When Populous was first released in 1989 for the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST, it became an almost overnight success for its creators: the Guildford-based company Bullfrog Productions.

Generally considered to be the very first "god game", the groundbreaking strategy game transported players to an isometric world where they were the masters of their own civilization, with the main objectives being to grow their number of followers through manipulation to defeat the worshippers of a rival deity. Publications like Computer & Video Games described Populous as "one of the most enjoyable and rewarding games to appear on a computer", while others like Computer Gaming World awarded it their "Strategy Game of the Year". Anticipation was therefore high to learn what the studio was working on next, with Bullfrog eventually teasing a 3D follow-up to Populous in magazines, to be released the following year.

Powermonger, as this game was eventually called, was published in October 1990, and, on its surface, had a very similar concept to Populous, pitting you and an army of followers against a computer or a friend across several maps. But instead of controlling a deity, this time around it cast players in the role of a mad warlord, with the overall goal being to tip the balance of power (represented by a bunch of scales) in their favour.

Similar to Populous, Powermonger eventually went on to earn a bunch of glowing reviews from the press as well as a string of industry awards. However, unlike Populous, its star has gradually faded over time, with the title typically being overlooked today when people talk about the company's successes. Because of this, we've always been interested in taking a deeper look at the making of this fascinating yet flawed title to explore what Powermonger got right and discuss some of its shortcomings that have become more evident over time. So recently we reached out to several members of its original development team, including Glenn Corpes, Gary Carr, Alex Trowers, and Jonty Barnes.

Creating A Virtual World

The story of Powermonger begins back in January 1989 inside a cramped set of offices above a hi-fi store on Guildford's Bridge Street. Despite Populous's success, Bullfrog had yet to upgrade to a more spacious office space, with employees still having to fight for any available room they could find to eke out a place to work. It was within this slightly chaotic environment that Glenn Corpes, the creator of Populous's engine, sat down one day and began to program a new three-dimensional engine for the Atari ST.

As was common with a lot of Bullfrog games, there was no detailed plan in place, just the vague idea that the company should try to expand on the technology they had created for Populous and a suggestion from Peter Molyneux, Bullfrog's charismatic studio head and Populous's co-creator, that it might be interesting to take things in a slightly different direction.

"Peter had said that he wanted to do a game that was more like a war game," Corpes tells Time Extension. "Peter wasn't working on it. I mean, I was working on it in isolation at first, so I had the whole view, the look of it, and the sort of little people in groups, ranking into armies and stuff. But I didn't really know exactly what I was aiming for. It was basically an attempt to do a Populous engine in 3D polygons. And that's what it started out as. It was all done just speculatively. So there was no strategy, no game. It was just the engine and a testbed for navigation."

We wanted to have another game where you view the world by looking down on it, as we feel that format still has plenty of potential. But the problem with the Populous view, and indeed the way in which Populous is written as a whole, is that it's very restricted in terms of its mechanics.

Working on his own, the programmer decided to put together a short demonstration of the new engine and present it to other people inside the company. This ended up impressing everyone who saw it — not least Molyneux, who suggested that this technology should form the basis of the company's next product.

Speaking to The One Magazine in 1990, Molyneux said about the project, "What we wanted to do after Populous is...well, we knew that we could get more — and better — games out of this sort of world view idea that we had developed. That's not to say that we wanted to do a Populous rip-off, but we wanted to have another game where you view the world by looking down on it, as we feel that format still has plenty of potential. But the problem with the Populous view, and indeed the way in which Populous is written as a whole, is that it's very restricted in terms of its mechanics - it's only made of blocks after all so you can't produce any very varied shapes."

Molyneux's idea for Warmonger, as this project was known at the time, was for it to be an evolution of Populous. Again, players would be battling against a rival army for land. However, this time around, they would have access to a significantly expanded set of options.

Not only were there now plans for new unit types with their own individual routines, like "farmers, fishermen, and shepherds, merchants, cattle ranchers, thieves, and so on", but players would also be given a greater level of control over their followers too, being able to order them to take over settlements, trade with villages, gather food, invent, and even spy on their neighbors to reveal their enemy's positions. The only downside was that players would now no longer be able to directly terraform the environment to alter the landscape, thanks to the change in engine, but Bullfrog assured players that they would still be able to impact their surroundings in more subtle ways, through the kinds of orders that they were delivering to their armies.

In 1989, for example, Molyneux told a BBC film crew about the project, “We are desperately working on the routines that will allow you to [...] visit a world. You will only be a member in that world, be able to walk around it, and be able to maybe influence the world in a very minor way. An example would be if you were to walk up to a tree within the world to chop it down. To go away and come back a year later, you’d find a new tree growing in its place but the stump still remaining there."

This was an example of the type of exaggerated promises that would eventually end up landing Molyneux in trouble decades later. However, it's a perfect reflection of where his head was at, at the time. Despite previously suggesting to Corpes that they could try to make a war game (and the project itself having "War" in the title), Molyneux was becoming much more preoccupied with the idea of creating believable 3D worlds, with the fighting being something of an afterthought. In fact, in interviews, he would often steer clear of referring to the title as a war game directly, instead opting to describe the project as a "strategy-oriented" "simulation of a kingdom".

He believed that if he could make the world more realistic, it would present more possibilities to the player and expand replayability, ultimately making the game more fun for the player to inhabit. They would just need to build enough detail into the simulation to keep the players entertained with every playthrough.

A New Perspective

With a loose set of design pillars in place, the decision was made to assign a couple of artists to the project, namely Simon Hunter and Gary Carr. Hunter was just a teenager at the time and was new to the industry, while Carr, on the other hand, was slightly older and more experienced, having previously worked at Palace Software — the developer of the Barbarian series.

Together, their job was not only to create a bunch of characters and objects (such as trees, buildings, people, and animals) that would populate the world, giving Corpes's 3D environments the illusion of a living, breathing world but to establish a visual identity for the game — one that would further help distinguish it from its predecessor. This was especially important, as, up to this point, neither Corpes nor Molyneux had written a proper story outline for the game, or given much thought to what the theming to their world would eventually be.

Both artists put together potential treatments for what this identity could potentially look like, with Hunter pitching a futuristic Tron-like layout for the game's UI featuring floating heads and lasers, while Carr instead worked away on a sword and sandals-esque variation of the concept, inspired by the 1963 fantasy adventure film Jason and the Argonauts.

Carr recalls, "At some point, I seem to remember us talking about the gods in Jason and the Argonauts. So there were these few scenes where it would go back to the gods who had been checking in on Jason and the Argonauts and they would look into this pool which was kind of a magnifying glass pointed down at planet Earth and it just felt like a really good, theatre for the game. You could have your generals looking down in this sort of abstraction, and that seemed really interesting to us and also allowed us to make a full-screen-looking game but with 3D elements which were probably only a quarter of the screen space."

Presented with the two proposals for the game's world, Bullfrog ultimately went with Carr's, with the studio later commissioning a demo scene group named E.S.D to put together a short intro for the title in the same style. This wouldn't be the only bit of outsourcing the company would end up doing for the project either, with Bullfrog also contracting a French sound designer named Charles Callet to create a compelling soundscape for the game's world, based on being impressed with his previous work on the PC title Drakkhen.

As for the responsibility of generating the 3D maps, that responsibility fell to Alex Trowers, a young hire at Bullfrog, who had previously got his foot in the door by helping the company test games on weekends. Upon booting up a copy of Powermonger, players would be presented with one large two-dimensional map, which was divided into various continents that represented different playable levels. Trowers' job was, therefore, to generate these islands using Corpes' landscape generator, and then individually place each item using a custom editor. As he recalls, it wasn't exactly the easiest of processes.

"It was horrible," says Trowers. "It was and remains the worst editor I've ever used. The editor fit at the top of the screen where the little row of icons was, showing what each captain was doing. It was like five pixels tall or ten pixels tall in this little strip at the top of the screen and all I would edit would be the random number seed that determined the landscape generations. And then I could step through a number of things that I could place down.

"Everything was just like a series of numbers up at the top of the screen, a series of four-digit numbers. And the way that Glenn had implemented it was above each digit of each number was an up or down arrow, so I'd have to click so many times on the things to get to a particular number on these tiny little three-by-three icons to submit that thing and then generate it and see what it did in the world. It was a painstaking process to actually use it."

Reviews, Rumours, & Sheep

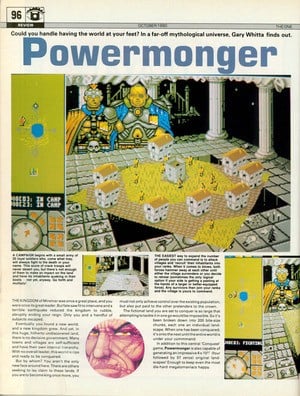

Despite the slightly disorganized and improvisational nature of Powermonger's development, it would eventually end up being released for Atari ST and Amiga in the latter part of 1990 and would go on to earn a bunch of strong reviews from the outlets of the time.

The One Magazine, for instance, wrote that it was "a joy to learn, and well nigh impossible to leave alone", while CU Amiga argued that it was "destined to become a classic". The following year, it even went on to sweep several awards at Generation 4 magazine's annual Golden 4 awards, including Best Strategy Game and Most Innovative Product, signalling the company had another hit on its hands.

Speaking to Time Extension about the response, Trowers recalls, "That's sort of like the period of Bullfrog. From Powermonger to Populous II, Syndicate, Theme Park, and Magic Carpet — all the way through that, we were just at the absolute pinnacle. We were just sweeping up at these awards.

"I think Powermonger is also responsible for the highest rating that we've ever got for a game because Ace Magazine gave it [973] out of a thousand and that was the highest we'd ever got. Do I think it deserved that? No. But I think people were kind of wowed because it looked so different. Technically, it was right up there. We didn't know an Amiga could do this."

As players got their hands on the game for the first time, individuals could finally put Molyneux's new kingdom simulation through its paces, leading to various stories and rumours emerging about what players discovered. One of the most surprising of these was related to the behaviour of the shepherds in the game, and the belief that it was occasionally possible to catch them performing unspeakable acts to members of their flock.

"It was supposed to be that you could see someone shagging a sheep," Corpes tells us. "So, basically, there were shepherds who had sheep with them. And if you recruited a shepherd into your army, his sheep would follow him. So it doesn't follow you, it follows him. I think that probably got printed in the magazine at some point, because of something Peter had said. It might have even been an April Fools."

According to the team, this wasn't something that was actually hardcoded into the game but was instead a bug that emerged from the character's pathfinding. Every so often, a shepherd would wander off track, which would cause them to wiggle side to side to find their bearings. However, because of the simple two-frame animation and the fact that there were sheep nearby, it would occasionally appear slightly more suggestive than it was, causing players in the early '90s to speculate that Bullfrog had secretly hidden a lewd Easter Egg for players to find.

This type of misunderstanding was something that Molyneux was often known to encourage when speaking to the press, with Trowers remembering a similar example of "an introduced fallacy" related to the game Theme Park.

"When we started showing Theme Park to journalists, the mechanic in that game would fix a ride and wander off," Trowers recalls. "And all they would do is they'd pick a random spot and they would walk there and they'd do their idle and then they'd pick another random spot, and another, and another until they were called to do another ride.

"On one occasion, the mechanic had fixed the ride, and the random spot he'd chosen was behind the entrance. So a journalist had asked Peter what he was doing and Peter quick as a flash had gone, 'He's nip behind there to have a fag and he knows that you can't see him.' But he hadn't. He'd just chosen that spot completely at random and there were no smoking animations in the game. But suddenly it became this thing where the AI was so clever that it would go and they'd sneak away from you."

Stories like this — however ridiculous and bizarre — were a validation of the kinds of design principles that had driven Powermonger's early development, with the sandbox occasionally delivering humorous and unexpected moments that would keep the player coming back. It didn't matter if these moments were sometimes the result of the player's imagination or a misinterpretation, as long as the player believed that the world was still capable of offering up new surprises.

The Legacy Of Powermonger

With all that being said, however, it's impossible to ignore some of the game's rough edges if you were to revisit it today, with the most obvious issues being its confusing icon-based UI, which requires a manual to learn how to play (a holdover from Populous), the slow frame-rate (which can be sped up by zooming closer into the map), and the lack of an automatic win-screen. Once the player had beaten a level (as indicated by a set of scales on the left-hand side of the screen), they would have to manually retire, at which point they would be allowed to select another map and continue their campaign. This is something, again, which is clear to those who have read the manual but doesn't exactly make for the smoothest experience.

Speaking about the project now, most of its former developers argue that many of these shortcomings could have potentially been ironed out with a bit more time, but stated the company was under a lot of pressure to get the title out the door, due to its agreement with the game's publisher Electronic Arts, and that Molyneux himself was often too busy elsewhere with other projects, to give the project the attention it deserved.

Jonty Barnes, one of the testers on the game, remembers, "Peter had loads of stronger ideas for Power Monger. And it was pretty clear there was some financial pressure on why it got released. If you look at the release date, it's just before Thanksgiving, which is obviously an important time for U.S. and European sales, especially back in the days of box products. So I'm pretty convinced that, you know, Peter didn't get to finish all of the designs that he had intended for the game. When you talk about the fact that there's no automated level completion when the scales are in your favour, I bet that's a symptom of that"

Corpes, meanwhile, adds, "It must have been a very stressful time for Peter because he did the whole PC port of Populous almost on his own. Then when that was done, he sort of locked himself in a room and, you know, his sister was worried about him at the time. She thought it was driving him mad. And I mean, Populous was made with the sort of relaxed atmosphere of people playing multiplayer against each other every day, whereas Powermonger was more of a sort of, "Shit, we promised EA we'd get this done by this time" As a game, I don't think very few people were as bought into it as they had been on Populous. I definitely wasn't."

In an interview with People Makes Games in 2019, Peter Molyneux reflected briefly on the making of Powermonger but didn't choose to mention the pressures of the project as being responsible for its shortcomings.

Instead, he attributed many of its failures to his own limitations as a designer, telling People Make Games, "This could have been the first true RTS game. Except for one slight problem. And that was me being rubbish as a designer. When you’re designing a game you let reality get in the way of gameplay. So what I thought with Powermonger was we can control these units and send them places, but how are these orders getting to these people? And that's when I got obsessed with, well, we can have a little runner run across the land or, I know, it will be a carrier pigeon. And that was such a stupid decision because it meant that the point-and-click side wasn't immediate. If you compare that with Starcraft, it's all about the immediacy of that point-and-click"

Similar to Populous, Bullfrog ended up releasing various ports of Powermonger on other platforms following its initial release on Atari ST & Commodore Amiga, including MS-DOS, PC-98, X68000, Sega Mega Drive / Genesis, FM Towns, SNES, Macintosh, and Sega CD. There was also talk of themed expansion packs for the game, introducing new levels and generals, with the studio releasing a WW1 edition of the game in 1991.

Today, Molyneux credits Powermonger as being the game that taught Bullfrog a valuable lesson about game design and what not to do, while Trowers and other members of the team note that the game's AI went on to inspire an earlier version of Syndicate, as well as led in a roundabout way to the tools developed for Magic Carpet — the company's first fully 3D title. Echoes of Powermonger can, therefore, be felt throughout Bullfrog's library, even if its reputation has declined in the decades since.

Hopefully, one day, the game can be released on modern digital storefronts like GOG & Steam, allowing players a chance to experience the ambitious yet flawed title in all its glory.