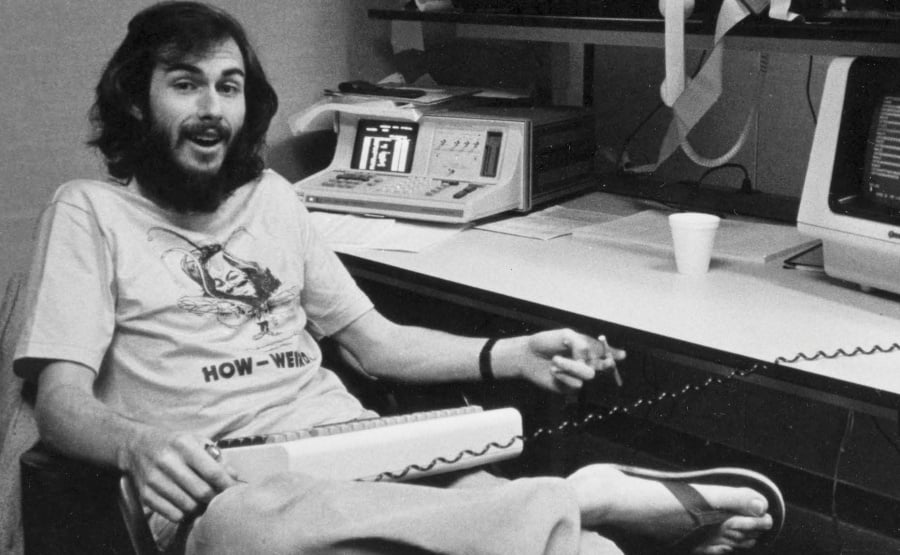

You may know Howard Scott Warshaw as “the man who created the worst game ever” or the man who was blamed for killing an entire industry. But for the last decade, he has also gone by another name: the Silicon Valley Therapist.

Back in 2008, Warshaw began training to become a psychotherapist after decades of working in both the tech and games industry. At the time he found himself at an impasse in his personal and professional life and needed a change. So, acting on the advice of a friend, he decided to re-enter education and plot a course to become a licensed psychotherapist. This may seem like a bit of an odd leap from his earlier work at companies like Atari, but according to Warshaw, it's the culmination of a "long and roundabout journey" that factors in a lot of his experience working in games. So, while talking to Warshaw for a recent article, we decided to ask him about this other side of his career too.

As Warshaw tells us, his interest in psychotherapy began all the way back in high school when he and his friend would constantly talk about their plans to create their own personality theory. Neither went on to pursue psychology, however, instead branching off into wildly different directions.

It was a productive, unhealthy, crazy, exciting, and super engaging environment that made some people wealthy and it made other people catatonics...

For Warshaw, that direction involved getting a job as a programmer at the popular video game company Atari in 1981. Atari, at the time, was one of the fastest-growing companies in Silicon Valley and was known as the creator of the Atari VCS home console as well as the successful arcade titles Pong, Breakout, Centipede, and Missile Command. Internally, the company possessed a very creative and progressive culture but often demanded a lot from those who worked there.

"It was a very unhealthy environment to be in and really engage in," says Warshaw. "Because it was the kind of environment that makes people give everything they have to this job, which means there’s nothing left over for the rest of your life. People who had other lives outside of Atari, those lives tended to starve, because all of their energy went into feeding Atari. And so, it was a productive, unhealthy, crazy, exciting, and super engaging environment that made some people wealthy and made other people catatonics who literally got carted off to institutions. There was a lot of pressure. It was a very high-pressure environment, and there were people who couldn’t take it, who just couldn’t deal with it, and literally lost their minds. I’d never seen that happen as frequently in any workplace than as I saw it at Atari firsthand."

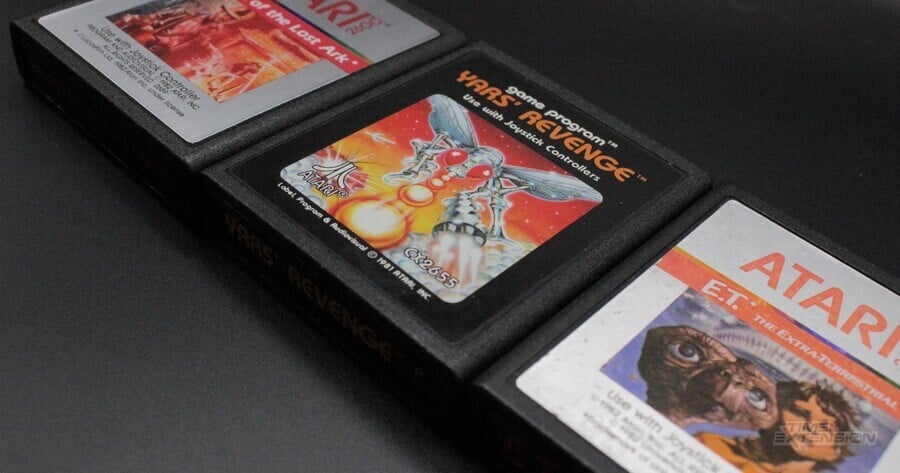

Warshaw worked at Atari for roughly three years and in that time released three games for the Atari VCS — Yars' Revenge, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. He eventually left the company in 1984, during the development of a fourth title named Saboteur (which was later released in 2004), and over the next few decades worked a number of engineering jobs while writing several books and producing a documentary on his time at Atari. Just as his 50th birthday was starting to approach, however, things started to fall apart and he felt the need to make a change.

He tells Time Extension, "Nothing was really working in my life, and I thought, ‘What do you want to do? What do you really want to do?’ I’d done many different careers, and the one I was in at that point wasn’t really sustaining me, and I needed to do something. Someone said, ‘What are you going to do? You need to do something.’ I said, ‘Oh well, I’ll go back and get a tech job.’ And they said, ‘Is that what you want to do?’ And I said, ‘Well, that’s what I need to do. My body is still addicted to food!"

Warshaw's friend put a hypothetical question to him: "If he could do absolutely anything, what would he do?" And the programmer immediately replied that he had always been interested in pursuing psychotherapy, before listing off a number of reasons why that would be a completely ridiculous or unpractical thing for him to do. The friend stuck at it though, and eventually convinced Warshaw to, at the very least, look into it.

"They talked me into wanting to research it a little and step by step everything then fell into place to move me into that thing," he tells us. "For a year and a half, I couldn’t find a tech job. I could not get a tech job. It just wasn’t happening. Then when I started to move in the direction of starting to become a therapist, I got a tech job that funded my education, and they laid me off just as I needed more time to start doing clinical work. It was like the perfect little boost along the way. And, as I got further into it, I realized more and more, that this is exactly what I wanted to do, really what I wanted to be, and interestingly, it was the first time I had been fully satisfied with the work I was doing since Atari."

What usually happens when an engineer goes to see a therapist is the engineer tries to spend several sessions and a lot of money explaining all the background that the therapist needs to get to understand the world that they’re in. With me, that’s two minutes.

Warshaw has been a psychotherapist for over a decade now, having opened his own private practice in Los Altos, California back in 2012. Speaking to Time Extension, he is adamant that his experience as a programmer has helped him in this new career path, arguing that it has let him overcome some of the prejudices that therapists and engineers have about one another to better treat his patients.

"Most therapists do not understand what it’s like to work at a high-tech, high-pressure, deadline-oriented position, and I do!" he tells us. "Very few people understand tight deadlines like I have had in my life, right? And a lot of engineers don’t understand that therapists can be pragmatic, practical, problem solvers, to address their issues directly. So, what usually happens when an engineer goes to see a therapist is the engineer tries to spend several sessions and a lot of money explaining all the background that the therapist needs to get to understand the world that they’re in. With me, that’s two minutes. They just tell me what it is they’re doing, where they’re working, what kind of programming they’re doing, and I get it."

Warshaw understands that some people may find his shift in career a little strange, but he's never felt that way about it personally. Instead, he simply jokes that he's always been a systems analyst, though now he's just decided to work on a more sophisticated piece of hardware: "the human brain".

You can read more about Warshaw's incredible career in games in his book Once Upon Atari: How I Made History By Killing An Industry or by reading our recent feature on his time at Atari.