For the avid shoot-em-up enthusiast, CAVE’s incendiary rise and fall was a journey of rare wonder. Rising from the ashes of eminent '80s software developer Toaplan – and consisting of several former employees – in 1995, CAVE tore into Japan’s arcade landscape like a band of unruly upstarts. As shoot-em-up heavyweights Raizing and Psikyo faded from prominence, CAVE reignited the genre with new energy, making an out-of-fashion niche a fashion all its own.

Tsuneki Ikeda – affectionately dubbed “IKD” by fans – joined Toaplan toward the end of its life, co-programming two pivotal titles: Grind Stormer (AKA: V・V) and Batsugun. By slowing down bullet speeds while in turn greatly increasing their number, the sub-genre ’bullet hell’ was born. With Batsugun being the last title Toaplan would produce before its closure, Ikeda would join several of his colleagues at the newly formed CAVE Co. Ltd.

The Birth Of A Legend

DonPachi (1995) and its sequels resurrected Toaplan’s spirit, but with Tsuneki Ikeda’s fresh take: an unbroken aggression shared between player and enemy, screens awash with bullets, and a non-stop, twenty-five-minute stationary form of cardio. Ikeda would quickly rise the ranks at CAVE to become both lead programmer and manager – a rare arrangement in Japan’s typically rigid workplace hierarchies.

Flying in the face of 3D gaming’s all-consuming onset, ESP Ra.De. (1998) started a dynamite string of ever-evolving, increasingly creative works that demonstrated Ikeda and his team’s eagerness to fly close to the sun. Mechanisms became increasingly intricate, pandering to high-tier players and enthralling score hunters with deep methodologies that fostered creative, layered approaches then unseen in the genre. At its peak, CAVE was synonymous with hardcore gaming, becoming its own brand of cool. By the early '00s, they all but owned the distinction.

While an oblivious western mainstream press courted Ikaruga as though it were some kind of sacred artefact, CAVE’s flamboyant pixel-driven hell was reducing the more worldly shmupper to a quivering human coin dispenser. Tearing up the rulebook and assuring their legend to the sound of gunfire, they ushered in a new era of audacious, adrenaline-fuelled violence. From the screen-dwarfing ignitions that accompanied a Ketsui boss defeat, to the unyielding, expert-only hell of Mushihimesama’s Ultra Mode, CAVE games didn’t just cook, they boomed. Morphing bullet curtains and tank-crunching laser beams seduced hardcore arcade goers with edge-of-your-seat highs, and, by the time sadist programmer and ex-Raizing employee, Shinobu Yagawa (Battle Garegga, Recca) joined the ranks to continue his reign of terror with Ibara (2005), Pink Sweets (2006) and Muchi Muchi Pork (2007), the shooting game revival was in full swing. An ailing genre was suddenly transformed into a contemporary beast to which CAVE held the leash.

While Danmaku disciples and intercontinental traders spent years courting Shibuya and Yahoo Japan Auctions for elusive arcade PCB’s – items that now command thousands of dollars – CAVE’s console ports began to filter through to European shores and digital download services. With Arika at the publishing helm, there was rarely a problem, although other ports varied in quality, with Ibara’s PlayStation 2, slowdown-free release probably being the worst offender, and Cave’s own DoDonPachi SaiDaiOuJou Xbox 360 port suffering chronic input lag.

DonPachi (1995)

- Release date

- May 1995 (Japan)

- Formats

- Arcade, PlayStation 1, PlayStation Network, Sega Saturn

A flagship series that would go on to be both the prologue and epilogue of CAVE’s tenure, DonPachi crashed onto the scene with expletive-ridden boss introductions telling you to “Target for the weak points of f**kin' machine”, and a pilot voiceover bleating Top Gun-style calls over the action, not limited to “look out kid, they’re on your tail!” and, “Just a couple more shots!”.

This was the first of many CAVE titles to which art designer Junya “Joker Jun” Inoue would lend his talent. Having previously worked for Toaplan, he arrived hot off the heels of their swan song title, Batsugun, for which he penned the one-shot Manga, ‘Skull Hornets’ – its first printing possibly the rarest shooting game-related book in existence. Inoue would go on to work on many of CAVE’s future titles and is probably best known internationally for Deathsmiles’ Loli-witch character troupe.

Interestingly, according to an interview with Tsuneki Ikeda on the website Spong.com, DonPachi was criticised for being “nothing like Toaplan” on its release, and, ever self-deprecating, claimed the game failed to achieve the team’s goals. Despite this, DonPachi is a blueprint that is as historically significant to the evolution of the bullet hell format as Ikeda’s Toaplan swan songs, Grind Stormer and Batsugun, and Shinobu Yagawa’s Recca (1992) for the Famicom.

It marked a pure beginning for the company, introducing formulas that would be greatly expanded upon in years to come: five stages, two-loops, suicide bullets (aimed swarms released from destroyed enemies), giant mechanised war machines, three ship types, score-based rank increases, a true last boss, and a deep scoring system. Key to Ikeda’s design ethos, and elements that cemented CAVE’s unique feel, is a tiny player-ship hit box weaving through bullets with similarly small hitboxes – often comprising just 20% of their total diameter.

This hitbox harmonisation simulates a feeling of endless accomplishment, encouraging the player to fearlessly thread the maelstrom head-on, creating an illusion of endless near-misses and survival against all odds. At the same time, thanks to the density of the bullet curtains and semi-aimed, constantly morphing mathematical patterns, the hitbox arrangements don’t diminish the overall difficulty. You might dodge a set by the skin of your teeth, but the next test is always just a moment away, forcing you to figure eight around the screen or dive into the storm for score and chaining purposes.

DonPachi felt fresh on arrival. Targeting enemies off-screen as their shadows appeared, learning chaining routes, and using your laser ‘aura’ as a defensive tool were new and interesting features. The blade-like feel of your weaponry, temporarily slowing your movement in return for greater power, gave DonPachi an edge, and informed of things to come.

It marked the launch of CAVE’s first version of their bespoke arcade board, the CAVE 68000, which was used not only for the first generation of in-house titles but licensed out to several other developers, including Kaneko for Air Gallet, a title that promised to “blow your socks off”.

In an interesting piece of trivia, the Hong Kong release of DonPachi was rank-adjusted to the point of brokenness, with bullets almost too fast to see. It was considered impossible to finish, until, after twenty-six years, its two loops were finally cleared on a single credit by Plasmo, a European shooting game super player, using a strategy of 'suiciding' ships during the second loop to marginally decrease the rank.

Above all else, DonPachi marked the introduction of the now legendary Engrish disclaimer on start-up, stating that breaches of legality would be “prosecutedt to the full extent of the jam”.

DoDonPachi (1997)

- Release date

- 5th February 1997 (Japan)

- Formats

- Arcade, Mobile, PlayStation, PlayStation Network, Sega Saturn

DoDonPachi is one of the series most beloved entries, finessing the formula and composition of its predecessor into a more consummate affair, with increased bullet counts and more immediate action. The lasers are bigger, the bomb types more satisfying, the soundtrack and audio blisteringly upbeat, and the pixel art some of the best the company ever produced before it later switched over to partly CG-rendered sprite-work. DoDonPachi streamlined the score-chaining system and the condition-based two-loop run, ultimately pitting the player against Hibachi, a gruellingly-tough true-last-boss mecha-bee with bullets almost too fast to read.

DoDonPachi also began CAVE’s dedication to visual feedback and reward, lighting up the screen with giant, trafficking lasers and shiny point bonuses. This experimentation would peak in the ESPGaluda games, where a successful Kakusei or Zesshikai cash-out erupts so spectacularly that it causes graphical glitches in the overload. DoDonPachi’s slowdown and, in turn, its exploitation was a strategic feature, intentionally added into all of CAVE’s future releases. Replication of accurate slowdown for home ports became a sticking point with fans, its varying results and outright failures key to their quality.

Like its predecessor, the bee theme remains instrumental, and hidden medals tie chains together to ramp up score. Scoring well, in turn, increases rank considerably throughout the campaign – although in spite of this, DoDonPachi’s first loop is one of the series easiest to one-credit clear.

A stunning piece of work, it cemented CAVE as one to watch, and spearheaded the shooting game revolution in its new bullet hell form.

DoDonPachi II: Bee Storm (2001)

- Release date

- May 21st, 2001 (Japan)

- Formats

- Arcade

DoDonPachi II: Bee Storm wasn’t developed by CAVE, and its legacy isn’t as glowing, aping the bullet hell style with enjoyable but somewhat crude results. Developed by Taiwan’s IGS (who these days develop popular driving games in Asia), the story of how it came to be and how it affected CAVE’s future is the most compelling aspect of its history.

At the time, CAVE were six games and four years on from DoDonPachi, and their most recent effort, Progear no Arashi (2001, for Capcom) signified a string of steadily declining sales as the arcade market was usurped by the home console boom. IGS had developed a new arcade hardware platform, the Poly Game Master – or PGM – and obtained the DonPachi license to create a game for the system.

Against all odds, and despite its unpolished finish, DoDonPachi II was a hit, convincing CAVE to both stay in the market and to adopt IGS’s PGM hardware for their future titles. Interestingly, many original ideas that surfaced in IGS’s black sheep title were picked up on by CAVE and can be seen, in a form, in their later titles. And, fortuitously, DoDonPachi II resulted in the production of both what many consider the greatest CAVE title of all time, and one of the greatest games ever made: DoDonPachi DaiOuJou.

DoDonPachi DaiOuJou (2002)

- Release date

- 5th April 2002 (Japan)

- Formats

- Arcade, PlayStation 2, Xbox 360, iOS

Tsuneki Ikeda’s magnum-opus, DoDonPachi DaiOuJou (or “Peaceful Death”), was, according to an interview featured in a booklet that came with the game’s console port, partly inspired by Treasure’s Ikaruga. Haunted by the idea that they could only ever create something lesser, Ikeda felt CAVE could never live up to the ‘genius’ of Treasure’s work. He was wrong.

Trouncing Ikaruga in almost every respect, DaiOuJou has become the most revered game in CAVE’s canon. It is, quite frankly, an unparalleled bullet hell masterpiece.

Within its bombast is a work of art: a leaner, wholly more aggressive affair than its predecessors, with a tightly honed equilibrium. Its longevity is astonishing: one can dedicate hundreds of hours and continue to learn, finding new chaining methods or stage routes, creatively manipulating the chaos.

It teases you with its savagery, but pays out dividends when you begin to snatch back milestone victories. Inside its mathematically structured bombardment is a euphoric fissure, a power trip that never gets old; and, before you know it, you’re hopelessly addicted, seduced by cathartic hostility set to a timeless Manabu Namiki soundtrack.

Deciphering seemingly indecipherable patterns, tipping the scales in your favour, and twisting the game like the iron bar that it is, is joyous. This near-matchless level of videogame rapture is down to the fineness of its composition: adrenaline highs as uniform as the blitz itself. The ‘aura’ around the ship’s laser, a protective shield from popcorn enemy collisions, also encourages point-blanking, the art of getting up close and personal with bosses and large enemies to deal extra damage.

Its massive, screen-ripping hyper lasers are both purgative tools of death and ties that bind the carefully crafted chaining system together, ramping up score and sending combo strings into the stratosphere. Its second loop, upping the ante with rampaging suicide bullets and an insane true last boss, is the stuff of legend. It’s a game that exists in two forms: the original, and the limited edition Black Label variant (the first of many Black Label augmentations CAVE would release). While Black Label makes the chaining fairer, slightly easier, and the hyper medal drops more plentiful, the absolute hardest of the hardcore hold the vanilla version aloft as the purest distillation of its dovetailing beauty and brutality.

When the player becomes one with it all, bleeding Hypers fearlessly and urging the stakes higher, bending to the flow of bullets and hitting full stage chains – the sound of extends more rapid and medals raining down as icons of empowerment – then, and only then, can you really appreciate the magnitude of the achievement.

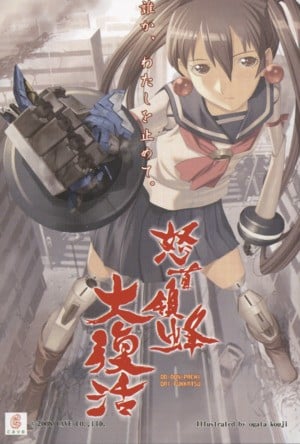

DoDonPachi DaiFukkatsu / DoDonPachi Resurrection (2008)

- Release date

- May 22nd, 2008 (Japan)

- Formats

- Arcade, Xbox 360, iOS, Android, Microsoft Windows, Nintendo Switch

Considered by many to be the in-house black sheep of the series, DaiFukkatsu (known as DoDonPachi Resurrection in localisation) introduced a divisive mechanic: the auto bomb. With Mushihimesama spearheading optional difficulty levels in 2004, and the kid-friendly routes of Deathsmiles attempting to coax newcomers, DaiFukkatsu was a game that followed four years of experimentation. Not content to go back to the series purely aggressive roots, the catering toward a broader spectrum of arcade-goer made DaiFukkatsu somewhat exploratory. Three ship types with optional styles of attack changed the way the game behaved. Bomb style was aimed at beginners, auto-bombing in the event of a collision, while Power style replaced the bombs with an upgraded laser appendage and a tougher run.

The first iterations of DaiFukkatsu became lost to time, now only accessible via emulation. In its early location tests, the ordnance spewed by enemies, specifically the shape of its lasers, looked different from the final product, among other oddities. The 1.0 version, on full release, was quickly removed from arcades owing to bugs and scoring issues that would be reworked in the 1.5 revision, and later a Black Label variant of the game. These updates tweaked and fixed a lot of the game’s unevenness and added the ‘Strong’ style play option that was only accessible via secret code in 1.0.

The convoluted ship variations and hyper-rank management made the game difficult to fathom initially, splitting scoreboards and dividing opinion. It’s a stunning-looking affair, and deep as they get, either allowing rookies to skim the surface and enjoy demolishing the landscape, or the existing hardcore to dig deep, exploit scoring tricks, and follow the secret ‘Ura route’ – a dazzling time warp that allows you to battle mid-bosses from DonPachi history.

It’s also perhaps the most visually bombastic of all of CAVE’s efforts, an orchestrated chaos filled with endless, thundering explosions, and, thanks to its ‘hyper counter’ mechanism, bullet-to-point conversions and laser duels that bleed collectable ingots.

Despite having one too many iterations, it’s now better understood by the shooting-game fraternity, and is the entry that resonated most internationally thanks to its home and mobile phone ports and ease of entry for survival play.

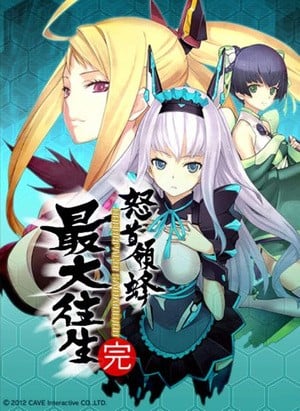

DoDonPachi SaiDaiOuJou (2012)

- Release date

- April 20th, 2012 (Japan)

- Formats

- Arcade, Xbox 360

The end of all things, SaiDaiOuJou (“Angry Leader Bee True Death”) was the swan song for the CAVE we knew and loved. It was both the last entry for the series that started it all and the last time the company would release an original shooting game in arcades. It had been a seventeen-year journey of unexpected arcade magic, a reinvention of a genre, and one of the most quality-consistent outputs ever from an independent developer. It wasn’t just the end of CAVE, but in many ways marked the end of the arcade, the industry’s cavernous remains repossessed by redemption machines and K-Pop dancing tablets.

SaiDaiOuJou returned to CAVE’s roots, somewhat, simplifying the formula significantly from DaiFukkatsu for a more back-to-basics affair. It bears many structural similarities to DoDonPachi DaiOuJou: Three ships piloted by three elemental dolls, and an emphasis on dodging rather than cancelling.

It had a long, slightly troubled development, came with an overflow bug that allowed players to achieve scores never meant to be, and has a visual style that’s an unusually clean sci-fi departure from previous entries. At the same time, it’s absolutely glorious. It’s the only game in the series that removes the two-loop structure, instead beckoning the hardest of the hardcore to attempt to reach one of two true last bosses by meeting specific conditions. Fighting Hibachi here allows only one death and requires at least three stages of perfect bee medal collections; while Inbachi, the most formidable boss CAVE have ever created, requires no deaths, no bomb usage, all bee medals collected across all stages, and rank and combo requirements depending on the shot type used. It took almost ten years before Inbachi was finally defeated (in training mode) by player IFC-Sairyou.

SaiDaiOuJou doesn’t quite pip DaiOuJou in terms of pureness and out-and-out perfection – but comes wonderfully close. Its five stages of unrelenting, adrenaline-fuelled hell tell stories within stories. The landscapes, enemies, and overlapping bullet patterns evolve constantly and beautifully, requiring you to constantly adjust your approach from one section to the next. To quote another famous shooting game, there’s a fissure of consciousness within its intense, unrelenting five-stage barrage that occasionally reaches unprecedented highs.

SaiDaiOuJou was a near-perfect way for CAVE to bow out, both in arcades and on home consoles. The superb Xbox 360 port came stuffed with original modes, optional bug fixes and other delectable treats, but was sadly hamstrung by a chronic input lag that was eventually fixed with a fan-made patch.

The End Of The (Bee) Storm

CAVE’s body of work is beholden to a pureness in design ethic that few video game companies ever achieved with such consistent quality.

Although the shooting game has always intertwined survival and scoring to some degree, CAVE somehow made these two processes both completely separate and, at the same time, holistic. The depth of thought and arguably convoluted scoring extremes are what keeps the gaming community returning today, a decade after the company’s demise. To play a CAVE game purely for survival is an immediate, engrossing experience in which the player can connect with the rawness of it: twitch-dodging, dropping bombs, navigating the endless minefield, and edging out a one-credit clear.

But, when toying with the scoring elements, slowly grasping an understanding, and then exacting a fresh plan on each subsequent play, the anatomy morphs, often into a game you feel like you’ve never played before.. The reward for your effort is, on the one hand, increased life extensions and on the other, increased rank. It’s a beautifully balanced exercise that consumes the thought process, and beyond the basic reward of survival, consistently provides an adrenaline buzz through visual feedback: huge score ingots, end-of-stage calculations, and the feeling of getting it right.

From the more abstruse scoring of Mushihimesama and its sequel, to the stringent chaining processes of DoDonPachi, to the glorious overkill of ESPGaluda II’s dice with death, CAVE games play like few others ever have, and ever will again.