Given the worldwide release of the Live A Live remake in July 2022, we thought it worth looking back at the creation of the original Super Famicom title, released in September 1994. If you've not had the pleasure of playing either the original or remake, our sister site Nintendo Life reviewed the Switch version of Live A Live and it scored it 8/10, giving it much praise.

Released roughly eight years after the original Dragon Quest on Famicom (1986), seven years after the original Final Fantasy (1987), and roughly five months after Final Fantasy VI (April 1994), Live A Live entered a world where many JRPG tropes were already entrenched. It would go against the zeitgeist, however, to forge something new and experimental, which even today feels original. It's interesting to consider that eight years after the template set by Dragon Quest, Live A Live was doing its own thing, and yet 36 years after Dragon Quest, while other JRPGs still slavishly adhere to some of its antiquated ideas, Live A Live's inventive little ensemble of stories continues to stand out.

Which is not to say that every post-Dragon Quest JPRG is derivative. Several tried to evolve the genre and, as we'll show, Live A Live itself influenced what came after, including Chrono Trigger and Parasite Eve. As astutely pointed out by Alana Hagues in her Nintendo Life review:

Early on in Square-Enix's remake it's plain to see the influences the game had on Chrono Trigger. From spanning multiple timelines to the inventive area of effect skills, and right down to the simple, sometimes deep story, director Takashi Tokita clearly used 1994's Live A Live as a springboard for his eventual masterpiece. But Live A Live deserves its own time in the spotlight, and after never officially being localised for the West, now this 28-year-old JRPG is finally getting the chance.

Live A Live was created by Takashi Tokita, whose portfolio is extensive and impressive. Some curated highlights include:

- Aliens: Alien 2 (MSX, 1987) - Graphics

- Rad Racer (NES, 1987) - Graphics

- Final Fantasy (NES, 1987) - Graphics

- Hanjuku Hero (FC, 1988) - Graphics

- Square's Tom Sawyer (FC, 1989) - Graphics

- Final Fantasy Legend (GB, 1989) - Graphics, Character Design

- Final Fantasy III (FC, 1990) - Sound Effects

- Final Fantasy IV (SNES, 1991) - Lead Game Designer

- Hanjuku Hero: ASH! (SFC, 1992) - Director

- Live A Live (SFC, 1994) - Director, Writer, Event Designer

- Chrono Trigger (SNES, 1995) - Director

- Final Fantasy VII (PS1, 1997) - Event Planner

- Parasite Eve (PS1, 1998) - Director, Scenario Writer

- Chocobo Racing (PS1, 1999) - Director

- The Bouncer (PS2, 2000) - Director, Dramatisation

- Nanashi no Game (NDS, 2008) - Producer

Tokita's major claims to fame outside of Japan are of course Final Fantasy IV, Chrono Trigger, and Parasite Eve; three highly acclaimed JRPGs which, each in their own way, broke new ground upon release, and are still loved by Western audiences. Over the years he has been interviewed many times, but almost always with an exclusive focus on these popular titles. It was only in Volume 3 of The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, during a four-hour interview, that he was able to go in-depth on his lesser-discussed creations. It resulted in over 11,000 words, of which we present some highlights here.

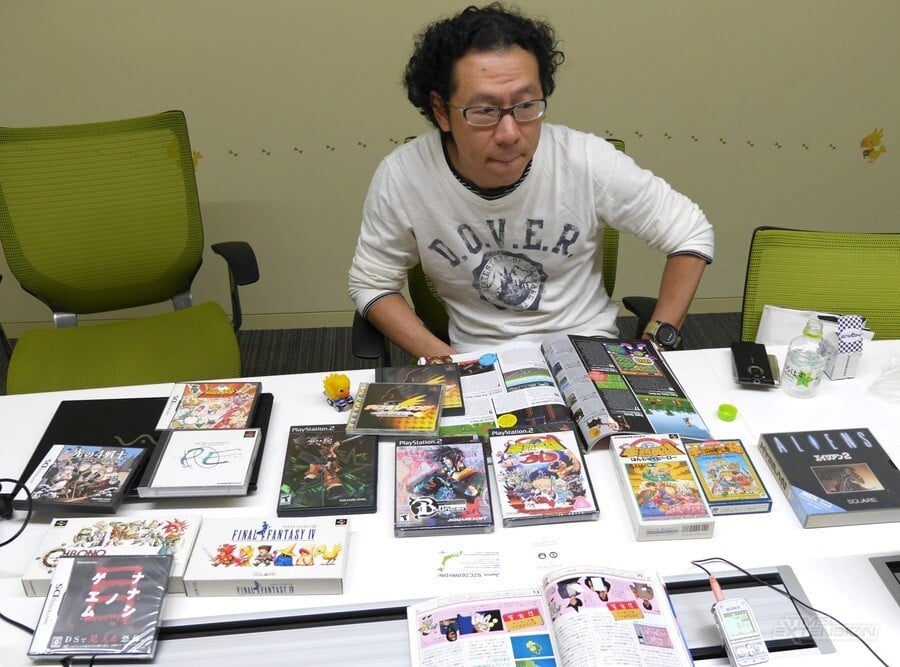

"I don't know that I've ever had a chance to go through my entire career like this! I never actually intended to make a career out of games - it was originally just a part-time job," laughs Tokita, looking over all his games spread across the table. "At the time I was into anime and manga, and discovered voice acting. So I started performing in hopes of becoming a voice actor. I was a trainee in a theatre group in high school; after I graduated I moved to Tokyo in hopes of getting solo work. It was when I was looking for a part-time job to support myself that I found a company that was recruiting videogame designers. I had wanted to do something creative for my part-time job, and I really enjoyed drawing, so I thought making games would be interesting, and went in for an interview."

Of all the interviewees in The Untold History books, Tokita was one of the coolest and most fun to chat with, having a sharp recollection of events and a genuine passion for games creation. He's also not afraid to lampoon his own creations or speak candidly. Tokita went on to describe his first job creating graphics for various computer games at ZAP Corporation, which we previously showcased twice when quoting Manabu Yamana. Tokita and Yamana worked alongside each other at ZAP and, after they both left, the two men would go on to helm rival series Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest respectively.

Tokita worked at ZAP for two years, but the workload was gruelling, and he felt his creativity being stifled. "Around that time I saw a commercial for Square's King's Knight for the Famicom," explains Tokita, describing his leaving. "I was really impressed with its graphics so decided to take an interview with Square. I had two years of experience at that point, so I was pretty confident. One of the programmers I worked with at ZAP was Manabu Yamana. Kan Naito was also a programmer there. It's quite a funny coincidence that just as I was leaving to join Square, they were both joining a company called Chunsoft, to make Dragon Quest on Famicom for Enix."

Tokita joined Square during its ascendance into what was the company's first golden age, moving beyond poorly selling computer games and focusing instead on major role-playing hits for consoles. During this time he worked alongside all the greats, including Hironobu Sakaguchi, Nobuo Uematsu, Nasir Gebelli, and Hiromichi Tanaka.

"Actually, my very first Square game was this here, Aliens: Alien 2," says Tokita, picking up his personal copy from the table. "I joined Square and one of the reasons they decided to recruit me was because they wanted to develop this for the MSX, and I had experience doing graphics for MSX. At that time, the planner for the game was Hiromichi Tanaka, the designer on Final Fantasy II and III, and also producer for Secret of Mana and Final Fantasy XI. The music and sound effects were done internally by Nobuo Uematsu. We had a lot of freedom. I was only 20 years old, so that was quite exciting for me!"

Before we dive into Live A Live itself, it's worth noting the Hanjuku Hero series, since this was actually the start of Tokita's experimentation with JPRG concepts. A small collection of surreal and comedic RTS titles, featuring an anthropomorphic egg hero, none have officially left Japan. They rely heavily on silly humour and language puns, making localisation difficult (fan translations exist though). The later PS2 titles resemble Sega's Dragon Force.

"The impetus for the Hanjuku Hero series was that RPGs like Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy were becoming big hits," begins Tokita, "so we thought it might be interesting to see if strategy / tactics games could become the next breakout genre. We played a lot of Western computer games. One was The Ancient Art of War, which had incredible real-time graphics, and that was a major inspiration for us." Keep in mind Tokita's explanation, since although Live A Live has a turn-based battle system, it's more focused on tactics and strategy than the preceding Final Fantasy IV which Tokita developed.

When we finally get around to discussing Live A Live, we unashamedly describe it as a masterpiece. We had to know more about how and why it was made. "Thank you," says Tokita, impressed with how much a foreigner knew about a game which never (at the point the interview was conducted) officially left Japan.

"We had just completed Final Fantasy IV, and RPGs had become a massively popular genre," he continues. "The other factor was the increase in memory size. We'd added in elements of various movie genres to Final Fantasy IV and V, particularly from sci-fi films and westerns, and I thought it might be interesting to isolate each of those genre elements and make a little story around them. Doing it in an omnibus format would be a way to really emphasise the strengths of each genre. We were developing Chrono Trigger more or less concurrently, so we were experimenting a lot with how to take advantage of additional memory, as well as how best to approach long-form storytelling. Another major inspiration was shattering the story-map-battle structure of RPGs. We wanted to have each chapter break that structure in different ways."

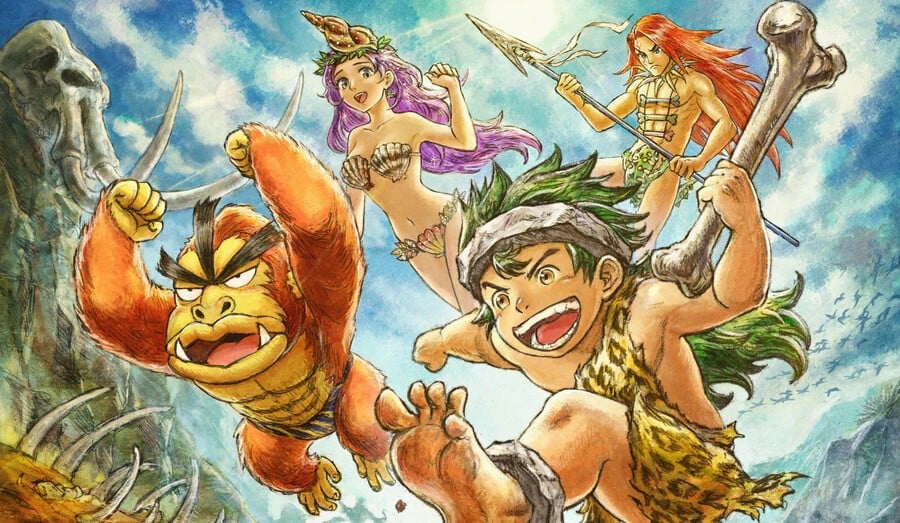

The biggest change up for Live A Live is, of course, how the story comprises a series of distinct chapters, almost like an anthology of mini-stories, each based on a time period. As Tokita points out, each of them breaks the traditional structure of JRPGs. From the prehistoric period to the wild west, to the present day, far future, and so on. Each chapter has its own hero, self-contained story, unique gameplay mechanics, and famous manga artist handling graphic design. Any of the starting seven chapters can be accessed freely, with only the final eighth to be unlocked. In a way, those opening seven are almost like seven distinct games, with just the strategic grid battle system tying them together.

Given how the selectable chapters went against the linear style of Final Fantasy, we ask if there was any resistance from management? "Not really, no," says Tokita, admitting that it wasn't exactly a new idea. "The company had already made Romancing SaGa games with the 'free scenario' system, in which you choose a character and begin the game from his or her section of the world." In fairness, other games had also tried distinct character-based chapters, including Dragon Quest IV and Phantasy Star III, but Live A Live took the idea to a whole new level.

"One thing management did push back on was our original plan not to display the hit points of characters in battle," Tokita adds. "The idea was that characters would fall to their knees or look weakened to reveal the extent of their damage; we thought that would be more exciting than showing damage in terms of numbers. But management said no to that. I had the same idea for Hanjuku Hero - while games may need to use numbers internally, at the time I believed that games are more fun when the numbers don't appear on the screen. The idea is to keep the parameters hidden so they don't distract from the game's visuals, the way it's generally done in more action-focused games."

Given the involvement of a different manga artist for each chapter, and the unique voice of each self-contained story, we asked if Tokita was involved in writing all the scenarios. "Not all of them, no," he says. "The scenarios for Genshi (prehistoric) and Kinmirai (near future) were written by the battle director, Nobuyuki Inoue, although I did the event design for those." We also ask which is his favourite. "Each of them is in a different genre, so picking a favourite is difficult - it's like picking a favourite child!" he replies with a smile. "But the Far Future chapter, in which we challenged ourselves not to include any battles at all, may be the most dear to my heart. I think we managed to capture something like the Resident Evil-style real-time adventure games of today in an RPG framework with that one. On the Far Future chapter, we made the storyline the main focus."

Keen-eyed players who enjoy this chapter may also notice several film references too. James Cameron's Alien being the most obvious. "Yes, Alien," agrees Tokita, adding, "As well as 2001: A Space Odyssey. The common element of those two films is the fear that comes from being isolated on a spaceship. Between the very limited number of people you can relate to, and the themes of survival, it's a situation that's very rich in drama."

We next bring up the Masaru chapter, pausing for effect and grinning. Tokita grins back, seemingly knowing where this is heading. We utter two words: Street Fighter? "Yes!" replies Tokita, laughing hard and tapping the table. The beautiful homage that is Masaru's chapter, and its inspiration, is inescapable, and he describes its creation excitedly. "The concept for that chapter was that we focus solely on battles. And getting Street Fighter II composer Yoko Shimomura to do the music for it only made it feel all the more like Street Fighter! <laughs> And the idea of defeating characters and then gaining their abilities, in order to defeat other characters, was very much like Mega Man, so you could say that was an inspiration as well."

It seems apparent that Tokita (if not Square itself) was a fan of Capcom's games. "You could say that," he admits. "In those days, Capcom was the king of action games. Do you know the World War II arcade shooting game, 1942? And Commando? I liked those. When I was at ZAP, I worked on the computer ports, so I was playing a lot of Capcom games back then."

At the mention of composer Yoko Shimomura, we also broached the subject of graphics, and how there were a lot of famous artists involved with the project. "We made the characters quite large for the era," adds Tokita, reflecting on how those graphics might be perceived today. "Personally, I'm quite a fan of it myself. Now that 3D graphics have evolved to a point where you can create film-like visuals, in a way, it's pixel art that feels more distinctly game-like. I wonder if younger users might find it especially interesting?"

What about cut chapters? Did anything have to be removed due to budget or time constraints? Secret of Mana infamously "nuked" about 40% of its text, according to Ted Woolsey, due to lack of ROM space. How complete was Live A Live? "Hmmm..." pauses Tokita, going over the chronology of development. "I believe we had planned to do those eight chapters from the beginning."

Given its originality, notable music, large visuals, inventive battle system, high production values, larger memory size, and renowned all-star development team, was there ever any talk of it being localised into English at the time of release? Surely Live A Live must have been a best-seller in Japan? "At the time the Japanese release wasn't very..." says Tokita, pausing to find the right words. "Well, I think it sold about 270,000 copies. I think that would be considered a hit nowadays, but at the time they were comparing it to Final Fantasy, and deemed it a failure. Timing was a factor. I think it would have sold better if we released it before Final Fantasy VI. If I recall correctly, the plan was to release it before Final Fantasy VI, but we had a delay, and the release order got reversed. After Live A Live was completed, I joined the Chrono Trigger team for the latter half of its development. I think Chrono Trigger took something like two and a half years? It started after Final Fantasy V and Hanjuku Hero on Super Famicom, but was released after Final Fantasy VI and Live A Live."

In the end, Final Fantasy VI hit Japan in April 1994, with Live A Live following in September, roughly five months after. Chrono Trigger launched about six months later in March 1995, making Live A Live the overlooked middle child. Despite its perceived failure in Japan, English-speaking fans clamoured for it, and in 2001 there was a fan-translation patch, with a second even better revamp released in 2008. We asked if Tokita was aware of these, showing him screenshots on our mobile phone.

"I have heard rumours about that," replies Tokita somewhat evasively, on first hearing the question. After looking at the screenshots, however, and seeing the unique fonts created for each chapter by the Aeon Genesis translation group, he responds more strongly, "Oh, this is incredible! I've never seen this before." A lot of discussion followed on the nature of fan translations, and the strong impression we got was that, while management didn't like the idea of players patching ROMs instead of buying product, the creators themselves were pleasantly surprised that Japan-exclusive titles were popular with foreigners.

While we've already mentioned how Live A Live helped influence Chrono Trigger, it also influenced the much later Parasite Eve, both in terms of synergising cross-publisher deals, and also structuring of the teams. Live A Live's publisher collaboration resulted in various famous artists doing character designs for each chapter, and Wikipedia has a good summary on this. Obviously, we asked the man himself about Square's partnerships.

"Game publishers and magazine publishers worked very closely together in those days," reveals Tokita. "For example, Live A Live was part of a collaboration with the publisher Shogakukan, who was launching a new game magazine at the same time. For Parasite Eve, it was published by Kadokawa Shoten, which was publishing a number of video game magazines in those days, due to the video game boom, and it may have been a part of a collaboration with them. Hironobu Sakaguchi suddenly brought in a copy and said, 'Let's make a game out of this book.' <laughs> He'd read the book on an aeroplane since he was going overseas a lot in those days."

As for managing the Parasite Eve teams, Tokita explains, "In Live A Live, breaking the game up the way we did caused the teams assigned to each chapter to get a little competitive with each other, and I think that ultimately resulted in a better game. There was a similar dynamic in Parasite Eve, where we broke the new staff into teams to work on different scenes of the game, inspiring a friendly rivalry that ultimately made for more interesting results."

This was right at the time when development teams were starting to balloon in size, and would be a precursor to the enormous team that helmed Final Fantasy VII. Tokita described how Square had gone from teams of just six people on a prominent MSX or Famicom title, to between 20 and 30 people during the Super Famicom era. Live A Live is sort of the midpoint with 47 staff credited and, when completed, staff moved over to Chrono Trigger, swelling it to 50 or 60 staff, finally topping out at just over 100 members.

Over the years Tokita has described Live A Live as his eldest child, because he was so involved in every aspect of its creation. Given this, it's a little melancholy that journalists focus so much on his Final Fantasy work. "Yes, but it's thanks to Final Fantasy that I was able to do all of this," replies Tokita, with reverence for the series that helped establish him. "I've worked on a lot of projects over the years; some big, some small, some successful, some not. I had a lot of those opportunities because of Final Fantasy. I was blessed to work on a series as big as Final Fantasy, but also to be able to make smaller games as well. I've been able to do this for over 35 years, and I'm very grateful for that."

Given that this interview with Tokita took place before the development of the Live A Live remake, several questions were actually on remaking the game. Did we perhaps plant the seed that led to the remake? It would be hubris to say yes, but we're not saying no either...

We leave you with Takashi Tokita's words on wanting to bring back Live A Live, thankful that he was able to do so:

I would love for people to be able to buy Live-A-Live again one day. I was hoping we could do something for the game's 20th anniversary [which would have been 2014], like a remake or something, but considering that we've never attempted anything like that before, I'm guessing we don't even have much of the game's source code anymore. But I think it would be fun to remake from scratch by just copying from the original. But this is a 20-year old game, and when you play it, it really shows. In this day and age the internet gives people access to everything, new and old, whether the original, physical version of it is still available or not. I would love to see old games like Live A Live or Chrono Trigger be remade. It's important to have systems that allow creators with more distinctive, less-mainstream visions to reach audiences who share their interests.

Fast-forward to the present day, and we're happy in the knowledge that Tokita's wish has been granted – in the case of Live A Live, at least.

Please note that some external links on this page are affiliate links, which means if you click them and make a purchase we may receive a small percentage of the sale. Please read our FTC Disclosure for more information.

Comments 2

Great article, which once again made me want to download the game. But I'm waiting for a discount.

On a side note, I welcome announcements of TE articles on the NL feed. I keep a list of websites I visit to a minimum, so I had to choose. And this way, amazing writing from TE does not get lost for me.

Great article. I don't know why, but I have a strange feeling we will get a HD-2D Chrono Trigger remake. It's time for a grand return of that game and it deserves much more than a cut and paste port.

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...