When does a game actually become real? Virtual Reality might be now all about headsets and controllers, but it still seems heavy on the "virtual" and short on, well, “reality”. Experiments in ARG, employing transmedia storytelling techniques, have been few and far between, with varying degrees of success. But, in the '90s, it seemed several developers were experimenting beyond the tried and true combination of “controllers and monitor”.

I’ve never been very interested in games, but I’m fascinated by a story that breaches the boundaries of the medium upon which said story is written and communicated

Director Maurizio Nichetti was one of the first to think about deepening the narrative of his 1993 movie Stefano Quante Storie with an interactive CD-ROM. He recalls that, while unfamiliar with games, he thought of the movie like a 'choose-your-own-adventure' book. In the CD-ROM, the player could see how each choice made by the character would alter the story in some way. The CD-ROM was co-written by Ottavio di Chio, also the main writer 1999's groundbreaking cross-media video game, The Iron Mask.

"I’ve never been very interested in games, but I’m fascinated by a story that breaches the boundaries of the medium upon which said story is written and communicated," says di Chio. He also recalls it’s been years since someone asked him about The Iron Mask. After the interactive CD-ROM, the writer began toying with the idea of combining real life and the virtual world. Di Chio mentioned the idea to Guido Bovolenta, CEO of Medialab, a small multimedia company. Scrapping the idea of using 3D graphics, they settled on a 2D point-and-click adventure. "With the game market already extremely competitive, we did not have the budget to develop a AAA game," recalls Bovolenta.

While being inspired by Broken Sword, di Chio recalls wanting something more. "I couldn’t help but feel there was something missing. I wasn’t fond of the idea of interacting in a strictly passive manner; I felt there was more we could offer the player than just staring at the screen." Thus, the idea was to bring teenagers a narrative experience that would make them feel like playing a game in real life. "The spark." continues Bovolenta, "came from watching David Fincher’s The Game, seeing Micheal Douglas going through all sorts of ordeals and surprises; we wanted the same kind of experience for the player."

As for inspiration from games, well, I did try to make the character design like The Secret of Monkey Island… not sure I succeeded, though!

With the Medialab team handling programming, Bovolenta and di Chio decided to also recruit several artists. Art director Mauro Perini handled character animation. He had graduated only three years prior and had barely played a game before. "I had also never owned a console, and it was my first time working on digital graphics. I basically did little else than work all day since I was new in the city, but the atmosphere was pleasant, and everyone did their best to make me feel at home," says Perini.

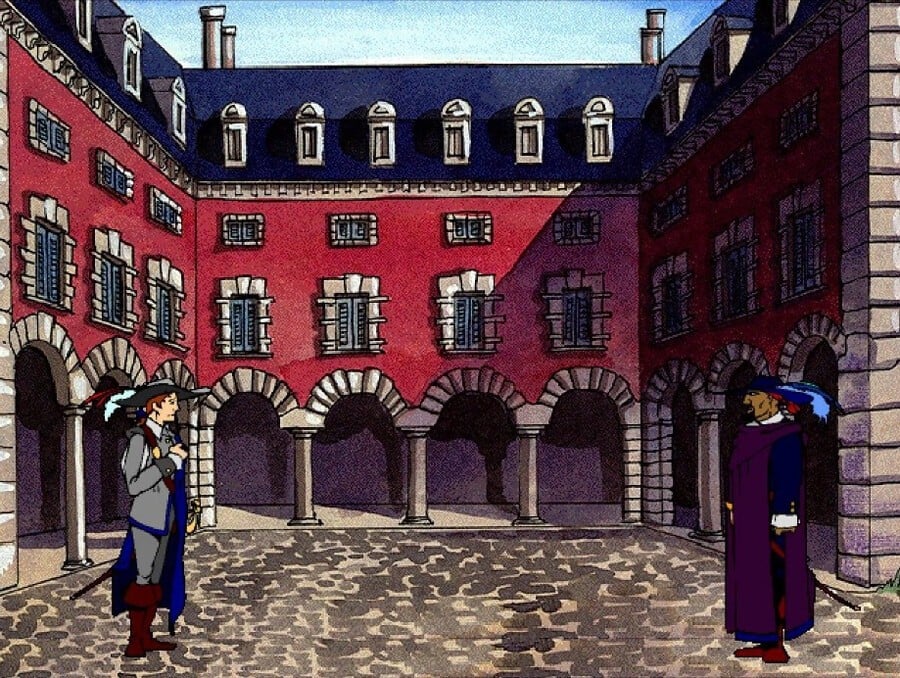

Perini mixed traditional drawing techniques with digital composition. "After scanning all my drawings, I coloured and animated them using Free Hand, which I learned how to use from scratch. I would animate and colour in each character, along with making the transitions between each scene. As for inspiration from games, well, I did try to make the character design like The Secret of Monkey Island… not sure I succeeded, though!"

Maurizio Galia, who designed the backgrounds, is, instead, a traditional visual artist that di Chio met in the Turin art scene. He recalls that "work started in spring of 1997; I remember falling in love immediately with the idea of drawing real places in Paris." Galia naturally drew inspiration from real life but also from art nouveau, and Venetian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi, for some of the in-game prison scenes.

The original idea was to shoot a live program, featuring actors playing different characters from the game. But that was quickly deemed too expensive and difficult to do

The story in The Iron Mask sees young pickpocketer Efrem, just out of prison, being hunted down by gangsters for unknown reasons. Apparently, the young man knows more than he seems to remember: while in prison, he has seen the face of 'The Iron Mask'. Indeed, the story recounted by Alexandre Dumas is repeating itself three hundred years later. Efrem needs to solve the mystery and escape the clutches of the 'evil satanic DJ' Madaski.

His first task? Actually getting out of prison. Using his release order, he’ll have to call up a phone number and get the code to open the door. This is the first bit of real-life interactivity: the player is supposed to find an actual telephone number in the game box to call. It was the first of a series of marketing ideas that di Chio and Bovolenta had conjured up.

First, they went to Mediaset, Silvio Berlusconi’s television network. "The original idea," recalls di Chio, "was to shoot a live program, featuring actors playing different characters from the game. But that was quickly deemed too expensive and difficult to do." They get in touch with mobile networking company TIM, which agreed to support the players by sending clues via SMS. Di Chio also recruited Madaski, DJ and electronic artist (of Africa Unite), to be featured in the game. MTV Italy also got interested in the project, providing two of their DJs who would pop up in the game several times.

Madaski was quite excited about the project – the only thing was that, well, he could not die in the game. "The project also ended up involving my image as an artist. I always took great care of my looks: dreadlocks, fur (synthetic!), leather and boots. I definitely looked the part of an evil guy. But, really, I am not," recalls the musician.

In the end, it was decided to shoot a series of short (8 seconds) ads that would contain hints for the players. They would be broadcasted daily on MTV, at 7 PM, for a few months. Unfortunately, none of these ads seem to be – at the moment – available anywhere online. Along with TV, Medialab also worked with Radio Italia Network to broadcast short radio segments with several references to the story.

They also cast an actress that would play the role of Anne Marie in real life. At the start of the game, Efrem would receive a real helpline phone number, so the actress would answer calls in real time, going through a script with the players. Anne Marie also gave Efrem an e-mail address that could also be used to ask for clues and directions.

While di Chio was busy on the marketing, development was going pretty slowly, ending up taking a whole two years. Still, Medialab managed to successfully complete Iron Mask on a small budget that, in today’s money, would be around 200k Euros. Bovolenta recalls that they succeeded mainly through the EU MEDIA fund, which amounted to roughly half the budget. Still, maintaining real-life interactivity beyond a few months wasn’t going to be sustainable.

This – recalls di Chio – turned out to be a problem when Iron Mask hit the stores in September of 1999. "By the end of March, all the interactive services would be discontinued," recalls the writer. "Retailers argued that it took them at least two months to sell a new product, hence only three months left to actually complete the game with the online services active." But that wasn’t all.

The two years in development seem to have also taken their toll on the overall pacing, as the game features several long conversations, only to grind to a halt with a rushed ending that sets up a sequel in Prague that, naturally, never came to fruition. Di Chio explains that "the ending was written while we were developing the final scene, we ran over schedule and had to finish quickly, in order to ship it before the end of the year."

Bovolenta recalls that the game, as a hybrid of edutainment and adventure, did not seem to find a place on store shelves. While some newspapers did pick up on the potential of the idea, it was a short-lived interest. The Iron Mask sold around 5,000 copies; it is nowadays little more than a curiosity for collectors. Amazingly, the original box also included a medallion that the players could wear in order to recognize each other while walking around.

The coincidence that no one who worked on the game had previous experience in the gaming industry – or was a gamer to begin with – might be the key in explaining why The Iron Mask feels disconnected from the rest of the market. Playing it today is quite like opening a time capsule: old Nokia-like cellphones to receive messages on, appearances of DJs that were supposed to be familiar to teenagers at the time, and references to MTV as almost an "underground cult."

The Iron Mask failed to excite the public imagination and remains all but forgotten nowadays. The 'transmedia' experience was not repeated often in the following years, with Missing/In Memoriam (2002) being one of the few examples of an adventure that made use of specially made websites and e-mail. "If we had developed it even five years later, I think it would have been received quite differently," comments di Chio. "Everything in our life is transmedia now; there is definitely a lot more narrative than action involved," the writer concludes.

It is interesting to see how such a small forgotten adventure game managed to kickstart the career of an experienced artist like Mauro Perini. At Ubisoft, he has also worked on titles like Beyond Good & Evil, Splinter Cell and, of course, the Mario + Rabbids series, on which he has served as Art Director. When I ask Perini if we can, in a way, attribute the success of Mario + Rabbids to The Iron Mask, he smiles and says, "I think we can!"