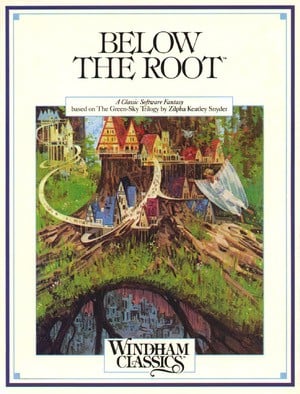

Released in 1984 for Commodore 64, IBM, and Apple II, Below The Root is an expansive, free-roaming, open-world platforming adventure featuring a LucasArts-style command list, progression mechanics reminiscent of Metroid et al, plus light RPG overtones – yet it predates Maniac Mansion, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night and Metroid.

Players can level up to attain new abilities, buy and sell equipment, talk to NPCs and read their thoughts (pense), psychically modify the environment in real-time to pass obstacles (grunspreke), glide through the air, teleport objects around the screen (kiniport), and later even teleport themselves. There's a day/night cycle, a need to eat and rest, multiple playable characters with differing abilities (male, female, child, adult), and an enchanting fantasy setting to explore.

It was the canonical follow-up to the Green-Sky trilogy of books by renowned author Zilpha Keatley Snyder, and she was actively involved in the writing and design. Thus, it represents one of the earliest and best examples of "transmedia" and the potential of games as a creative medium. Think of your favourite book (or film) – now imagine, not just a cheap or generic licensed tie-in, but something richly detailed where you can interact and explore beyond the linear page, immersing yourself and truly becoming part of it.

Below the Root excelled not just within the grand compendium of games for 1984, but also as a licensed work offering an experience only a video game could provide. Certainly the public thought so; a cursory search online reveals innumerable fans who don't merely remember it fondly, they adore it and cite it as a defining influence in their lives. Glancing at the comments on Lemon64 alone reveals plenty.

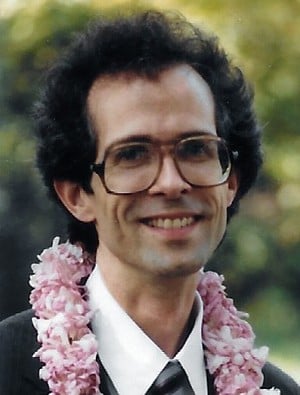

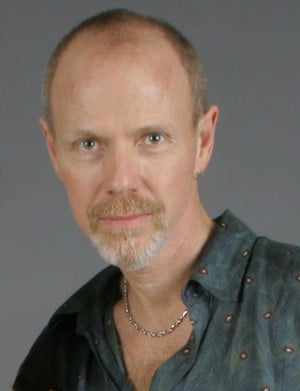

Would you believe this timeless masterpiece required only three core staff? Snyder, as already mentioned; Dale DeSharone (formerly Disharoon), acting as programmer and co-designer; and William "Bill" Groetzinger as the graphics artist. (Others also helped program the conversions from the C64.) Sadly, DeSharone passed away in 2008, his only interview having been done by your author. Snyder, meanwhile, passed away in 2014, while Groetzinger seemingly moved out of the industry sometime in the mid-1980s. Documenting this game might have seemed impossible, were it not for one man.

Enter superfan Justin Stahlman – a stonemason by trade, he also writes music, paints, produces animation and makes video games. Most significantly, he has actively worked to preserve the legacy of Below the Root, describing it as a lifelong obsession and inspiring his art and programming. Previously, Stahlman had mapped the entire world, written extensively, documented the hidden level editor, plus spoken with both Snyder and Groetzinger about remaking the original for modern platforms. In turn he introduced your author to Groetzinger and encouraged the feature you're reading right now.

To understand the making of Below the Root, we first need to explore how both DeSharone and Groetzinger came together from backgrounds in education.

An Unlikely Origin Story

"My major in college was film and video production," said DeSharone in our aforementioned interview, explaining the build-up to game development. "I always had an interest in the production of entertainment products, but I wanted to work with kids. So I got into teaching and taught for three years. This was at the end of the '70s, when home computers were coming on the scene. That was when the Apple II made its appearance, and the Atari 400 and 800. The principal of the school wanted to get computers, and I didn't know anything about them, and I wanted the school to get woodworking equipment. But she was the principal, so she got her way. She took me to a programming workshop that Radioshack was giving. When I saw the possibilities of computers, in terms of presenting visual information, I was very excited about it. We ended up getting Atari computers for the school, a couple of them, and I got one myself, and taught myself to program. I just sort of fell into it by accident. I started writing things for the kids in my class; educational games. At that time the Atari Programming Exchange had quarterly submissions and publications, with prizes. I submitted a couple of my educational games, and they won the first and second prizes of the quarter they were submitted. So I won about five or six thousand dollars worth of computer equipment from Atari."

This windfall of equipment would help DeSharone launch his new "accidental" career, which then dovetails with Groetzinger's story.

"Before meeting Dale Disharoon, I didn't own a computer," admits Groetzinger. "I didn't even know that games for computers existed. I enjoyed illustration and cartooning, usually with pen and ink or pencil drawings. I had earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts with a major in graphic design from Ohio University in 1971. I was employed as a commercial graphic artist in Ohio, from 1971 to 76. I served on staff at Maharishi International University from 1977 until 1981. When I met Dale I was a freelance artist living in Fairfield, Iowa. Dale saw me drawing people's portraits at a 'street fair' on the campus of Maharishi in the early 1980s. He introduced himself to me later and proposed that I work with him to create pixel images to stand for each letter of the alphabet."

This chance encounter while Dale was in Iowa would lead to Alphabet Zoo across a variety of formats. But, as DeSharone described it, the encounter almost didn't happen. "After the third year of teaching, I stopped. I had actually wanted to continue, but I was half-time, and they wanted a full-time teacher. So, I thought I could probably at least make as much money making games, as I was teaching. Which was more than true! I hooked up with Spinnaker at that point, and wrote some early educational games for them. Alphabet Zoo, Hey Diddle Diddle, and another called Adventure Creator. I guess that's the point where Below the Root started."

Groetzinger wasn't involved in the latter two titles mentioned, only Alphabet Zoo – but what's interesting is his role was strictly creating artwork on paper for DeSharone. It was also done remotely. As Groetzinger recalls: "I worked from home, my apartment, in Fairfield. I drew an apple for the letter A, a bear for the letter B, some candy for the letter C, and so on. One image would appear in the centre of a small maze while the letters needed to spell out the word for the image would randomly appear inside the lanes of the maze. I also created a half dozen animated sprites. A child could select a sprite to guide through the maze using their computer keyboard or joystick to 'capture' the letters in spelling order to spell the word they saw pictured in the maze-centre. It was a race to do it quickly. Two children could play against each other or one child could play alone. I worked as freelance for Dale. He paid me by the image and I supplied him with coloured pencil images on graph paper."

After leaving teaching, DeSharone founded Dale Disharoon Inc., his California-based development studio which created games for Spinnaker and The Learning Company, plus a few books for Prentice Hall. Mostly, it focused on software for computers; the Atari 400/800, C64, Apple II, and IBM PC. Interestingly his company also did Atari ports of a few Strategic Simulations games, such as The Battle of Shiloh and Battle for Normandy, though these are erroneously credited to Tactical Design Group. All this continued until around 1987 when DeSharone moved to Boston, Massachusetts, to work for Spinnaker, ushering in the Philips CD-i era of his career. It was during the West coast period when Below the Root came about.

"So I was in Northern California," DeSharone said, explaining, "The author of the books, Zilpha Keatley Snyder, lived about an hour's drive from where I was living and working. So I went to visit her, I showed her what computer games looked like, she became very interested in the possibility of collaborating on a game. We worked very closely then on the design of the game, based on the books."

While we sadly can no longer interview Snyder, browsing her website on the Wayback Machine reveals some nice anecdotes, where she explains: "The computer game transpired when I was contacted by a young computer programmer named Dale Disharoon. After Dale introduced me to the world of computer games, I wrote and charted, Dale programmed, and a young artist named Bill Groetzinger made marvellous graphics for a game that takes off from where the third book of the trilogy ends."

Needing an artist DeSharone would call on Groetzinger again, this time though it wouldn't be remote work using graph paper. Comments from the various people who knew DeSharone reveal a kind-hearted colleague of warmth and empathy (he actually taught one of his employees to drive). In this instance, he invited Groetzinger to journey over 2000km and live with him in his home as they worked on the game. The scenario speaks not only to DeSharone's character, but the zeitgeist of 1984, when just two or three people could create something wonderful together.

"Dale called me on the phone," recalls Groetzinger today. "I still lived in Iowa, while he lived in California. I don't believe I met Zilpha Keatley Snyder in person. Dale met with her before I was brought onto the project. I had previously read all of Ms Snyder's books in the Below the Root trilogy series; I was already a fan of science-fiction. Dale told me that Below the Root, the video game, would continue her story into a 'fourth book' so to speak. When I began work on it, probably a year after Alphabet Zoo, I flew out from Iowa to California and lived and worked out of Dale's apartment in Santa Rosa for the first 2~3 months. Later, he moved into a new home he bought in Chico, CA. After he moved, I found and rented a room in a house a few blocks from Dale's new home. I was able to walk to 'the office'. He set up a computer and table for me inside his home, the same computer from Santa Rosa."

An Underrated Fantasy Trilogy

At this point, it's worth examining the books themselves; don't worry, even if you've never read them, the game is still accessible. Snyder, on her website, gave an account of the inspiration: "Like so many of my books, the trilogy's deepest root goes back to my early childhood when I played a game that involved crossing a grove of oak trees by climbing from tree to tree, because something incredibly dangerous lived 'below the root'. Years later when I was writing The Changeling I recalled the game, and in the course of embellishing it for that story, became intrigued with the idea of returning to the world of Green-Sky for a longer stay. The return trip took three years and produced three more books. Initially published in 1975, 1976, and 1978, the trilogy was later reincarnated as a computer game."

The trilogy takes place on a verdant world of enormous trees - think the forest world of Endor and its tree-top villages, but with psychic gliding humans instead of Ewoks. Everyone is a pacifist, eschewing the eating of meat, not committing violence, and not stealing. It's peaceful, but a series of events leads to the society becoming divided, and some being forced to live underground and become omnivores again. In a variety of ways the thematic setting weaves itself into the mechanics: if you select a tree dweller, they'll face status penalties for eating meat, thus limiting them to bread or fruit. Players also can't simply take items in NPC's houses, but need to speak with them and be offered an item. It all works well to convey a believable and interactive world.

Snyder also invented a unique language for this world, which again integrates itself into the mechanics: the large trees are called Grunds, and beds are referred to as "nids". (Does this use of a unique language remind anyone else of the later released Panzer Dragoon Saga?) At one point, a wise old woman suggests seeking a "Sky-nid and a dream". One of the especially tall trees is called Sky-Grund, and climbing to the top, which requires some puzzle solving, reveals a lone house with a bed. If you rest for a while, lo and behold you will awaken in the clouds, to communicate with a key character and receive an item.

We raised the topic of the game being faithful to the source material. "Yes," confirmed DeSharone. "She wrote a lot of the dialogue herself, she played with the map, the mapping of the world – we worked on that together. She was instrumental all the way along the process of building the game. It was a lot of fun working with her."

The game's manual has a wonderful letter from Snyder describing the process, showing just how invested the author was. Reading this, keep in mind Snyder was born in 1927, so would have been nearly 60 at the time. Given how much antagonism older generations had to computer games, it's awe-inspiring the foresight and open-mindedness Snyder showed:

I have always loved writing fantasies and adventures for young people, but had never used a computer until I met Dale Disharoon. He introduced me to adventure games on computers, and as I learned about the capabilities of the computer, I saw so much opportunity to adapt my own writing to this new and exciting medium. From the beginning, Dale and I agreed that we wanted a game with story qualities, characters with personality traits that could grow and develop, and an outcome that would be consistent with the storyline of the game as well as the trilogy that came before. We wanted our game to have the best and most artistic graphics possible, lots of action, and some aspects of the eye/hand coordination demands that make arcade games exciting.

With DeSharone guiding Snyder through the technicalities of game design, we asked Groetzinger about the art side and shifting from paper materials to digital. "For Alphabet Zoo I did my drawings on graph paper and Dale input the art manually into the game," he confirms. "I'm limited in my understanding of computer programming, but for Below the Root, Dale created a computer program which allowed me to create and enter my art directly into the computer. He then imported my work directly into his game program. My art was created using the Commodore 64 first. That had the widest spectrum of colours to choose from. Later, Dale translated my finished art, which I'd directly input into the C64 using his software, into data which was compatible with the other computers – the Apple II and IBM PC. The colours suffered a bit from the translation due to having fewer choices. To make the game easy to port I'm certain the resolution was the same for all. Dale hired more programmers to fine tune the additional computer versions. In this way, I think all three versions were available for sale at around the same time."

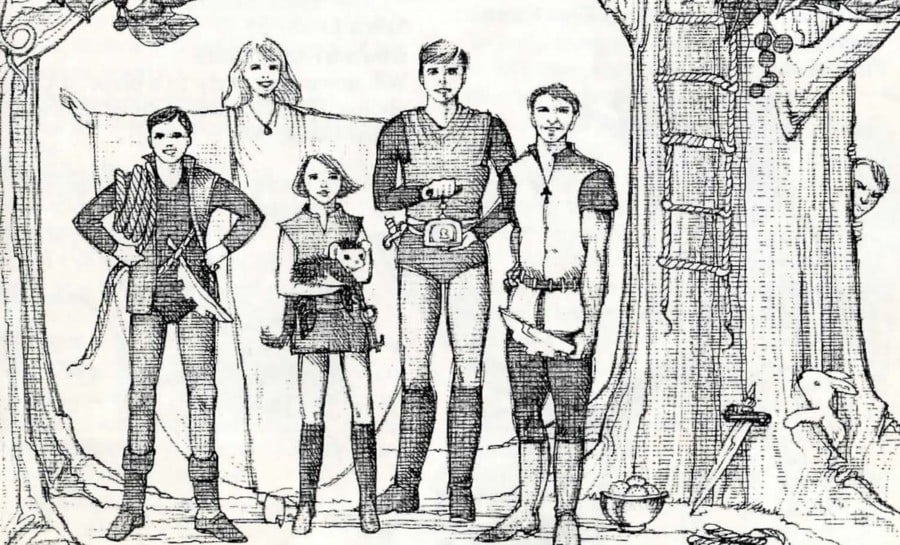

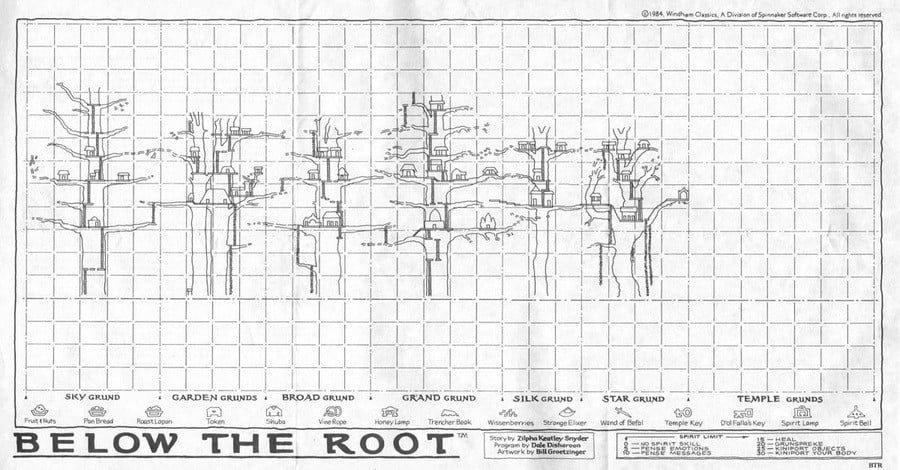

But if Groetzinger and Snyder never met, what sort of asset pipeline did they have in place for production? As described by both, it was DeSharone who synchronised things. "I was offered a very limited vision of the forest world I was to create," begins Groetzinger, elaborating, "I started drawing the central tree – Grand Grund or perhaps it was Broad Grund? – and organically added limbs and branches to the left and right, adding buildings and new trees as Dale requested them. The last building I created was Temple Grund to the far right. A player needed a certain high level of skills to pass through the gateway into Temple Grund. Zilpha Snyder did not work with me directly. She worked directly with Dale, and it was Dale who directed me to create various obstacles and challenges and buildings in order to meet the needs of the storyline. After completing Temple Grund I was directed to work on the underground passageways and how they ended. I did not foresee these passages until I had finished the trees and forest floor."

The game's map is notable, being 32 screens wide by 16; a total of 512 screens, which is more than The Legend of Zelda's overworld of 128 (we realise the dungeons bump this up). Stahlman in fact created a 1:1 map using screengrabs, showing it to be 10,240 x 2,560 pixels. Granted, some of the screens are just empty air up in the trees or inaccessible cavern sections, but it's an impressive feat for the time, fitting on only two disks.

In the manual, Snyder further elaborates on the process:

I began to map out the vast world of Green-Sky on an enormous sheet of graph paper spread out on my studio floor. I sketched the many grundtrees whose intricate network of branches supported the homes, shops, temples, and public buildings of the people of Green-Sky. Then we planned the questers, with their initial attributes as well as the tools and abilities they might acquire. Next came the many inhabitants of the land; I planned the responses they might make when addressed or 'pensed'.

In turn, Groetzinger would realise these ideas when creating the backgrounds. As he explains: "I'd forgotten so much, but seeing the maps again – both hand-drawn and using screens – the sprites, and the original box art, reminded me just how much work was involved. The many backgrounds were created by me, first by making hundreds of 'building blocks' each 8 pixels by 8 pixels. I created all the backgrounds using these building blocks alone. As the number of backgrounds grew, in order to allow me to create different trees, limbs, foliage, house exteriors and interiors, signage – I created an alphabet, 26 letters, numbers 0 to 9, in both white and black – and underground tunnels, I had to create additional building blocks to build more complex screens. I also created poses and animations for each main character so they could walk, run, crawl, glide through the air in a shuba, and lie down."

All of this came together to produce a fun adventure. The ultimate goal was to find and save a key character from the books, with players given a generous time limit of 50 in-game days (you can do it in three). Reading (pensing) the thoughts of NPCs offered clues on what to do next, or if you could trust them. While some offer you to rest in their homes, doing so may result in your kidnapping. You'll awake locked in a house, needing a trencher beak to cut yourself free – but even if players find themselves trapped by a puzzle without a key item, selecting "renew" allows them to waste a day and wake up back at home. The same happens if falling into water, or running out of energy. (You can also do this to quick travel, if you don't feel like walking back.) The only "game over" is by reaching day 51. As such it's actually quite a low stress game, with the main challenge being to explore all those screens.

Perhaps surprisingly, it didn't take all that long to develop. Several months at most, according to Snyder's letter in the manual:

Dale and I worked very closely over many months on the adaptation. While I sketched and charted Green-Sky, he made it all possible by ably programming the computer. Our ideas flowed back and forth, and it felt more like play than work.

Groetzinger described his side, including the daily routine at DeSharone's home. His sentiments echo Snyder's in how enjoyable the project. "As Dale worked on the programming, I would work on the art independently. Each day, he'd upload any new background screens, character animations, and building blocks, which I'd added from the day's accomplishments. It took about four months for me to complete the art. I also helped create the physical map packaged with the disk that allowed players to draw in more trees as they explored the forest and underground. Dale seemed to appreciate the work I did for him. He paid me well as an employee. I enjoyed this work more than anything else I've done since."

When Below the Root launched, it was treated somewhat differently to other games, as reflected in its unusual guerrilla marketing campaign. Which is how Stahlman discovered it. As he recalls: "It was marketed as 'educational' software back in 1984. It was a time of cracked and copied games being shared at school on diskettes, games like Castle Wolfenstein, Conan, Rescue Raiders, Lode Runner, and so on. We kids found 'educational' software so boring compared to the pirated games - except Oregon Trail, that was great. Anyway, at home, I got Below the Root in the mail, unsolicited, as educational software. If you liked it you were supposed to buy it, otherwise return it; marketing sure has changed! I tried it and couldn't believe how vast it was. It was by far the best game I had ever played at the time, and it was unique too. When I was 11 years old that unfinished map was so enticing. I love that Bill helped make the hand-drawn map. That map is not talked about enough. It was a time of Dungeons & Dragons – basically a game of maps and imagination. It was also the era of Indiana Jones. Below the Root had that 'jungle mystery' feeling. A lot of its richness was due to it being based on the books, with the backstory and all the mysterious references to characters and items, the unique names having French and German influences."

While players may have loved it, the question is how many actually bought it rather than sent it back? With only Groetzinger left, we asked if he knew how well it did commercially. "I don't know the real answer," he admits, adding, "It probably was successful. It led to our working on Alice In Wonderland, which used the same game system; it used the exact same technology. Dale found another author, Laurence Yep, to help embellish the Alice storyline. As I recall, the background screens for Alice were more numerous than those I'd created for Below the Root. I started from scratch, making the building tiles to create the background scenery."

His answer raises other points. Groetzinger is credited on the CD-i remake of Alice In Wonderland, given it's based on his original art. Was he directly involved though? Also, with few other credits on MobyGames, where did his career take him? "I'm not familiar with CD-i," he reveals. "I worked on Alice on floppy disk for Windham Classics. This too was made for C64, IBM PC, and Apple II platforms. After Alice, I worked with Dale on Peter Rabbit Reading and on The First Men in the Moon Math, two educational games for children. They worked rather sluggishly on the three platforms, perhaps because the graphics were more complex. These were among the last games I worked on with Dale. After a few years, I don't remember how many, I visited Dale in his home / studio in Massachusetts. His operation had added multiple artists and programmers. I later worked in graphic design in California, Ohio, Massachusetts, and Colorado. And finally, I worked 13 years as an administrative assistant in a Human Resources office in Illinois until I recently retired."

Playing It Today - And In The Future?

By now, we've hopefully enticed you to explore this world too. Ideally, there would be a release on GOG or Steam, or maybe even a remaster or remake. Sadly there is not, though a remake almost happened.

In September 2010, Stahlman contacted Snyder about the rights to remaking the game for iOS. Her response to Stahlman was optimistic, stating: "Let's see, an iPad version of Below the Root? About the publishing rights, I just don't know; Dale Disharoon who did the programming has died, and the Spinnaker Software company who produced the game has gone out of business, so I guess that just leaves me. However Below the Root has recently been optioned by a film company, which may complicate matters. Do you intend to market your iPad version? If so, I'm sure there would have to be some kind of a contract. I guess you might start by contacting my agent."

Stahlman did so, and again the response was encouraging: "The film option is not yet signed so that can be dealt with. The rights to the original game may not be kaput with the death and dismemberment of the proprietors and founders. We'll have to look at the contracts if Zilpha can put her hands on them. It is often a complex business. I'll respond when I know more."

Sadly, Snyder passed away before anything could be finalised, though Stahlman also managed to contact Groetzinger, who gave his blessing for the art being used. Your author made contact with Stahlman, initially not for this article, just to reminisce on the passing of creative people both admired, and to ask Stahlman's permission to reuse his map in an academic lecture. The shared feeling was that one always feels there'll be tomorrow – when actually, there is an urgency to document the memories of developers, especially for games made 40 years ago.

The conversation led Stahlman to make a suggestion. "I know what you mean about thinking you could contact Dale later," he told your author. "Zilpha Keatley Snyder also died before I could talk to her again. Four years after that email exchange, on 7 October 2014, she died. I never did get any more information about the rights, but I kept learning more about games. You should talk to Bill Groetzinger, the artist who made the graphics for Below the Root. I was super happy that my emailing took him down memory lane. Imagine being the guy who made that art with 1984 technology."

Without a remake or licensed release, the only options are legacy hardware or emulation. The latter of which is likely to leave newcomers feeling overwhelmed. While we wholeheartedly encourage everyone to experience this wonderful game, please take a moment to read the manual, which will explain the more esoteric commands and offers great advice. While such a vast game seems daunting and impenetrable, it's honestly fine (this is definitely not Tir Na Nog!). That initial sensation of confusion and awe is the absolute best part – once you know what to do, or cheat with a guide, it can actually be finished in under 30 minutes.

The joy is in living in this meticulously created world, so embrace the wonderment. For a starting character pick Herd, since he's the easiest both in terms of abilities and starting location (two screens directly left is your first key encounter). And make sure you've downloaded Stahlman's map to your phone – or you can print off the retail packaged map and draw it in yourself. The entire world is accessible from the start apart from the Temple area, and the end-game caverns. Oh, and be sure to pense the thoughts of any monkeys and rabbits! Have fun.

In the end, we asked Groetzinger how he feels, 40 years later, knowing that people were still talking about and playing Below the Root.

"I am pleased and surprised to this day when a former high-school friend connects with me and asks if I'm the one who created the screen art for this game. My name is not too common. They often say that they and their children very much enjoyed playing it. At the time, as I was not a fan of computer gaming, I didn't know how it would be received. I only did the best work I knew how to create."

This revelation of parents introducing their children to Below the Root is echoed by others too, including Stahlman. "My niece, age 11, is now the same age I was when I discovered Below the Root," he shares. "I know you can't force kids to like what you liked as a kid. They just can't possibly care about pixel graphics and those old games since they grew up with iPads and the internet. But I tried to make an animated cartoon based on it for Christmas, with my niece and nephew as characters. It was my attempt to let them feel the amazement of Below the Root. More than anything it shows how I'm still obsessed by the game. <laughs> I love the story of how Bill lived with, and later near Dale. It's amazing how Dale found him doing portrait art, not something game-related. I love how games were made by one or two people in the early days. There weren't committees, or big teams like making a movie."

Today the books are still available to buy, at least on Kindle. Sadly the game hasn't seen any official re-release. Have you read the books or played the game? Would you want to see it brought back? Post in the comments if so.

Special thanks to Justin Stahlman for arranging the interview with Bill Groetzinger and for all his work preserving the legacy of Below the Root.