

However, the BattleTech Centers were just as much about theatre as graphical oomph. "I’m a huge Disney fan, and my wife and I have been going to the park since our second date," says Weisman. "We fill up notebooks with observations." One of those observations was how Disney theme parks use a 'pre-show' to build anticipation ahead of a ride, and Weisman copied this for the BattleTech Centers, adding a wall of monitors to broadcast in-game footage and making sure the décor was suitably 31st-century. Before entering their cockpits, players were gathered together in a room for an exciting pre-ride briefing, where they were shown an instructional video set in the BattleTech universe.

Later versions of these briefing videos featured big-name Hollywood actors such as Jim Belushi, Judge Reinhold and 'Weird Al' Yankovic. Weisman remembers that Belushi turned up to play at the Chicago BattleTech Center one day, so he summoned up the guts to wander over and ask whether he would star in their new training video. "We had no money, but he was incredibly gracious and shot it with us." And Belushi wasn’t the only Hollywood star to become a fan of BattleTech; Kurt Russell was a regular attendee while he was shooting the movie Backdraft in Chicago. "He would literally just show up almost every day, and just get in line and buy his ticket and play," recalls Weisman. "And then a couple of times, he rented the whole place out for the cast and crew."

People would collect them in binders. Laser tag eventually grafted [onto] these same things, they realised the value of these printouts as well

The post-show was just as important as the pre-show. Weisman calls it the 'bus-crash phenomenon'. Normally you might not interact with the other passengers on a bus, but if the bus has an accident, even a very minor one, everyone starts talking. "When our adrenaline is high, we have a need to communicate," Weisman notes. At the end of their battle session, players would be gathered together to discuss what had happened, and each was given a printout showing their score and a rundown of what they’d done in the game: where they had travelled to, who they had attacked, and how. "People would collect them in binders," says Weisman. "Laser tag eventually grafted [onto] these same things, they realised the value of these printouts as well."

The first BattleTech Center in Chicago opened in 1990, and it was soon followed by one in Yokohama, then Tokyo, and further sites across the United States and Canada. Soon they began to be linked up via ISDN cables, allowing players to battle folks on the other side of the country, or even the other side of the world – something that Weisman thought people would go wild for. But they didn’t, at first. "We were like, 'Why aren't they getting excited?' And we realised, it’s because they don't know the people in Tokyo."

Fighting against an unknown foe was infinitely less exciting than battling your friend in the next pod, so the BattleTech team tried to inject some personality into the online head to heads. They added leaderboards, tracking the progress of players in centres across the globe, so players began to recognise the aces of the BattleTech world. In the early days of the internet, they even began posting videos of games and sharing written interviews and articles about rising stars. Essentially, the BattleTech Centers were doing eSports long before the phrase was even coined.

The eSports thing was something we pioneered in the early '90s when we started doing regional, local tournaments, and then national and international tournaments, and they were broadcast on television

"The eSports thing was something we pioneered in the early '90s when we started doing regional, local tournaments, and then national and international tournaments, and they were broadcast on television," says Weisman. "So it's been fascinating to watch eSports recreate that on a much larger scale, because people are doing it in the millions from their homes versus, for us, in tens of thousands from these dedicated centres. But it's very much the same kind of dynamics."

The BattleTech machines were overhauled multiple times as technology improved. The second-generation machines ditched the fake 3D for proper polygons, although they were flat and lacked any texturing. "You could argue that was a step forward or a step back," Weisman notes. "From a technology standpoint, definitely a step forward; from a visual presentation [standpoint], maybe half a step back." Eventually, fully textured polygons were introduced with the 'Tesla pods', a complete redesign of the cockpits that was introduced in the mid-'90s, by which point the Amiga had been dropped in favour of a PC.

Weisman was also convinced to upgrade the audio by one of his engineers, who rigged up a test where members of the public were invited to play on battle pods with stereo sound as well as on battle pods with upgraded five-channel surround sound. Weisman says that none of the testers mentioned the audio, but they all thought the graphics on the surround-sound pods were much improved. "They didn't interpret it as the sound was better, they just knew it was more immersive, and they attributed it to the graphics."

The premise is when you get into the cockpit, we transport you off into the world, and the cockpit then becomes any vehicle it needs to be in that world

In 1992, Tim Disney – Roy Disney’s grandson – bought a majority stake in the company, "which was great because we were scrounging for money constantly and really fighting to keep the lights on," says Weisman. That led to the Tesla cockpit redesign and a rebranding of the centres as Virtual Worlds. "I wrote all kinds of metafiction about the Virtual Geographic League and this whole history of travelling to other worlds and other dimensions," says Weisman. "The premise is when you get into the cockpit, we transport you off into the world, and the cockpit then becomes any vehicle it needs to be in that world." Another game was introduced, Red Planet, which saw players racing through the canals of Mars and starred Judge Reinhold and Joan Severance.

The company, by now called Virtual World Entertainment, was merged with FASA Interactive in 1996 to become Virtual World Entertainment Group (VWEG), and not long after that, Weisman decided to leave. "When we merged them together, the guy who was running FASA Interactive now kind of ran both," he says. "And he’s a good guy, but our styles weren’t meshing very well, and I wasn’t super happy." Weisman decided to go off and do something completely different, which is how he ended up making the Crimson Skies board game in 1998.

Microsoft ended up buying VWEG in 1999 but kept only the FASA Interactive arm and sold off Virtual World Entertainment to a group headed by former VWEG chief Jim Garbarini. By that point, the nature of the Virtual World locations had changed considerably, following a deal with the US arcade chain Dave & Buster’s. "We were doing less standalone centres and more kind of mini centres inside of David & Buster’s," recalls Weisman. "So instead of having 16 to 32 cockpits in a standalone centre, we would be doing eight to 16 cockpits inside of a Dave & Buster’s – with its own themed area, but nowhere near as immersive as our dedicated themed locations."

We did have some kind of area around the cockpits that was for socialisation, but it was less separated from the larger cacophony of Dave & Buster’s, so it didn't quite recapture that intimacy of the dedicated venues

Weisman thinks that the Virtual Worlds were diminished after this transition. "I think it lost a sense of its own community,” he says, citing in particular the loss of the Explorers Lounge, where pilots would gather before heading into a mission. "We did have some kind of area around the cockpits that was for socialisation, but it was less separated from the larger cacophony of Dave & Buster’s, so it didn't quite recapture that intimacy of the dedicated venues." The Dave & Buster’s deal saved a lot of money on staffing, rent and customer acquisition, notes Weisman, "so economically it made a lot of sense, but it definitely lost a little something."

And ultimately, it was the high cost of creating and running the BattleTech Centers that saw them eventually disappear. The original centres were designed to be as low-cost as possible and could be run by just one person at off-peak times. But with the rebrand to Virtual Worlds, the set-up became much more elaborate and significantly more expensive. The original BattleTech Center in Chicago cost around $750,000 to set up, but Weisman estimates that the later Virtual Worlds cost around one and a half to two times that amount, and each Tesla pod set them back well over $25,000 to produce.

"They were beautiful," he says of the Virtual World centres, "but they just didn't scale as well." Typically, each centre would see huge traffic in the opening year, but this reduced significantly as time wore on and the novelty factor wore off – which wasn’t so much of an issue with the early venues, which could still remain profitable with lower footfall, but it was disastrous for the later, more elaborate centres.

It's pretty funny and rewarding to go to GenCon, and there's still 20 cockpits set up, and they're running 24 hours a day

The BattleTech brand has survived despite the disappearance of its location-based offering. The tabletop game continues to thrive, and we've seen several video games based on both BattleTech and MechWarrior (the most recent being MechWarrior 5). As for the original immersive game, a dedicated BattleTech scene endures to this day. Several fan groups have bought and refurbished BattleTech pods, and tour them around conferences in the United States.

"It's pretty funny and rewarding to go to GenCon, and there's still 20 cockpits set up, and they're running 24 hours a day," smiles Weisman. He, meanwhile, would go on to found the tabletop-game company Wizkids, followed by the alternative reality game (ARG) firm 42 Entertainment, which created the 'I Love Bees' ARG used to promote Halo 2.

In 2011, he co-founded the game developer Harebrained Schemes, which went on to release games like Shadowrun Returns (2013) and BattleTech (2018), and has also worked with Disney on bringing interactivity into their resorts and cruise ships. Most recently, Weisman has been working on a program called Adventure Forge, which lets users design video games without the need for coding skills.

"My whole career has always been about the same three-legged table," says Weisman. It's storytelling, it's socialisation and its mechanics, and the mechanics are just in service of the other two. Whether it's building theme parks, or location-based entertainment centres, or video games, or tabletop games, or ARGs, or whatever it is, it's all about those same three table legs. And I always say that the learnings we got on the social dynamics side, on the social engineering, of the BattleTech Centers and Virtual World centres was infinitely more valuable and interesting than the electrical or software engineering."