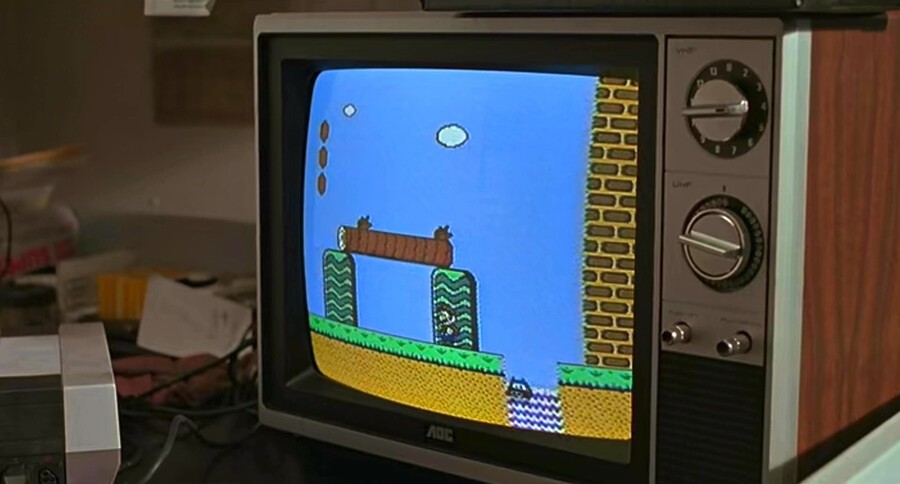

Nintendo may have struck gold with its recent efforts to crack Hollywood, but back in the late '80s, the notion of fusing the worlds of video games with movies was a totally alien one, as evidenced by notable box office bombs such as 1993's Super Mario Bros. and 1994's Double Dragon.

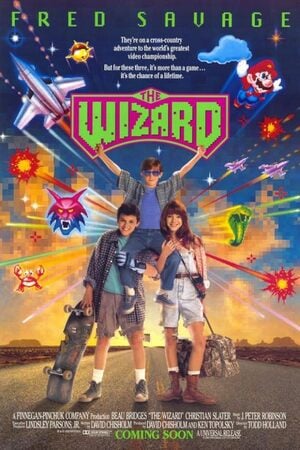

Before those came along, however, Nintendo tested the waters with a 1989 movie about video games called The Wizard. Penned by David Chisholm, directed by Todd Holland and bankrolled by Universal Pictures, the film was conceptualised by Universal's Tom Pollack as a video game version of Tommy, the 1975 "rock opera" movie based on The Who album of the same name. Pollack pitched the idea to Nintendo of America's marketing department, and the gaming giant was on board.

Rather than focus on a particular franchise, it was a traditional coming-of-age road movie with a surprising amount of human strategy at its heart – and video games were the vehicle that drove the narrative forward, rather than the story's sole reason for existing.

Budgeted at $6 million, The Wizard generated $14.3 million at the box office, so it can hardly be considered an out-and-out bomb – yet the critical reaction at the time was nothing short of scathing. The late, great Roger Ebert labelled it "a cynical exploitation film with a lot of commercial plugs", adding that it was "insanely overwritten and ineptly filmed" before citing it as one of the worst movies of the year.

However, as is so often the case with these films, Ebert wasn't The Wizard's target audience, and it has since become a cult classic, not only for its inclusion of Nintendo's hottest NES games but for its heartfelt portrayal of a broken family trying its hardest to heal following a devastating tragedy.

The Wizard turns 35 this December, and to mark this momentous occasion, we've pulled together interviews with Todd Holland (director) and Luke Edwards (Jimmy). These discussions took place at various points over the last 20-odd years and have been edited to present the flowing narrative format you see here.

I'm also indebted to Anthony Maurizio, whose 2014 interview with Holland has been combined with my own discussion with the director from 2009, which formed the basis of a feature on the film which was published in Retro Gamer magazine. That interview has been reproduced here in its entirety for the first time.

The Key Players

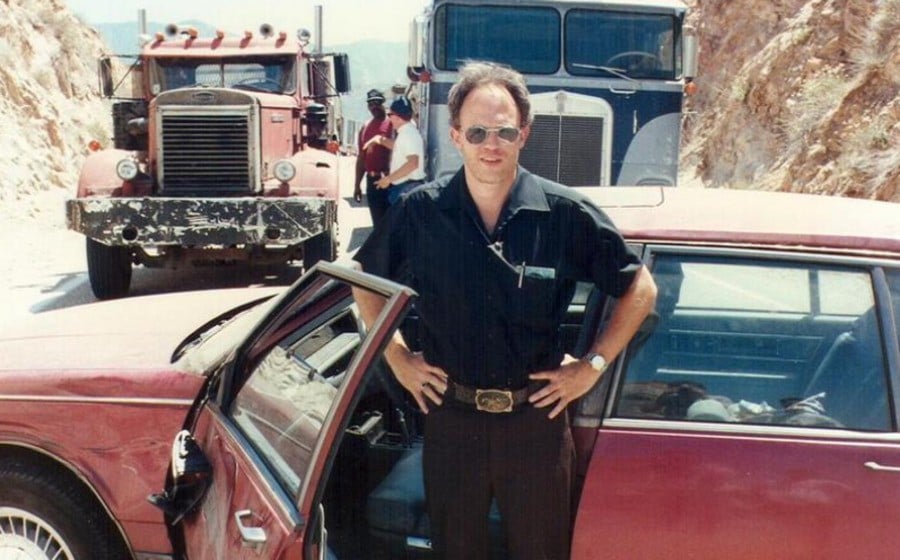

Todd Holland (Director)

An award-winning director, Holland directed over 50 episodes of The Larry Sanders Show and 26 episodes of Malcolm in the Middle (he won Emmy awards for both).

He has also directed episodes of 30 Rock, Steven Spielberg's Amazing Stories, Max Headroom, Twin Peaks, Grace & Frankie, My So-Called Life, Friends and Shameless.

In addition to The Wizard, his movies include 1989's Krippendorf's Tribe (starring Richard Dreyfuss), 2007's Firehouse Dog (starring Josh Hutcherson) and Monster High: The Movie (2022) and its 2023 sequel.

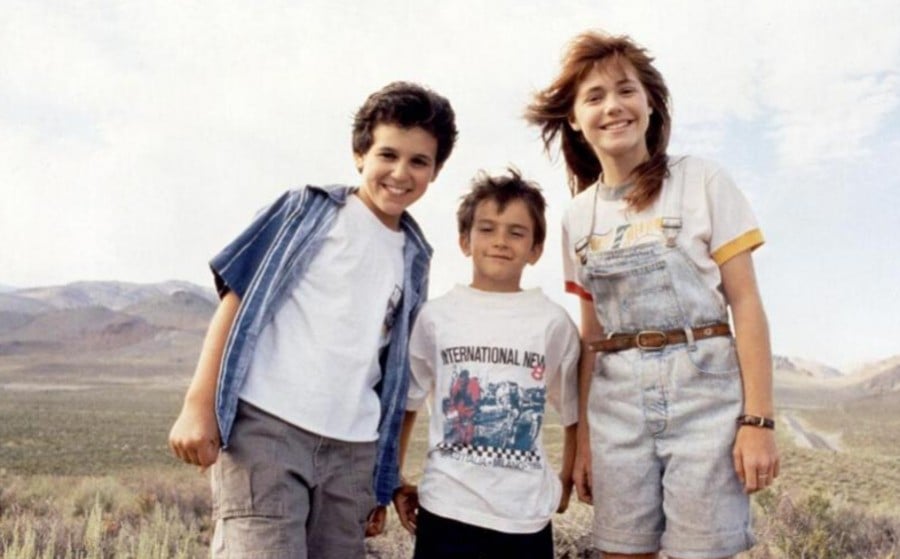

Fred Savage (Corey Woods)

One of the biggest child actors of the late '80s and early '90s, Savage is best known for playing Kevin Arnold in the American television series The Wonder Years, which ran between 1988 and 1993.

In addition to The Wizard, Savage has starred in movies such as The Princess Bride, Vice Versa and Austin Powers in Goldmember.

He has directed multiple TV shows in more recent times, such as Boy Meets World, Even Stevens, That's So Raven, It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Modern Family, 2 Broke Girls and the 2022 reboot of The Wonder Years.

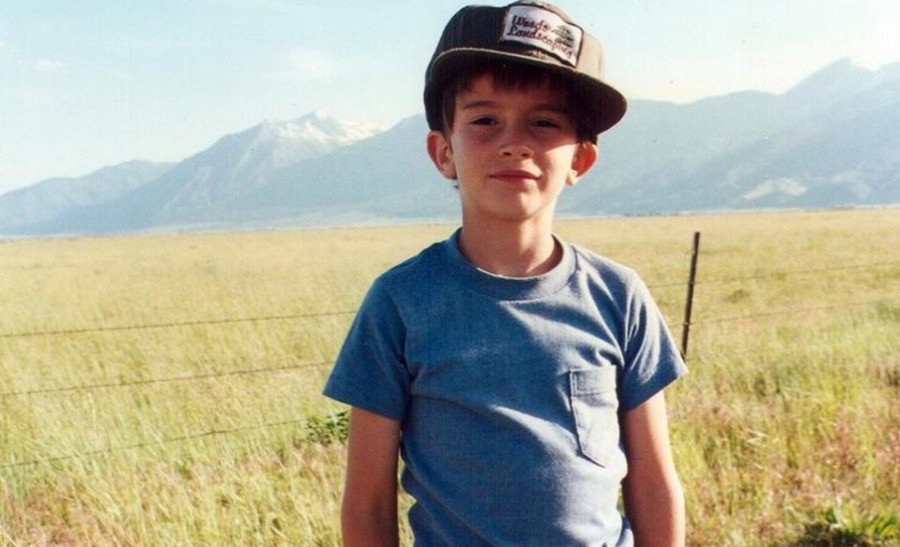

Luke Edwards (Jimmy Woods / The Wizard)

Edwards began his career as a child actor in ABC Afterschool Specials (1988) and 21 Jump Street (1989) before getting his big-screen break in The Wizard.

Since then, he has appeared in a wide range of TV and movie productions, including American Pie 2 (2001), Jeepers Creepers 2 (2003), True Detective (2015) and NCIS (2019).

Christian Slater (Nick Woods)

Slater's role in 1988 Heathers catapulted him into Hollywood's elite, landing him roles in films such as Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Interview with the Vampire, Broken Arrow, True Romance and many more.

He has also starred in notable TV shows, including the critically acclaimed Mr. Robot and Netflix's adaption of The Spiderwick Chronicles.

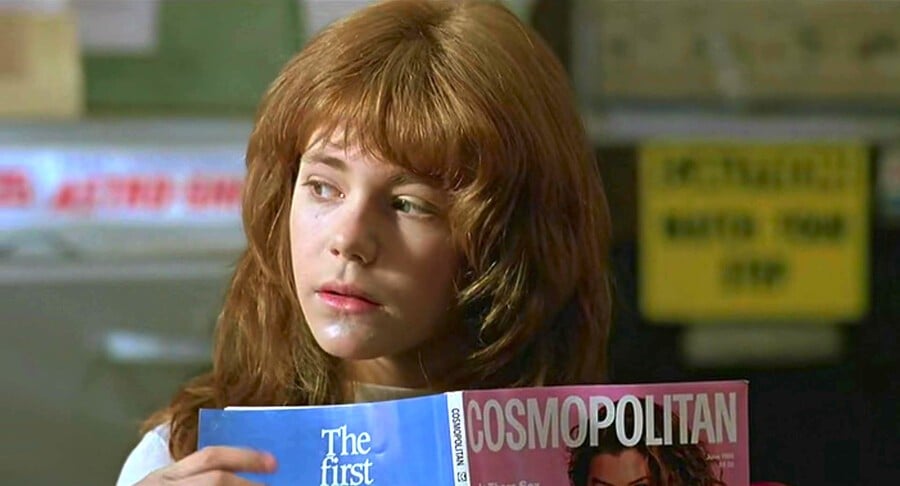

Jenny Lewis (Haley Brooks)

Lewis began her acting career in TV commercials before appearing in series such as The Golden Girls, Life With Lucy and Baby M.

In addition to appearing in The Wizard, she also starred in the movies Big Girls Don't Cry... They Get Even, Foxfire and Pleasantville.

Today, Lewis is more famous for having been the lead singer, rhythm guitarist, and keyboardist for the indie rock band Rilo Kiley. Rilo Kiley broke up in 2014.

Lewis has five solo albums to her name: Rabbit Fur Coat (2006), Acid Tongue (2008), The Voyager (2014), On the Line (2019), and Joy'All (2023).

Beau Bridges (Sam Woods)

Brother of Jeff Bridges and son of Lloyd Bridges, Lloyd Vernet "Beau" Bridges III is a three-time Emmy, two-time Golden Globe and one-time Grammy Award winner who has starred in numerous movies and TV shows during his long and distinguished career.

Will Seltzer (Putnam)

An actor with credits in movies such as Baby Blue Marine (1976), Citizen's Band (1977), More American Graffiti (1979) and Johnny Dangerously (1984), Seltzer's biggest claim to fame is arguably the fact that he was almost cast as Luke Skywalker in 1977's Star Wars; he was reportedly George Lucas's second choice for the role behind Mark Hamill.

Preparation And Casting

How did you become involved with the project?

Todd Holland: I had developed a few great feature projects at Universal – all of which died ignominious deaths. And I was frustrated and wanted to make a film so I read The Wizard on a Thursday, interviewed for the job on Friday, got the job and was prepping the film on Monday. We were shooting five weeks later – which is an incredibly short prep for any feature. The rush was all about Fred Savage’s TV schedule for The Wonder Years – he had just certain weeks off to shoot the film, and we had to start on time.

To be honest, Universal didn't want me to direct it. They wanted a TV movie director — a "tradesman" to come in and get the job done. But I'd grown up loving kid adventure movies — and all the "fancier" movies I'd developed at Universal had fallen apart one by one. I wanted to direct a feature badly. The president of Universal Pictures literally sat me in his office and told me all the reasons why he didn't want me to direct it. But I loved the adventure of the story; I loved the "kids against the world" element. To be honest, I did not play video games at the time. And I actually sold that as my strongest suit for the job — the movie needed to make video games interesting to everyone, not just preach to the converted. And I think that's why it worked.

Luke Edwards: The Wizard was one of my very first jobs. I did some commercials and a few very small TV roles, including playing a very young Johnny Depp in 21 Jump Street. Then, I got quite a big break when I was cast as a young Steven Stayner for the mini-series I Know My First Name Is Steven. That got great recognition, and it was actually a very well-made piece of work, especially for a TV mini-series. To this day, I still get recognized for that role, which is surprising as it was so long ago and I was so young. I think it affected people deeply.

Did you have much in the way of preparation work before the cameras started rolling?

Todd Holland: As I mentioned, the only actor attached was Fred [Savage]. So, I hired casting director Mali Finn (later to become famous for casting all of The Matrix films, Titanic, and dozens of brilliant movies), and she and I cast the film. We found Luke fairly early. I met with Beau [Bridges] and convinced him – and then once I had Beau, I was able to convince Christian [Slater], who had just made a splash in Heathers, because he was interested in working with Beau, having done a film with Beau’s brother, Jeff Bridges.

Fred Savage was something of a hot property when the film was produced. What was it like working with him?

Todd Holland: Fred was really amazing. Everywhere we went while shooting, everyone recognized him. It was a big deal. I mean, people lined the streets in Reno as we drove in, shooting the scene where they’re in the back of the truck — and girls are screaming Fred’s name and hooting and waving. And Fred was 12 years old (he turned 13 while we were shooting) and I was always stunned at the grace with which he handled all that attention. He was always such a nice, polite kid. But then, his family was solid and strong and very involved.

Luke Edwards: I must admit that at that time, I was completely oblivious to Fred's success and fame, which was probably for the best. I've always been the type of person who doesn't necessarily pay a lot of attention to who is doing really well in the industry. I have my own favourite shows and interests, so if he were, for instance, voicing one of the roles on The Simpsons, I would've known exactly who he was and been very impressed — starstruck, even. As it turned out, I didn't watch The Wonder Years at eight years old — I think I was primarily concerned with my G.I.Joes!

What about Christian Slater? He was about to become a massive star – what was he like to work with?

Todd Holland: Christian was terrific. And very, very much 19 years old. He liked to have fun in his time off and slept so late every morning that he had to be shaken awake by a Production Assistant (who had to be given a key to his hotel room) every morning because no clock radio could wake him. But he was hard-working and a real team player. Just a good guy. He and Beau really were great together.

Luke Edwards: Again, I was pretty oblivious to who anyone really was. Christian and Beau were both so nice to me and my mom, I really only knew them as friends. You have to remember also that I didn't have a ton of material with both of them. Most of my time on set was spent with Fred and Jenny, so I got to know them well.

A side note: one of my favourite movies right after that job was Heathers, which I was probably too young to be watching, but Christian was so good in that movie, and for me, that's the character and performance that I'll always remember him for. So I guess I was introduced to actors on the job and then, after, began to appreciate their body of work.

Will Seltzer was fantastic as Putnam – a cold, calculating villain with a dash of comedy. Do you have any specific Putnam stories or memories?

Todd Holland: I love that you pointed Will out specifically. Will was a friend from my acting class, and when we had trouble finding a great comic villain, I suggested that Will audition. He was great and won the role, but I don't know if that would happen today. He had almost no resume at the time, and today, even small movies cast "up" every role. It was a simpler age in 1989, when a boy could say "shit" in a family film, when you could show real "Coke" cans without asking permission or paying anyone for the right, and when the best actor could still win the role – even if they were nobody.

Beau Bridges puts in a fantastic performance in this movie, especially in the final tear-jerking scene. What was it like working with him?

Todd Holland: Beau is the consummate pro. He was the movie star in our cast – and really raised the bar for everyone to work hard, play, enjoy and get the job done. Beau always understood how much I wanted the film to work on an emotional level – I mean, there were a lot of complex emotional layers suggested in the script – but the trick was to make it all real and keep it at the right level for a family film about video games. No one was smarter than Beau about finding that level.

Jenny Lewis, who played the key role of Haley, would later find fame in the world of music. Is it true you had to fight with the studio to cast her?

Todd Holland: The biggest fight with Universal casting was over the role of Haley. Universal had a young girl, a Texas beauty-queen type that they really wanted. She really was not up to the role acting-wise at the time. And I had a fantastic young actress (whose name I can not recall) that Universal felt wasn’t cute enough. And so we were at an impasse – it was a real fight. And out of the blue Mali Finn found this young girl named Jenny Lewis – a miracle – beautiful and talented – and we were golden.

Jenny was terrific, such a gifted actress and such a great kid. I had a really good time working with Jenny and Fred. Jenny had a very natural style – very intuitive. Fred was more cultivated, having had years delivering “emotional truth” day after day on Wonder Years. And their blend of styles was very effective. Haley was supposed to rattle Corey’s cool centre. And Jenny’s street smarts as an actor – and her loose, natural style really helped capture that energy.

Luke Edwards: I don't want to say too much about it, but Fred Savage at that time was a very big deal – and he knew it. It was wonderful to have Jenny there for support.

What does it feel like to have (unwittingly) launched the career of Toby Maguire?

Todd Holland: I couldn’t be more proud. (Actually, I had no idea he was in the film until years later). I just wish I’d kept his home phone number. I could use a friend like that!

Luke Edwards: I was as surprised as anyone when I was told he had a part in the film. I had to go back and watch it again to investigate, and sure as hell, there's little Spider-Man.

Todd Holland: Seriously though, I loved my cast. We really had fun together. We had one moment in the Woods family home when I had all these really talented adult actors dealing with a scene of family tension – and trying to make sense of writing that was geared for a kids movie (and thus not as dramatically demanding as it might have been) and they all turned to me – Beau, Christine, Christian, Sam, Will – and they said: “Someday we have to do a real movie together.”

We all enjoyed each other so much that they just wanted more to do, more drama, more acting... more stuff. That was a nice moment.

The Title Role

Todd Holland: Luke did a great job. And it was not an easy role. And the back-story of his character was so complex – and frankly, dark. A boy whose twin sister had drowned before his own eyes? Half-brothers with Corey, but separated after his Mom’s second marriage ended in divorce? Yikes. That’s a mess for a 9-year-old to process. So I just tried to keep things simple – put the scenes in kid-relatable terms – and help Luke find the end result without necessarily understanding the entire emotional context of the scene.

Luke Edwards: I remember always having the ability to access emotion easily, which is still the case. I've always been the very sensitive type, which serves me in my pursuits as an actor but doesn't serve me very well in many other hard life experiences. It's always a trade-off, I guess.

As far as that specific character, he was a very introverted type, which I naturally was as a child. So, in many ways, I didn't have to work too hard to inhabit that person. Also, I have only one sibling, my sister Malaika, whom I'm very close to and who is incredibly important to me, so I had some real-life connections to draw from.

As with so many film and TV roles that come around, I think you either are that person, or you're not. There's so much to be said for hard work, talent and flexibility as an actor, but most of the time, the roles that come your way do so because of luck. You just happened to be the right person in the right place. I suppose I just happened to 'be' Jimmy Woods in 1988.

"I Love Power Glove"

Todd Holland: Those were more innocent times. And the irony is, saying that the times were more innocent is to say it was still “news” to have a movie embrace such crassly commercial elements: “Fred Savage and Nintendo – two things Kids love. Let’s put them together and make a lot of money.”

Today, no one even blinks at Transformers being a wall-to-wall GM commercial. We expect on-screen characters to be drinking Coca-Cola and using Apple computers. We expect Jack Bauer to dial on his branded phone. That’s just the way everything is done now. But that kind of product placement was news then.

Nintendo was cooperating fully. They had products they wanted to promote: Super Mario 3 and the Power Glove among them. But it wasn’t like we had to say yes – but we weren’t complaining, either. These products fit nicely into our script. We were, after all, a video game movie. So, much like those GM cars in Transformers, we were a good fit with Nintendo. And no, they never told us to change the script in any way.

Nintendo got me started gaming during production — when they gave me my own Game Boy!

It could be argued that without The Wizard, few people would even know that the Power Glove controller even existed. Did Nintendo ask for this device to be given its own scene?

Todd Holland: No... But the Power Glove was big news. And it was a no-brainer to put it into the spotlight – especially to empower our slick villain, Lucas, and put our heroes at a disadvantage to his greater skill, knowledge and experience.

It's not like it is today when you have exclusive access to products. I remember the security guy showing up with the Power Glove in a locked briefcase when we got our first look at it. I liked the idea so much that I gave the character Lucas Barton a similar case. When we shot, the security stood by all day and took the Power Glove away when we wrapped. There was no way they were leaving it lying about on the set.

Scouting And Shooting

Todd Holland: The small town in the film where the Woods family lives was Fallon, Nevada – a very small town. What was hilarious is that in the “prep” stage of the film, we went to Fallon, and I wandered over the “general store” of sorts. I’m not kidding. It was like you see in a movie, with these old locals hanging out on the porch. And I smiled and said hi. And they smiled back. And one old guy speaks up, and the first words out of his mouth are: “Scouting locations, are ya?” And I did this double take because I realized how film-savvy these folks really were. Clearly, we were not the first film to roll into Fallon.

From Fallon, we travelled to Reno – shooting roadwork all along the way. That was what made the film so exhausting to scout – you couldn’t sleep in the van because every piece of road between one location and the next was another possible location.

All the casino stuff was in Reno. Then we flew back to LA and started in the desert outside of town – like Acton, California, where the little airport was where the kids met Lucas for the first time. Then Universal Studios, of course, and Video Armageddon interiors were all shot at Cal Arts University in their big “modular” auditorium.

Were there any especially troublesome moments during the production of this film?

Todd Holland: Shooting in a casino with kids was a real problem. I think it was against the law to have minors in a casino or something, so we arranged to have an empty corner made available to us. And we had to bring in all our own equipment to create the video arcade adjacent to the casino area. But the morning we arrived to shoot, it was like someone had just dumped off two dozen video games and walked away – they weren’t arranged in any way. So we took the first few hours just “building” a set to shoot on – and then we still had to make a really difficult day.

Universal Studios wasn’t a picnic, either. There is one rule at Universal to this day: nothing stops the trams. So, if you’re shooting, you stop to let the trams through. Major pain. We did get access to King Kong for two entire nights – the problem was, of course, that the kids couldn’t work all night. So, that shooting had to be very carefully planned.

Overall, the biggest problem was that the script was way too long. I argued with my producers and finally with the studio that we were shooting way too much movie, more than we could ever use – and that just makes everything harder and costs more and is incredibly wasteful. But I was a young nobody, and I lost the argument and was told flat out by Universal to shoot the entire script. Well, I had the last (sour) laugh. The first assembly of all the footage was two and a half hours long. I ended up cutting an hour out of the film for my director’s cut to reach a length suitable for a family film.

What subplots or key scenes do you immediately recall when you think of the lost hour of the film?

Todd Holland: Without a doubt the keenest memory was of Corey's three friends — Garrett, Bogdanski and Mitchell. Most of the missing footage is at the start of the movie, with more emotional stuff setting up Corey's home life and friends. The kid actors who played these roles did a good job — but it was a no-brainer that all this set-up had to go once the editor's cut came in at two and a half hours.

I wrote the actors each a letter and told them what was happening – that they did good work. The film was just too long. I didn't want them to anticipate seeing themselves in the film – they are 100 percent gone. I thought it was the kindest thing I could do; I mean, Kevin Costner was completely cut out of The Big Chill. It happens in films. You just want to treat actors with respect when it does, especially young ones.

The Big Reveal And "Video Armageddon"

How did it feel to be tasked with bringing the revolutionary Super Mario Bros. 3 to the eyes of the masses for the first big reveal?

Todd Holland: We didn't know what game we were going to be featuring when we started. Super Mario 3 came in while we were prepping — it was super top-secret. And as a non-gamer then, I really only wanted to understand how to play it — so I could direct it. I wasn't that aware of what an "event" that game's release would be to the gamer audience.

I said when I was “selling” myself to Universal to direct the film – “I hate video games. So I’m the perfect director for it. If I can make these video games interesting to me – I can make them interesting to anyone”. And in many ways, I still believe in the logic of that argument.

In the original script, there was sort of a general descriptive of “They enter the Video Championship” – in the classic Hollywood: “and then they fight” shorthand kind of way. And that was never enough for me. I was a huge fan of Aliens at the time – and I concocted the whole Video Armageddon concept with a production design as close to Aliens as I could muster on my puny budget. I still love the image of that last giant door opening and little Jimmy appearing when you thought all hope was lost.

I was driven to make the competition really exciting and accessible. It was written as being in a hotel meeting room, essentially — more "real world" for the period. I saw it should be bigger. I definitely saw this as a big spectator sport — even way back then.

Luke Edwards: Multiple times, I was promised a copy of Super Mario 3 by the producers of the film. I don't want to name any names, but that copy of Super Mario 3 never arrived. Being a big Nintendo and Mario fan, I was not happy about that turn of events!

Studio Battles

Did you make any changes to the script you were given?

Todd Holland: I liked the script when I first read it. But I always want more. More emotion. More Action. More Character. More Comedy. So yes, I pushed for a lot of changes.

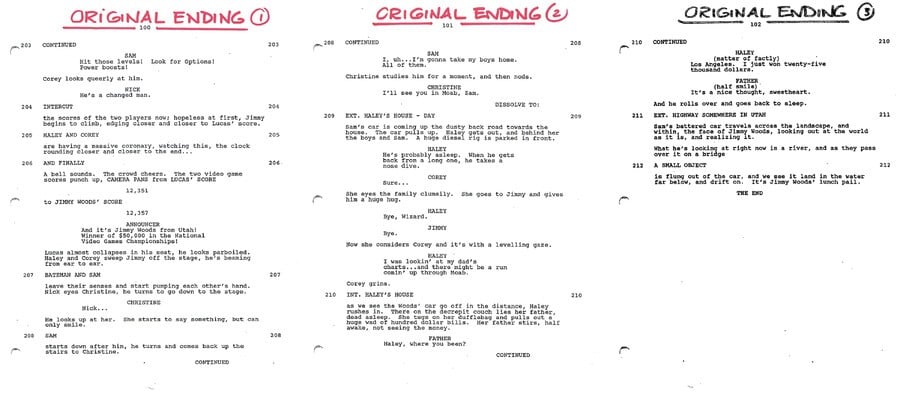

The single biggest rewrite I pushed for (and won) involved Jimmy's whole story of wandering aimlessly and tied directly to the emotional catharsis of the film’s ending.

In the original script, Jimmy wanders for no reason. He never says anything to anyone. And the whole notion of travelling to California is Corey’s idea; Corey is a kind of dreamer, always pondering exotic places he would never really go to – very much like George in It's A Wonderful Life.

My rewrite was all about emotion. I wanted Jimmy to be wandering with a secret purpose that meant nothing to anyone for most of the movie. I suggested that Jimmy say “California”. And that no one would know what it meant. But when Corey hears “California”, Jimmy actually gives Corey the idea of going there. And this mysterious emotional agenda sets the whole story in motion.

In the original script, Jimmy wins the competition and gets to go home with Sam, Nick and Corey – and somehow, I suppose just by virtue of having won the championship – poof – his grief and trauma was supposed to be all cured and everything. There was actually a line of description that explained that on the road home, Jimmy heaves his lunch pail (holding all his dead twin sister’s memorabilia) out the truck window, and it lands in a river and floats away.

I was outraged. I mean, really? A river? The whole story is about a boy who is so deeply traumatized from watching his twin sister drown in a river that he becomes semi-vegetable – and this is how it ends? He throws her “remains” into a river?!

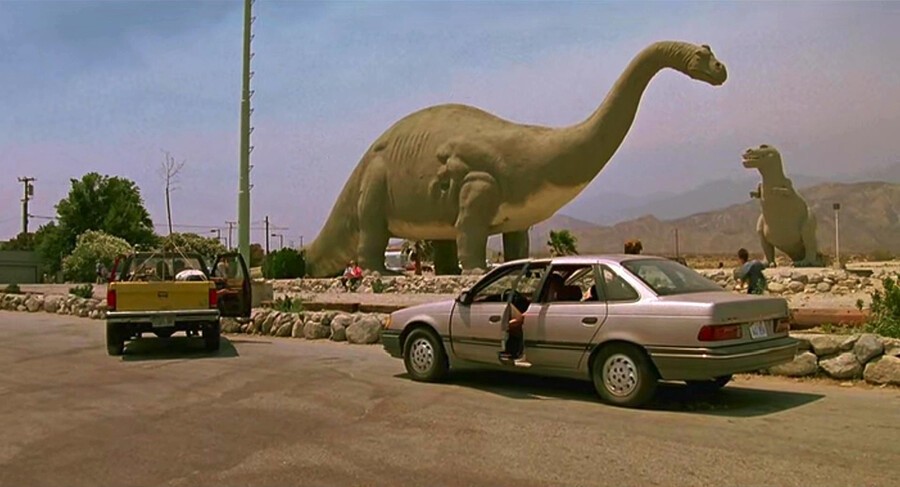

I knew that had to change. So, connecting the dots of the “California” mysterious agenda that I’d started – I pitched that maybe Jimmy knew exactly where he wanted to go all along. And that what he really wanted was to take his sister’s remains – that lunchbox full of her stuff and pictures of their family — back to the last place he could remember them all being happy together.

And I pitched that that place be those Dinosaurs on the 10 freeway outside Palm Springs. And within that dinosaur, the family would learn the truth and come to a new understanding and appreciation of Jimmy – not as a deranged semi-vegetable – but as a deeply wounded boy desperately needing to do one last sweet thing for his dead sister in order to find closure for his grief. And from this emotional catharsis, all their wounds as a broken family could begin to be rebuilt.

Well, I won that argument. The writer bought the pitch – and we ‘sold’ the rewrite to Universal. But along the shoot, my relationship with the producer and Universal fell apart. I’d argued loudly that the script had to be cut – and I’d lost. And from there our relationships all went downhill. It was one fight after another. And the whole film really broke down into “us” (meaning me, the cast, and the crew members that I had hired) and “them” (the studio, writer, and my producer and whatever crew he had hired – or convinced me to hire.) It got ugly. And there was enormous mistrust all around.

And on one of my most stressful days of shooting – on the Universal backlot while the kids were leaping onto the trams and crawling car to car to get away from the bounty hunter – my producer came to me and said, “The studio doesn’t want to shoot the Dinosaur ending – and they want to cut all the ‘California’ references out of the film”.

Now mind you, I’m shooting stunts with kids, and the sun is setting, and I have this crazy schedule to keep, and I’m as stressed out as possible. And I just about had a stroke. I said no. I said that’s crazy. We’ve shot three-quarters of the film shot with all these references to “California” – and if we don’t shoot the ending, then all of that is going to mean shit – and it’s got to have been cut out. So, I said.... let’s shoot the Dinosaur ending, and if it doesn’t work, fine, we’ll cut it all out of the movie at one time. But it’s crazy – just fucking crazy – not to finish what we started at this point.

And somehow – I have no idea how — I won that argument, and we ended up shooting the Dinosaur ending.

Is it true that the powerful final scene was actually written on the spot?

Todd Holland: As weird as it sounds, yeah, it’s true.

Well, if you’ve read the answer above, you’ll be able to imagine the whole political geography of the film by the time we reach those dinosaurs. It wasn’t pretty. I had lost all support with the writer, producer and studio. I was alone. I mean, the writer’s version of my emotional ending in The Dinosaur was included in the shooting script – I’d won that fight weeks before — but it was all too fast and emotionally unsatisfying. None of the emotional beats to make it really build and pay off for an audience were written yet. And none of my entreaties to improve that ending were answered.

I mean, the writer and producer and me – we were just not talking anymore. And so, I wrote that scene inside the dinosaur the night before the shoot. I added all the emotional beats I felt were needed. But the writer and producer wouldn’t publish the changes in the script for the actors – because (I suppose) their instinct was that the Dinosaur shoot was all about serving my ego. So, no one except me was paying much attention to the Dinosaur scene. I don’t ever recall the writer or producer coming inside the Brontosaurus – we shot the interior inside the actual Dinosaur – that wasn’t a set!

So we moved into the brontosaurus to rehearse, and I had the only copy of the revised text – because I had written it the night before – so I just told each actor what to say in rehearsal. And that is what we shot. And that is the ending of the film as it exists today.

The “California” run worked brilliantly with test audiences – and the whole Dinosaur scene was the highest-scoring scene in the film. And Universal, they didn’t care — it’s a business – as long as the film worked, great. There was never another attack on that storyline after my first director’s cut preview of the film.

Luke Edwards: I do remember having the material for the scene relayed to us right before shooting. That was interesting as usually you receive your material long before it's time to perform. I recall a sort of hectic atmosphere for the shooting of that scene, but it came off, I think. For me, Beau really made it work. He brought some honesty to that moment and I've always enjoyed watching that.

The Aftermath

How did the film perform commercially?

Todd Holland: Huge bomb. It cost $6M in its day to make – low budget even then. And it made $13M at the box office. But everyone was expecting that “Fred Savage/Nintendo – how can we lose?” equation to pay off big – so $13M was a huge disappointment. I couldn’t get a job for seven months after that.

It wasn't until the DVD came out — of course, unannounced by Universal — that the internet allowed me to connect with the fans and finally understand that I hadn't failed, and that I did know how to reach my audience on The Wizard. Everything I'd fought to put on film had been really loved and appreciated. But I learned all that on my own; Universal has never reached out to me once in regards to The Wizard. So the battle to get them to treat this film with any part of the love the fans feel for it will be an uphill one. But I'm here and more than willing to comb through the footage if Universal can find it in one of their salt mine film vaults somewhere in Nevada.

One last comment — I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to all the fans who have kept The Wizard alive all these years. It's great to know that with this film we truly reached kids looking for adventure. Thanks for taking the ride.

Creating A Cult Classic

Luke Edwards: It's really wonderful that it has the meaning it does for people.

Overall, it was seen as a failure, which was difficult for me to understand at the time, and of course, this has a profound effect on your professional career. To think about how popular gaming is now and then consider the minimal amount of attention the film received and the money it made in that era is a bit confusing; frustrating, even. But in the end, if the film affected people and was meaningful in their lives, then there is definitely an artistic satisfaction to be felt there.

It's been interesting walking through life, and every so often, you meet someone for whom the film was a big part of their childhood, and you then get to see their excitement and nostalgia when talking about it – that feels good. We were a part of peoples' lives from afar.

There was a screening at the Alamo Drafthouse down in Austin, and Fred and Todd came out to that. It was a great time, and I hadn't seen either of those guys in so long. Todd is such a wonderful guy; he was great to work for then, and he's just as kind and generous now. He's paid me some of the most meaningful compliments I've ever received.

I ran into Jenny probably ten years ago now, and it was a very brief interaction as we were both at a house party (it might have been her house), and she had social obligations, and I was dead drunk. I hope to see her and hang with her again at some point down the road. Jenny was so wonderful to me during production, so it would be great to catch up.