In the 1995 cyberpunk movie Strange Days, the characters strap devices to their head that record their memories and physical sensations so they can be 're-lived', either by themselves or others. While the movie was ahead of its time in that regard (it is set at the turn of the millennium, and we still don't have that kind of funky technology), it made use of a media format which was, in '95, at least, expensive and highly desirable; in the movie, memories were recorded onto MiniDiscs.

You could argue that the film – which starred Ralph Fiennes, Angela Bassett and Juliette Lewis and was co-written by James Cameron, no less – was a poor advert for Sony's audio format. It flopped at the box office, and the device in question was hardly presented as a positive use of MiniDisc, but – in the mind of this author, at least – it did a lot to romanticise Sony's product. In the years before solid-state memory took over, the idea of carrying around data on tiny discs felt like the future – and for many people, it still does.

The MiniDisc Story

Sony announced the MiniDisc in September 1992. This was a time when the humble cassette (which, lest we forget, was never intended to be used to listen to music) was still the dominant force when it came to portable audio. CDs were popular at home, but portable CD players were still costly and bulky. The time seemed perfect for a new audio medium to arise, and who better to spearhead this revolution than the company which had created the portable audio industry overnight with the Walkman in 1979?

MiniDisc had a lot going for it. Not only were the discs small and portable, they could hold the same amount of audio as a compact disc – but with another key selling point. Blank discs enabled users to record their own albums, very much like the 'mix tapes' which were popular during the era of cassettes. Most MiniDisc players had the recording ability built-in, permitting users to record (usually in real-time) from their source using an optical connection and then manually add the track names afterwards. It was a laborious process – but one that, compared to other options at the time, felt like the future.

It's perhaps not a spoiler to point out at this juncture that MiniDisc was not the Walkman-level success its creator had hoped for; in 2010, Sony announced it had sold 200 million Walkman personal stereos. A year later, when it ceased production of MiniDisc, it confirmed only 22 million players had been sold.

"Looking back, it’s pretty clear that the MiniDisc didn’t take off in the West due to cost," says web designer and MiniDisc junkie Jake Smith. "The first MiniDisc portable player was $750 (that’s £590 in today’s money), putting it well out of reach for anyone but serious musos and gadget freaks. At its most attractive price point, it was still close to $250 – around £200 now. Pre-recorded MD albums didn’t help either, being priced around £16–20 back in the day, against the standard £12–14 price of a CD. At these price points, it wasn’t an attractive proposition when CDs were cheaper, and cassettes were in every car, room, dorm and could be copied over and shared. The experience of listening to and sharing music elbowed out the option of higher quality."

For Smith, MiniDisc's appeal was niche – but it's what led him to become a lifelong fan of the media. "I bought my first MiniDisc player, a Sony MZ-R30, brand new from Currys in late 1997. I had a full-time job as a 'multimedia designer' – my first web dev job – and had started downloading badly encoded low-bitrate MP3s of ska-punk bands, like Less Than Jake or college radio bands like Harvey Danger, via the internet. You couldn’t buy these types of albums in the UK without going to specialist importers, so being able to download a couple of tracks (at a speed of like 3Kb/s!) and record them to MD for the journey to work was geek heaven. Discovering music was so exciting back then. That introduced me to so many new bands and is responsible for my huge CD collection – more than anything else in my life."

While MiniDisc suited users like Smith, it found itself being ignored by many people in the West, despite a fairly aggressive advertising push by Sony. However, one region where MiniDisc fared better was in its homeland. "It has to be said the MD should be considered a success in Japan," says Smith. "CDs cost twice as much over there – being subject to a law that allowed owners of copyrighted material to set a minimum price for their new releases – so hiring a bunch CDs from a lending library for the cost of one new CD, then dubbing them all to MiniDisc, saw a great take up of the medium in Japan. So much so that Sony (and other MD hardware manufacturers) were taken to court by the Japanese record industry; the defendants heavily backed the rental outfits to support the continued sale of MiniDiscs."

Even so, Japan's love for the MiniDisc wasn't enough to keep it relevant, and the march of technology sadly spelt the end for the format. "By the time the price was coming down in the West at the end of the '90s, MP3 players were beginning their unstoppable march to popularity," laments Smith. Ironically, this was around the same time that Sony gave MiniDisc a shot in the arm via the 'NetMD' standard, which effectively turned units into MP3 players; discs were now capable of holding up to 32 times the number of tracks due to improved encoding. This made MiniDisc an attractive proposition well into the 2000s, but by the time the iPod showed up, the writing really was on the wall.

The State Of MiniDisc In 2023

Despite fading from memory for many people, there are those who continue to love the format. "Since the late '90s, I’ve never stopped using MiniDiscs," says Smith. "I might go on a bit of a hiatus every now and then, but they’ve always been a constant. A bit like the way a games console might get shelved for a couple of years, and then you get the urge to play something. I will admit, my collecting and use of them has increased in the last ten years."

The burning question, in this case, is why would you pick MiniDisc over a smartphone with Spotify installed – a match which gives you access to a broader selection of music than you'd ever reasonably need? Ironically, many people find that MiniDisc's limitations are what make the format so appealing in the modern era.

"I became aware of my own frustration in choosing music when doing nightly walks," continues Smith. "The walks took just short of an hour and were a perfect opportunity to listen to music without distraction. When choosing music on an iPod or a phone, some evenings, I was nearly 10 minutes into the walk before I could decide what I wanted to listen to. The paradox of choice! Less is more! With MiniDiscs, I’d reach into a box and grab two discs, and that was it. I was stuck with what I’d physically picked up. There were times the music didn’t match my mood, but it was tough shit – try the other disc! It had the effect of revisiting a lot of music I simply wouldn’t have put on and listened to if I was scrolling through an iPod or iPhone."

MiniDisc, with its cute and tactile discs, also speaks of a forgotten era where physical media was king. Those who grew up in the '80s will no doubt recall the buzz of exchanging mix tapes with friends at school and discovering new music in a way which is a little more intimate than today, where algorithms decide what track you should listen to next.

"Playing music through your laptop or streaming to a phone, the music doesn’t exist in a tangible form," says Smith. "The process of recording to MiniDisc, then entering track names by hand with the remote (before NetMD) was a commitment. You could even go the whole nine yards and design graphics and print sticky back paper and cut the labels out… I rarely do that now, preferring a Dymo LetraTag for labelling discs!"

And that's just the discs themselves – the MiniDisc players offer even more appeal. During its short time in production, MiniDisc was blessed with a wide range of playback-only units and player/recorders – some of which were portable, while others were Hi-Fi separates or built-into stereo systems (in-car MiniDisc players were also a thing at one point). Sony also licenced the technology, allowing companies like Kenwood, Sharp and Awia to produce their own players.

Even viewed through today's eyes, these compact devices are technological wonders. "The portable players are little marvels," says Smith. "Barely larger than two discs stacked, the spring of the lid and the tactile buttons are fascinating. How have they crammed so much cool shit into such a small enclosure? Much like Nintendo, Sony knew how to shift units in Japan, and there are so many hardware variations – with slight incremental improvements – between releases."

There are other reasons why people continue to treasure their beloved MiniDiscs. "Whilst I do have a Spotify account for the convenience, their compensation model to artists is infuriating, and the bit rate is fine for on-the-go headphones, but I’d prefer better," adds Smith. "I will try and buy lossless from Bandcamp when possible, and drop the songs to MD. There are also a lot of older CDs from the early '90s in my collection that I’m pretty sure won’t ever get a release on the streaming sites, and being able to have them to hand on physical media makes me happy. I have a Plex music server for my lossless ripped CD collection, but we’re back to the paradox of choice."

And perhaps most important (and amazing) of all is the fact that, despite being a technology that is now decades old, MiniDisc has the capability to outperform its modern-day rivals. "MiniDiscs sound great; the audio processing in the little units is excellent, and for me presents a big wide soundstage, with little to no signs of audio artefacts from the compression with the later ATRAC4 and Type-R equipped units," Smith says. "As mobile phones and Personal Media Players have become cheaper, the components within them have generally been sourced to be low cost. The last good iPod was the 5.5 with the Wolfson DAC chip; after that, the quality has measurably declined. Coupled with low Spotify bitrates, the sweet siren sound of the MiniDisc was too hard to ignore."

Getting Into The MiniDisc Game Today

If you're reading this feature and feeling the undeniable pull of eBay, then perhaps you're wondering if Smith has any tips or advice relating to purchasing a MiniDisc player in 2023. Guess what? He does. "If you’re buying your first unit, make sure it can record, or you’ll have nothing to listen to. Used portables with discs that can be re-recorded to are easy to find on eBay. Hi-fi separates are fairly easy to come by, as are the mini/micro/bookshelf stereos."

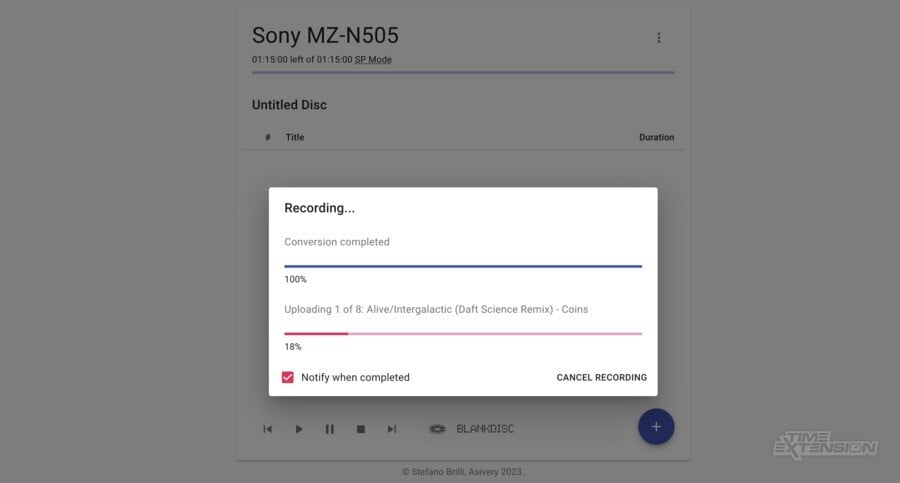

"To make your newfound hobby even more pleasant, make sure you go for a NetMD-enabled recording unit, which will most likely be a portable. With one of these, you can hook it up to your computer with USB and drag and drop music into a browser and transfer the songs – titles and all – much quicker than recording via the optical input. It's now possible to do this via a web-based app, amazingly. The explosion of reverse engineering and deep diving from the MiniDisc community in the last five years has been amazing."

We live in a world where rechargeable batteries are the norm, but sadly, our tech usually comes with them built-in, so user servicing isn't always possible. This is yet another reason why MiniDisc is attractive; while many units had hard-to-source internal batteries, they were almost always replaceable – while other units use the humble AA battery for power. When buying a unit today, it pays to be mindful of these differences.

"A lot of the MD player units don’t use AAs as their main power source, opting for the slimmer 'gumstick' batteries," explains Smith. "You can buy 'new' ones of these on Aliexpress, but they don’t perform too well, in all honesty. However, some enterprising MD lovers in Hong Kong have been manufacturing LiPo batteries in a 3D-printed gumstick-sized shell, with a USB-C charging port. I picked up two, and they’re so useful to have on hand. Unfortunately, some of the more premium models from Sony have custom batteries and sourcing replacements can be difficult if not expensive."

Speaking of cost, the low volume of sales for pre-recorded MiniDisc albums back in the day has resulted in almost all of these – irrespective of quality – becoming collector's items. Even the most embarrassing of albums released during the '90s can now fetch two, three or even four times its original cost – if not more. "The price of pre-recorded albums and players in the earlier days meant that sales were weak, and the released MD albums are traded on forums, marketplaces and eBay," Smith comments. "In my honest opinion, a lot of the music released on MD was mainstream rubbish back in the day."

Amazingly, the small-scale rebirth of MiniDisc has even attracted the attention of indie artists and bands; musicians are using MiniDisc as a means of distributing their music to a receptive audience. "Riding the wave of the MD revival, you will find bands on Bandcamp releasing their latest albums on MiniDisc," explains Smith. "As far as I can tell, the bands are buying up sets of new-old-stock MDs and having a cover UV printed over the face of the plastic disc. It's really great to see, even if I can’t see them doing large numbers."

MiniDisc And PlayStation – A Family Affair?

Of course, it would be remiss of us to talk about MiniDisc in this amount of depth without acknowledging its connection to video games. When Sony released its PlayStation Portable handheld in 2004, it did so alongside a new disc media: Universal Media Disc, or UMD for short. While UMD wasn't recordable, its design was clearly an evolution from MiniDisc. The disc itself was encased in a protective caddy, and the PSP's pop-out disc tray operated in very much the same way as those seen on many MiniDisc players. Sony clearly took what it had learned from MiniDisc and applied it to its handheld console, save for one thing – it didn't include a protective sliding panel, so the disc itself was 'open to the elements' when not in use.

If you're still confused about why anyone would spend good money on old-school optical media in 2023, Smith has some parting words for you. "It depends on what you want out of a music player. Do you want the ease of using a more modern solution like a Fiio PMP or the recent Sony Walkmans that use SD cards and play FLAC/ALAC etc., or do you want to spend a bit of time curating a physical library of music you love? If you fancy the latter, and enjoy putting in a bit of effort, I think you’ll be rewarded for your patience and perseverance."

For Smith himself, his undying love for Sony's 'forgotten' format is driven by many factors. "There’s so much to love about the MiniDisc; there’s not one individual thing that kicks off my dopamine rush. The industrial design of the portable players, the tactile feel of the clunks, clicks and whirrs, I enjoy how the MiniDisc colours the music, and sets a big soundstage, the clarity of separation. The online community that is making these little machines more usable and useful than they ever were during their heyday. Importantly, the act of putting music on. And like any collector, I like the fact that once I’ve used my latest player for a couple of months, I can hop online and start eyeing up a new unit that I haven’t owned before!"