On Wednesday, 10th February 1988, Japanese police arrested nearly four hundred schoolchildren involved in a mass breakout of truancy in what a National Police Agency spokesperson later described as “a national disgrace”. The absenteeism was inspired by a video game, Dragon Quest III, a role-playing game released that day for Nintendo’s Famicom games console, and which sold a million copies. Its release proved so disruptive that the game’s publisher, Enix, promised the Japanese government that henceforth it would only release subsequent Dragon Quest games at the weekend or during national holidays so as not to goad students and office workers into calling in sick.

To date, the Dragon Quest series has sold more than 60 million copies around the world. Its closest competitor, Final Fantasy, which is published by the same company, boasts even greater success, with in excess of 100 million global sales. The Japanese RPG is not only a financial success; it is also one of Japan’s most enduring cultural exports. But in 1983, the role-playing game was almost unknown in the country, viewed as an American curio, with no relevance to the Japanese market. But Henk Rogers, a Dutchman who had arrived in the country by way of Hawaii a few years earlier, saw things differently.

Today, Henk Rogers is best known as the entrepreneur who convinced the Soviet Union to sell him the handheld rights to Tetris, the puzzle game devised by the Russian computer programmer Alexei Pajitnov. Rogers took a plane to Moscow, breaching the terms of his tourist visa, to meet with the officials from whom he sought permission to release a version of the game for Nintendo’s new handed, the Game Boy. That story was recently made into a film for Apple TV, in which the Welsh actor Taron Egerton plays the role of Rogers.

Tetris is not the only world-changing event Rogers helped to facilitate in video games. While a student at the University of Hawaii in the late 1970s, he and a group of like-minded friends fell in love with Dungeons & Dragons, the board-less board game in which players assume the role of a fantasy character and tour a fictional world, battling monsters and befriending strangers. "We had our own rules in Hawaii," Rogers, who retains a youthful charm and full head of long, silver hair at 69 years old, told us. He had moved to the island from his native Holland in 1975 to study. "We played constantly, using photocopies of the three original Dungeons & Dragons books. There would be a game in the campus centre that almost never ended. People would drop in and out of the adventure around class. Some weekends we'd start playing on a Friday evening, and we wouldn’t stop till Monday morning. It was a huge part of my life."

While Rogers was a socially confident young man, he was also an academic misfit. "I knew I would never work a nine-to-five job," he says. "So I took any class that would secure me computer time. That was my passion." Rogers studied any module that interested him, from psychology to zoology. At the end of his fourth year he met with the college advisors who told him that he had an additional year of core requirements ahead of him if he wanted to graduate. "I declined their offer and left that day."

Rogers departed for Japan ("I chased a girl to Tokyo") where his father worked in the gem business. Unable to speak, read or write Japanese, he joined the family company and worked for room and board. "There was a gap left from Dungeons & Dragons," he says. "I later found out there was a handful of people playing the game in Japan, but there was no community and certainly no cultural familiarity with the language of 'rolling a character'."

After a couple of years working in the gemstone business in Kofu for no salary, Rogers decided he wanted to make a video game, despite having no experience in the emerging field. He surveyed the market and, to his astonishment, realised there were no computer RPGs for sale in Japan at that time. "It was immediately obvious to me that the core difference between the two markets was that there were no computer role-playing games in Japan. The US had Ultima and Wizardry. But there were no such adventures in Japan. I thought: I could do that."

Rogers approached a publisher near where he lived in Kofu and sold them on the idea of building an RPG. "They promised to give me the hardware and I would pay them back through royalties," he recalls. Rogers bought an NEC-8801, which he considered the best and most powerful system on the market at the time, and began work on his game.

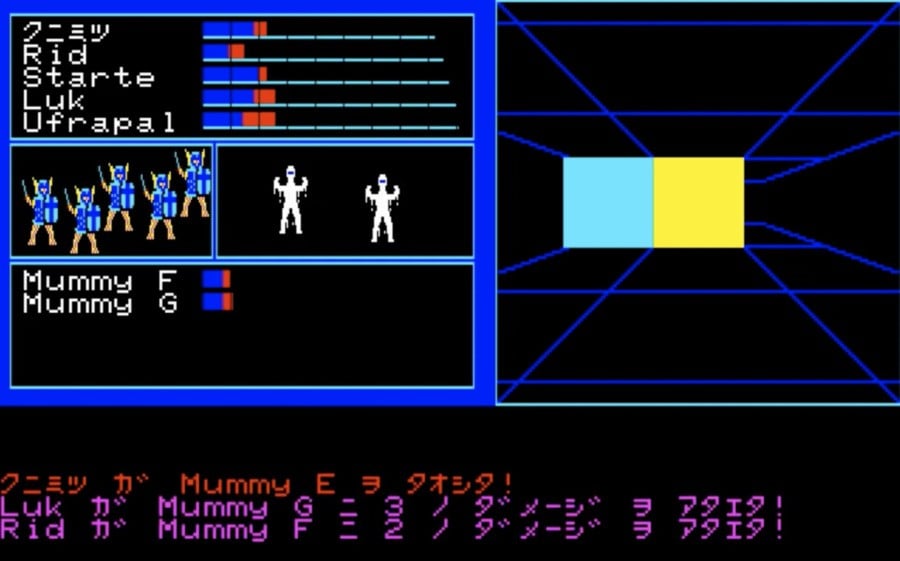

"My only experience writing code was some college assignments," he says. "I had never built a product. I had no idea what I was getting into. But I did have a bold vision for the game: a full Dungeons & Dragons game featuring fighters, warriors, wizards, clerics. All of that stuff." With only 64k of memory available, Rogers was forced to confine his concept to technological constraints, reducing the number of character classes to just one ("Warrior: I figured the Japanese could identify with that," he says) and removing any inventory, so that any items, armour or weaponry could be seen on the character, rather than nested in some menu screen. "Everything was visible," says Rogers. "Except, of course, for the 'hider’s cloak'. That was my crowning achievement. If you defeated this one invisible enemy in battle, then you’d win his cloak. It cost me no memory at all to include that item."

I had never built a product. I had no idea what I was getting into. But I did have a bold vision for the game: a full Dungeons & Dragons game featuring fighters, warriors, wizards, clerics. All of that stuff

As work progressed, the president of the company with which Rogers had a handshake deal for a 50/50 split changed the terms, offering Rogers just ten percent of all royalties. Rogers told them the deal was off. The President of the company told him he would have to repay the cost of the computer with interest. When the bill arrived, Rogers was shocked at the amount: $10,000.

In February 1982, Rogers took the subway to Akihabara, Tokyo’s neon-lit electronics district, to seek investment from a friend who worked in the gem business in Bangkok. He needed funds to finish the game, market and sell it as a product, and to pay off his debt to the publisher with which he had cut ties. The pair met in an electronics store, and Rogers loaded the prototype onto one of the machines to show it off to his friend. Soon, a group of Japanese children had gathered around to see what was happening. The friend agreed to give Rogers $50,000 in exchange for half of the company for the capital. His new partner had little interest in becoming meaningfully involved, however. "He told me he would handle all the accounting for me, but he never showed up once," says Rogers. Three years following the game’s release, Rogers bought back his share of the company for $200,000.

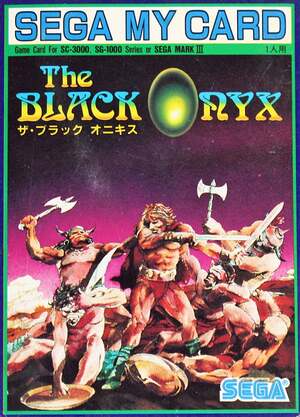

Rogers set himself a gruelling schedule. He wanted the game to be released before Christmas 1983, which gave him just nine months to construct the adventure from scratch. "I divided time into blocks," he explains. "I thought about how important each part of the game was and gave myself time accordingly. Then I’d work my ass off trying to get ahead. I would have an extra day or hour, and that would buy me the time to go back and fix earlier work that I wasn’t happy with." It was arduous work, but he had a workable plan and, by this point, a title for the game. Drawing on his family’s experience within the gem industry, he settled on: The Black Onyx.

They advised me to place a few advertisements in magazines and get my wife to answer the phone, rather than securing a publisher. The video game industry was so young at that time; nobody really knew what they were doing

Unable to read Japanese, Rogers was forced to rely on the girl he chased to Tokyo from Hawaii, who was now his wife. "She had no understanding of computers at all," he says. "It was the blind leading the blind. In the end, I had to work a great deal out for myself." As the game began to near completion, Rogers tasked his brother with testing. "I did a great deal of balancing," he says. "The best thing about that game is that I listened to those test players carefully and fixed every bug they found."

While his competence as a programmer and producer was evident, Rogers’ inexperience in business was revealed in a poor deal struck with Softbank, the largest software distributor in Japan at the time. "They advised me to place a few advertisements in magazines and get my wife to answer the phone, rather than securing a publisher. The video game industry was so young at that time; nobody really knew what they were doing." Softbank promised to buy 3,000 copies of the game but later reneged on the deal, buying just 600. This financial blow was compounded by Roger’s failure to create effective advertising.

He commissioned a friend back in Hawaii, Wes Adachi, one of the members of his former D&D group, to create a piece of artwork for the advertisement. "It was a drawing in the style of Frank Frazetta: a hero standing on a pile of monsters swinging a sword. The problem was that in Japan, nobody knew what the hell that meant. During the first month of the game’s release, we received just one phone call." Rogers hastily remade the advertisement, this time including screenshots. But again, the role-playing game proved alien to the Japanese audience. "The second month, we sold four copies," he says.

I sat down with each editor and asked them for their name. I typed this in and then asked them to choose the head that looked most like them... I taught them how to roll a D&D character. Then I left them to play

By January, the investment money was almost all gone. As a final attempt to drum up interest in the game, Rogers hired a translator and visited the offices of every computer magazine in Japan at the time. "I sat down with each editor and asked them for their name. I typed this in and then asked them to choose the head that looked most like them. In this way, I taught them how to roll a D&D character. Then I left them to play." The ploy worked. In April, every magazine carried an extensive review of The Black Onyx with pages of coverage explaining the arrival of this new genre. "It was unbelievable," says Rogers. That month the game sold 10,000 copies. It sold the same number in May, and again in June and so on. By the end of the year, The Black Onyx was the best-selling computer game for that year across Japan.

The young programmer made a string of savvy decisions. "All computer games at that time were sold for 6,800 yen," he explains. "I priced The Black Onyx at 7,800 yen and explained to retailers that, with 40 hours of gameplay, the game represented far better value for money than its rivals. More importantly, it also granted a bigger cut for the store." Rogers also packaged the game in a plastic case, which was more durable than the cardboard inserts used by other game publishers at the time. "It made the game appear more valuable," he says. "It was something people would keep out, on display; their friends would see the game and ask about it."

Rogers showed further marketing nous when he leaked news of a real-world prize for the first players to complete the game to the press. "The first one hundred people on every game platform would receive a real black onyx gem if they made it to the end of the game with a perfect karma score (achieved by not battling anyone weaker than your party). If they achieved this feat, they could send in the passphrase, 'Iggdrasil', and I sent them a gem along with a certificate proclaiming their success."

I picked the most complicated game possible, and I had no experience. But I slammed it. Programming is like that. Once it works, it’s so perfect it’s just sublime

The Black Onyx was such a success that Rogers immediately began work on a sequel. But by the time his team started on a third game, Japanese video game studios had begun to release their own take on the genre. Dragon Quest launched in 1986, and Final Fantasy followed the year after. "I was flattered on one hand," says Rogers. "But I also realised that I didn’t quite understand the Japanese aesthetic and way… These games were quite different to mine, and just struck a more effective cultural chord." He never completed work on Black Onyx III. Then, in 1988 Rogers, who had left programming to hunt for successful foreign games to bring to Japan, encountered a game called Tetris at a Las Vegas computer show. Rogers successfully licensed to Nintendo from the Soviet Union government. Tetris forever changed the course of his life.

Nevertheless, he looks back on those days with peculiar fondness. "It was the most ridiculous thing," he says. "I picked the most complicated game possible, and I had no experience. But I slammed it. Programming is like that. Once it works, it’s so perfect it’s just sublime." As for Dungeons & Dragons, Rogers still plays the game with his brothers from time to time. But no fantasy campaign can compete with his first quest for The Black Onyx. "If I think back on that journey, thirty years later, it’s like a ludicrous dream. It was the kind of project that’s so unlikely to work you’d only attempt when you’re young and brave and stupid."

(This is an updated and adapted version of a story first published by The Magazine in 2014, republished under license from Simon Parkin.)

Simon Parkin is an award-winning writer and journalist and a regular contributor to The New Yorker, The Guardian and many others. His latest book, The Island of Extraordinary Captives, was named as one of the New Yorker's Best Books of 2022 and won the 2023 Wingate Prize.