In the late 90s, Rockstar Canada unleashed Grand Theft Auto: London 1969 onto the world. The chaotic joyride through 1960s London wasn’t a full-blown sequel to the original Grand Theft Auto, but a complimentary mission pack that worked in conjunction with the former to bring you new locations, missions, and period-accurate vehicles. As such, it garnered somewhat of a mixed reception upon its initial release, with publications praising its soundtrack and sixties setting while highlighting its lack of innovation over its predecessor.

In modern times, the reaction has started to skew more positive, with the title earning a cult reputation among diehard fans for being one of the few games in the series to take place outside of America (alongside its freeware prequel Grand Theft Auto: London 1961). But have you ever wondered how this quirky expansion came to be in the first place? Or what challenges were involved with transporting the action to the UK? Time Extension set out to investigate. However, first, we had to take a look back at the complicated history of Rockstar Canada and how the studio ended up in charge of the project.

The Birth Of Rockstar Canada

In July 1997, the publisher Take-Two Interactive acquired several assets from the struggling Florida-based publisher GameTek, including the small team at GameTek Canada. The studio was known for creating violent driving games like Quarantine and Quarantine 2, as well as the sci-fi strategy title Dark Colony, and was in the process of working on an expansion to Dark Colony called Council Wars when it was acquired and renamed to Take-Two Interactive Software Canada.

For the next couple of years, the small team worked away on a bunch of ideas, including a potential open-world World War 2 game set in France, but none of these would ever see the light of day. Instead, Take-Two Interactive swept everything aside in 1998 and assigned the Canadian team to work on an expansion to the controversial crime game Grand Theft Auto, set in London. In order to pull this off, the developers would have access to DMA Design's original engine, as well as some other audio files and assets. It also got another new name: Rockstar Canada. Ray Larabie, a former artist at the studio, tells us more.

"We had just moved into a grungy spot under a fruit market near the Oakville waterfront and had been working on an open-world game with a WW2 theme," says Larabie. "We were kind of rambunctious and got evicted from our last office, so it was hard to find a suitable space. I think it was probably our experience working on Quarantine & other violent driving games that made us a perfect fit for the GTA London pack."

Blair Renaud, the map designer and sound director on Grand Theft Auto: London 1969, describes the atmosphere at the studio as often chaotic and out of control. He tells us that the studio was comprised of roughly 10-12 developers stuffed into less than "1000 square feet" and that the cramped office space and strong personalities led to some unhealthy clashes. Nevertheless, he clarifies that it managed to be a place of great creative freedom amidst these issues and the absence of HR.

"There were definitely some incidents that would be considered toxic by today's standards," Renaud recalls. "[A co-worker] and I got into an actual physical fight at one point. I'm not even sure what it was over. He just came over to my desk and started hitting me in the head with a rubber-severed hand I had on top of my monitor and shouting something. I stood up and pushed him to the wall, and we ended up rolling on the floor until we were pulled apart.

"[The director] Greg Bick was also notorious," he continues. "Some famous quotes from him were '9:30 dude!' if you were late (regardless of what time you left the previous night), and 'crunch time buddy'."

Rockstar Canada handled the vast majority of GTA London: 1969's development, but production was also split across three countries. There were the founders of Rockstar Games New York in the U.S, comprised of Sam Houser (executive producer), Dan Houser (producer/writer), Gary J. Foreman (producer), and Terry Donovan (musical research); the main development team at Rockstar Canada based in Ontario, Canada; and another team in London, England that included Lucien King (producer) and Somethin' Else's Paul Bennun (director of sound production).

A Virtual London

The project had originated in Rockstar's New York office as a way of keeping the attention on GTA, while the game's original developer DMA Design was busy developing its sequel Grand Theft Auto 2 in Dundee.

The idea for the game was to take what DMA had accomplished with the original GTA and apply it to a late-1960s London setting. You would be able to pick between one of four characters (eight in the PC version) loosely based on Charles Manson, Michael Caine, Sid Vicious, and a stereotypical mod, with the goal being to work your way up through the city's underground thieving and killing.

Instead of Hare Krishnas, the streets would be filled with football hooligans; buses would be red instead of bright yellow, and cars would drive on the left as opposed to the right. There were even special "dog eggs" on the pavement, which players could drive over to smear a brown skidmark across the sidewalk — a feature that Larabie proudly takes full credit for today.

"The ground tiles could be flagged as asphalt or dirt, which would affect traction and the skid marks when doing handbrake maneuvers," says Larabie. "Apparently in London in those days, dog poop on the sidewalk was a big thing, so I added special sidewalk tiles with little brown spots. When you handbrake across those pet dump sidewalk tiles, you'd get a big brown skid mark. I hope history will remember me for my crucial contribution to fecal vehicular skidding in games. I don’t think they were included in the PlayStation version."

Something worth noting is that, despite the game's central location, almost none of the staff at Rockstar Canada were actually British, except for Ed Zolnierczyk, who lived there briefly when he was a kid. As a result, the team couldn't rely on firsthand experience and instead needed to throw itself into research and reference-finding. Larabie, for instance, was a stickler for detail when it came to the cars, and went to great lengths to recreate some period-specific vehicles.

"I researched about 100 car models, and we narrowed it down," says Larabie. "I remember a bunch of us went to a mall and walked into a die-cast model car store and walked out with trash bags filled with cars. The shop owners must have been confused. That was the time when digital cameras were new, expensive, and horrible quality. We had a brand-new Sony Mavica, the kind with the floppy discs [that we used to take pictures]. The quality was terrible, but it was enough to get the job done."

The result was 60s-inspired cars like the Jug Swinger, Myni, and James Bomb. The Jug Swinger was an obvious nod to the Jaguar E-Type (or Shaguar) from Austin Powers International Man of Mystery, while the Myni and James Bomb paid tribute to The Italian Job (1969) and Goldfinger (1964) respectively. These cars weren't the only area that required this careful kind of attention to get right, however.

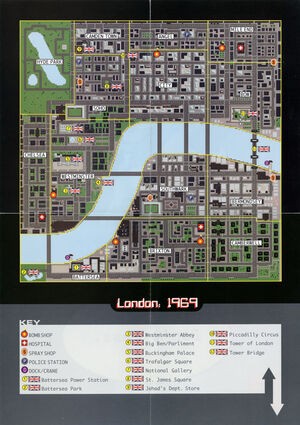

The expansion also included a completely new London map, which was comprised of fourteen different areas, including Hyde Park, Brixton, Soho, and Westminster. According to Renaud, who designed the map in the game, Greg Bick and Ray Larabie were responsible for the tile art for the city, and his job was then to take that work and assemble it into a coherent map. Sort of "like Minecraft".

"I remember watching a ton of car chase movies from the late 60s like The Italian Job, Bullitt, and Robbery to get the vibe we were going for," says Renaud. "Ronin had also just come out and I remember being hyped for that. As for the map itself, I basically cleared the reference material from the local bookshop (the internet still wasn’t great in 1998). Everything from tourist guides and visual dictionaries to just plain old road maps. Basically, anything that had any pictures or information about London was fair game."

"I tried to include everything I could," he adds. "Of course, all of the major landmarks had to make an appearance, Westminster, Tower Bridge, Piccadilly Circus, the Palace, etc. but, I also tried to give every borough its own distinct flavour. It’s tradition for the GTA series to be as accurate as possible with the maps. It was a lot of fun. I’ve still not been to London, but I feel like I know my way around pretty well now. At least a late 60s version of it."

The Gangs of London

With the city taking shape, the game needed a story, and in the case of GTA London: 1969 that responsibility fell to Dan Houser — someone who would go on to become a key creative figure behind later games. At this point, Houser had only worked on a few games, including as a producer on the European version of You Don't Know Jack: Volume 2. Nevertheless, he stepped up to pen much of the dialogue and came up with a wraparound plot about a small-time crook returning to London from Liberty City and getting involved with the local mob.

Players would start off stealing a scooter off the street, before carrying out a bunch of busy work for fictional London crime bosses like Harold Cartwright, The Crisp Twins, and Jack Parkinson. Much like in the original Grand Theft Auto, players would visit the pay phones spread across the city to receive missions, with additional jobs being offered through the in-game pager. The story was mostly communicated via text on the screen, but there were also cutscenes featuring animated characters, all of which were voiced.

Paul Bennun was the director of sound production at the London Studio Somethin' Else contracted to record the dialogue in the game: everything from the pedestrian barks to the dialogue of the London mob bosses. He was also in charge of managing the large amount of high-quality audio assets being collected. He gave us an insight into the narrative development of the game.

"I seem to recall that Dan Houser fancied himself a writer [...] and was gifted some of the narrative [and] dialogue on that title," says Bennun. "Lucien and Sam [also] had a bunch of strong ideas about what should happen. We wanted it to be irreverent, more cartoonish, we wanted it to be very funny, and that’s how we approached the design of both the radio stations and also the environmental character audio and so on."

Irreverent and cartoonish is a perfect way of describing the tone for the expansion. The characters speak with exaggerated cockney accents, messages flash up on the screen telling you that you're "Brown Bread" or "Nicked", and NPCs are constantly shouting "Bastard" and other obscenities in your face. The Rockstar execs were constantly pushing for this more anarchic, comedic tone, and Rockstar Canada followed its example.

"Dan was steering the ship in terms of style, so we followed his lead," Larabie recalls. "I remember Dan's initial explanation was that it was a parody of British crime wave stories. The impression I got from him was that it was going to be full of jokes, cockney slang, caricatures of the Krays, etc. Greg Bick always tried to inject comedy in his game designs, so there would have been zero resistance there anyway."

Though it's probably hard to imagine now, given the success the series has gone on to experience, the budget for Grand Theft Auto: London 1969 wasn't particularly great. As a result, many of the voices that brought the story to life belonged to members of staff and whoever happened to be in the studio at the time. A testament to this is the casting of high-brow figures like theatre director Simon McBurney and the respected art critic John Berger, who were simply recording in the same Brick Lane studio.

As Bennun explains, "John Berger wrote a book called Ways of Seeing. He was in his seventies and he is one of the most important figures in Art Criticism and Art History of the 20th century. Like if you look up John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, you’ll see what I mean. He's a fucking legend. Simon McBurney, he’s in His Dark Materials. He led a theatre company called Théâtre de Complicité. He’s just directed a series for Radio 4. He’s also another high-end, sort of figure in arts.

"These guys just happened to be in the studio when we were recording and I needed a voice of a mob boss, so I asked John Berger if he’d do it. And as a result, you’ve got John Berger, which is the unlikeliest bit of casting of all time, and then Simon McBurney who plays [another character] on it. The ad-hoc improvised nature of the way we approached a whole bunch of the audio on this project is just something that would be impossible for modern-day development. It just could not, would not happen."

From playing GTA: London 1969 today, it's clear the story isn't as substantial as the narratives of the games that followed, but it includes enough fun references and allusions to classic films like The Long Good Friday, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, and The Italian Job to keep you invested in its warped recreation of London. Instead, what really made the game shine was the game's audio, particularly its soundtrack.

The Sound Of The Sixties

While Grand Theft Auto featured mostly original music on its radio stations, Grand Theft Auto: London 1969 included a much more significant focus on licensed material and this went a long way to immerse players in the era.

Rockstar New York's Patrick Whittaker and Terry Donovan were responsible for sourcing the music that appeared on these radio stations, cutting deals for the rights to music from Trojan Records, Beat Records, and Neopolis Records. Bennun, under the supervision of King, was then given the task of editing all of these tracks together inside a radio format, recording DJ voices, and sending the files over to North America. The result was a soundtrack that paid tribute to 60s' Ska music and Italian crime cinema.

Bennun recalls, "There were a few things that [Rockstar Games] knew that they wanted to do and they had some relationships with some rights holders. So we discussed it and sometimes they would come and say we have the rights for this, we have the rights for that, we want to do this, we want to do that. And we would take those rights and take that material for the radio stations and other times it was just stuff we created ourselves."

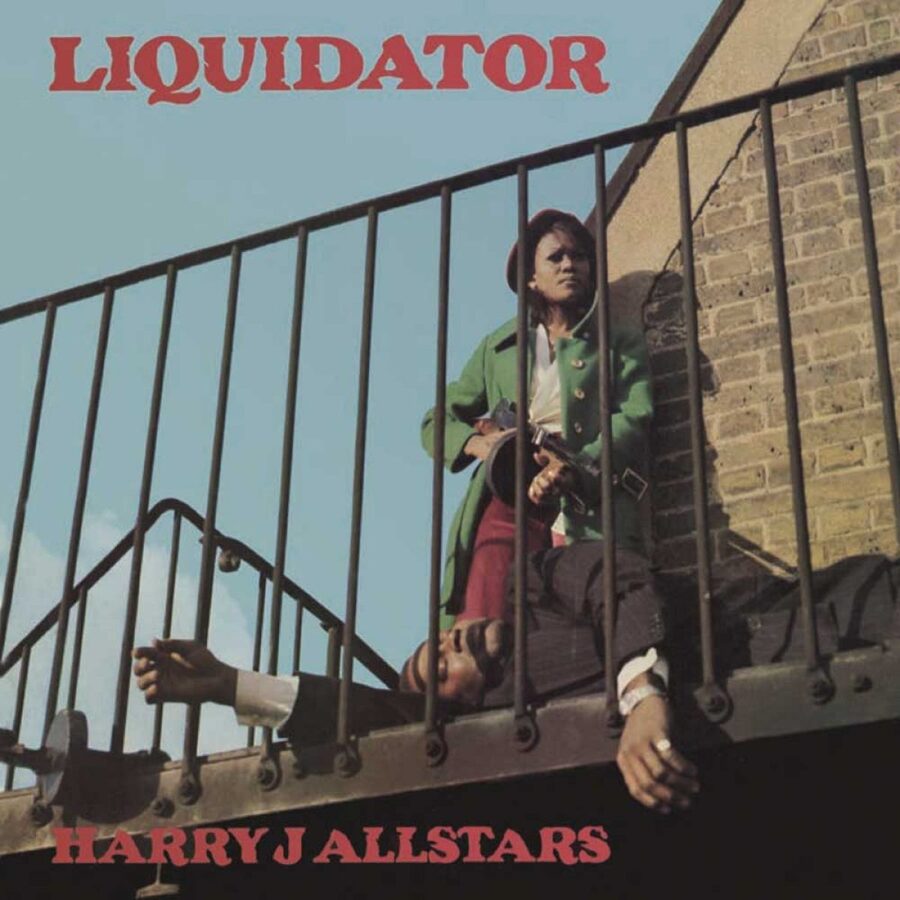

Driving around London, players could tune into tunes from Harry J. All Stars and The Upsetters on stations like Bush Sounds or Heavy Heavy Monster Sound, or opt instead to listen to Italian pop songs like 'L'Uomo Che Saprà' and 'Beat Fuga Shake' on Blowup Radio or Kaleidoscope. There were 12 stations in total, with only four of these actually original music written specifically for the soundtrack:

- Bush Sounds: Plays Reggae Music

- Heavy Heavy Monster Sound: Plays Reggae and Ska

- Blow Upradio: Plays Beat music

- Kaleidoscope: Plays Pop and Beat music

- Sound of Soho: Plays Jazz

- Radio Penelope: Plays Pop and Soul

- Radio Andorra: Plays Pop and Beat

- Westminster Wireless: Plays Soul and Jazz

- Radio 7: Plays Beat and Funk

- GTA Pomp: Plays Classical

- GTA Spy Theme: Plays Jazz

- Austin Allegro Chase: Plays Funk

Working parallel to Bennun across the pond in Canada was Blair Renaud. While Bennun handled the VO and radio stations, Renaud was the person in charge of the sound design for the vehicles, guns, menus, and pickups. He had inherited some audio files from DMA Design but as he tells us, he also sourced additional sounds by sampling from old VHS tapes. This included films like Bullitt and The French Connection.

Renaud tells Time Extension, "Like everything else, I wanted to nail the vibe or late 60's London. As far as what that means for cars and guns, I guess it was more about matching the engine sounds from that era. The fun stuff were the power-ups and menu sounds that were more like jazzy trumpet stabs and the like. We had access to the full library of audio from the original GTA, but all of the new stuff was sourced by me. A lot of it was ripped (sampled?) from VHS tapes, and some of it was from some CD sound libraries I had."

All of this effort led to a coherent audio design that reinforced the period setting and location. Selecting from the main menu delivers the iconic bong of Big Ben while collecting weapons and tips would play a musical sting befitting the period. It was the cherry on top of an already slick expansion. All that was left was to release it to the public. And in April 1999, Rockstar Games did just that, publishing Grand Theft Auto London: 1969 simultaneously across both PC and PlayStation.

What Happened Next?

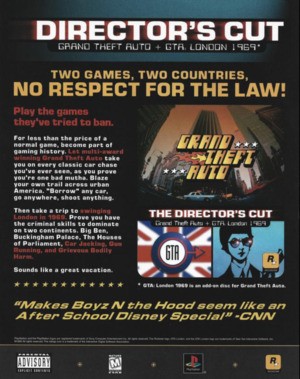

Compared to the original game, GTA London seems to have received significantly less blowback from the general press, with some newspapers like the Hinckley Times even acknowledging that the simplistic graphics did much to hide the more gratuitous moments. That didn't stop Rockstar from advertising it at the time with some fairly inflammatory interviews and advertisements, however, in order to drum up controversy and sales.

In one interview with Extreme PlayStation, for instance, a Rockstar representative stated the reason the publisher pursued the add-on was "the opportunity to make a game which calls the player 'a right awkward ponce' was too good to miss". The game's website, meanwhile, doubled down on this, prominently displaying the character Randy Morash with the quote "Don't mess sunshine. Or I'll kick your bloody head in. Understood ponce?' It all feels a little desperate to offend and has aged like milk in the intervening years.

As for the gaming press, the reaction was largely mixed. PlayStation Pro was one of the more enthusiastic publications. It awarded the game a fantastic 91% and concluded, "GTA London is every bit as dangerous and deliriously funny as its older brother therefore that means it has to be worth owning." Gamespot, on the other hand, gave it a middling 5.9 out of 10 and argued: "Grand Theft Auto just has too many problems to make it anything more than a premise in search of a better game. All you would-be thugs out there keep your fingers crossed and hope the sequel addresses these problems."

Despite the reviews being all over the shop, one thing almost every reviewer could agree on was that the sound and the music were two of the game's best features. In fact, later that year, it was even nominated for an award at the 1999 BAFTA Interactive Entertainment Awards for 'Best Sound'. Though, as we found out, this itself became a point of controversy.

According to both Bennun and Renaud, Rockstar put the game up for award consideration without informing the artists that had actually worked on the sound. When it eventually won, Bennun, who was in attendance at the ceremony, then had to sit in the crowd and watch as a Take-Two representative got up on stage and claimed the award for work that he and others did.

Bennun recalls, "We went on the night and I see this marketing dude going up and giving this shitty speech about how amazing they’d been and what great work they’d done on this title, like one, I don’t know who the fuck you are. Two, I’ve never heard of you. Three, have I mentioned I’ve never heard of you? Four, you have nothing to do with the thing that you’re claiming credit for. Nothing at all."

Enraged at this turn of events, Bennun sent an email to BAFTA who immediately tried to remedy the situation. In response, BAFTA contacted Rockstar, who reluctantly agreed to pay the fee to produce another statue. The Academy also altered the rules for craft awards moving forward so that the team responsible had to accept, rather than the publisher.

In Canada, Renaud was completely oblivious to what had occurred and wasn't even aware that his work had won an award until Rockstar Canada studio head Kevin Hoare told him about it after the fact.

"At the time, I don't think I even knew what a BAFTA was," he tells Time Extension. "It's nice to hear that someone else was upset about it though. It's pretty disheartening to know that you should have an award and someone else took it. I remember asking about specifics later and being told (again probably by Kevin) that it was awarded to Rockstar, not me, so it's probably sitting in the head office."

After leaving Rockstar Canada in 2003, Renaud has tried on several occasions to contact BAFTA to get another statue made and shipped out to him. Sadly, he has yet to make any headway.

Grand Theft Auto: London 1969 didn't set the world on fire, but it did a good job of tiding people over until Grand Theft Auto 2 appeared later that year and also influenced later titles with the way it embraced licensed music. In July 1999, a freeware prequel called GTA: London 1961 was released for PC, which featured additional missions, one new cutscene, and a multiplayer "deathmatch" map based on Manchester, England. It would mark the last game to take place outside of America, with the series returning to the states in GTA 2 and sticking with it ever since.

Rockstar Canada, meanwhile, continued operating under the Rockstar banner. It worked on console ports for games like Max Payne and Oni during the early 2000s before changing its name to Rockstar Toronto in 2002, to avoid confusion with Barking Dog Studios (which had recently been renamed to Rockstar Vancouver). Since then, Rockstar Toronto has released The Warriors, a licensed tie-in to Walter Hill's 1979 film of the same name, and continued to support Rockstar's other projects. Demands for a new London-based GTA seem to grow every year, but it looks unlikely the series will ever make another visit to the UK capital.