Few companies have produced as many "arcade hits" as the video game giant Konami. The Japanese developer and publisher — founded all the way back in 1969 as a jukebox repair business — is behind some of the most beloved arcade titles: from puzzle-action games like Frogger to a huge collection of classic shoot 'em-ups and side-scrolling beat 'em ups.

Yet, in spite of this success, there is a shockingly small amount of information available about the people who actually made these games, in part due to Konami's decision not to credit its developers in order to avoid other companies headhunting its talent. So, recently we set out to interview three former Konami employees — the programmer and producer Masahiro Inoue, illustrator and designer Yoshiki Okamoto, and designer and artist Masaaki Kukino — to find out more about their careers and what it was like working on some of the company's biggest games. The interviews were conducted primarily in Japanese and were translated with the assistance of the Japanese-to-English translator Liz Bushouse.

During our discussion, we talked about everything from Konami's early arcade games like Frogger and Circus Charlie to later cult classics like Crime Fighters and Asterix. Without further ado, let's dive in!

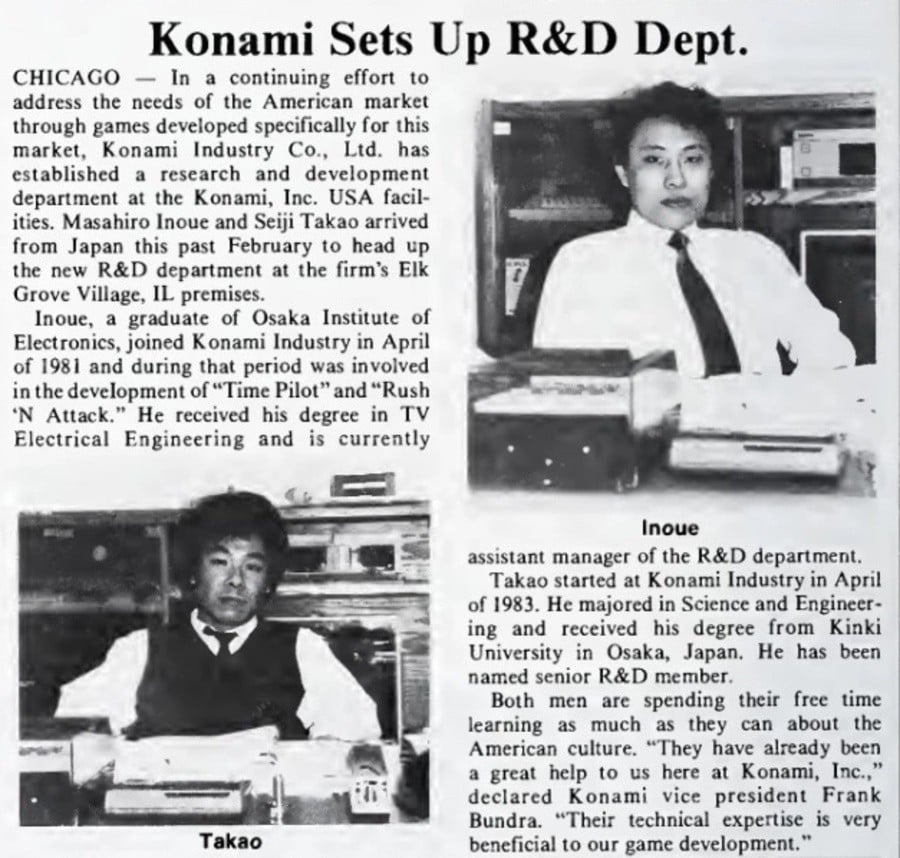

Masahiro Inoue - Programmer/Producer

Masahiro Inoue worked at Konami from 1981 until 2008. During that time he helped develop games like Frogger, Time Pilot, and Gyruss, rising through the ranks from a sound programmer to a producer, before eventually becoming a member of Konami's management team. Today he is a teacher at a middle school in Osaka, Japan, and was more than happy to answer some of our questions about his long and amazing career in the games industry.

Time Extension: Let's go back to the very beginning. How did you get the job at Konami? What was the company like at the time?

Masahiro Inoue: I went to a specialized school to be a TV repairman. I studied hard there and enjoyed that. But then I realized that the times had moved on and maybe TV repairmen weren't as in demand. Like, that job isn't going to exist anymore. So I said farewell to that and started looking for other things to do. That's when I found a company called Konami that created electronics but also had a development division. And that they'd pay 200,000 yen salary for people who'd just graduated, which was a lot of money at the time. So I went for it, did the interview, and then came back. That's when I got a call saying I was in.

There was no test, only an interview, so I was shocked. They mostly wanted to increase their staff after the shooter Scramble was such a huge hit, and seemed to have a bright future ahead of them.

Time Extension: Konami had a policy of not crediting its developers, so it's often hard to tell who actually worked on what. Could you tell us a little about the projects you were personally involved with at the company?

Masahiro Inoue: So, the first games that I did for Konami were Turpin and Frogger. I did the sound of the turtle character from Turpin and the sound of the frog from Frogger falling into the river. They were both created with the Programmable Sound Generator (AY-3-8910) for Z80. I was also directly involved in programming all of the following too (there are far too many titles on which I was Director/Producer, so I'll leave those out for now):

- Jungler (1981)

- Locomotion (Gattang Gottong) (1982)

- Pooyan (1982)

- Time Pilot (1982)

- Gyruss (1983)

- Circus Charlie (1984)

- Time Pilot ‘84 (1984)

- コナミのピンポン (Konami's Ping Pong) (1985)

- バブルシステムの書き込み/読み込み (Reading/Writing for the Bubble System) (1985)

- Double Dribble (1986)

- Hyper Crash (1987)

- Blades of Steel (1987)

- リングの王者(The Main Event) (1988)

- Crime Fighters (1989)

- Surprise Attack (1990)

Time Extension: Frogger obviously went on to become a huge hit for Konami. Did anyone working on the game expect that it would become such a big success?

Masahiro Inoue: I had just joined the company, so I didn't know if it would sell or not, but I was surprised that Sega bought the distribution rights. Later it became a handheld toy, and all the employees (dozens of us?) got one.

Time Extension: Besides Frogger, another one of the arcade games that you worked on while at Konami was Time Pilot. What was the original idea behind that game?

Masahiro Inoue: The programmer Takahide Harima had previously made the pool game Video Hustler in 1981. That game traced a white ball's path as it bounced around and gave us the idea of trying to depict countless bullets being shot from the center of the screen. I was the programmer in charge of sound, so I don't know all the details, but I can tell you the secret behind Time Pilot's graphics.

The bullets that the aircraft was spraying in 360 degrees, or perhaps 64 directions, were not OBJs, but VRAM. This is what allowed a huge number of bullets to move around on the screen. If the player's ship changed direction, the relative movement of the bullets would be affected. However, the player isn't really able to notice this.

As for the time travel element, either Harima-san, the team leader, main programmer, and hardware designer, or Yoshinori Okamoto, the designer and planner, came up with that aspect of the game.

Time Extension: In between Time Pilot and its sequel, Time Pilot '84, you worked on both Gyruss and Circus Charlie. Do you have any interesting memories of working on either of those games?

Masahiro Inoue: The Circus Charlie team would often hold planning meetings, but inevitably the graphics programmers’ opinion would take precedence, or the idea would be rejected if the graphics programmer said an idea was impossible. So, I studied graphics programming on my own after working on Gyruss, where I had been a sound programmer.

When there was an opening for a graphics programmer, I immediately raised my hand. That was how I became involved with Circus Charlie. I was suddenly entrusted with three of the stages: the flying trapeze, horseback riding, and lion riding. I was also entrusted with the planning of these events, so I enjoyed myself as much as I wanted to.

In the trapeze, I was delighted with the performance that made the OBJs look three-dimensional by connecting them with a bunch of beads, but the controls were perhaps a little too unique, which I now regret.

Time Extension: You later worked on the sequel to Time Pilot, Time Pilot '84. You previously told us that was possibly the hardest project you worked on at Konami. Why is that?

Masahiro Inoue: Mr. [Toshio] Arima was the leader/main programmer on it, but partway through he left to go work at Capcom, so I took over for him. At that point, though, the game was already way over capacity/memory, the processing times were horrendous, and planning was only in its early stages. It was a real handful. Eventually, I had to discard the program created by Arima-san and start all over.

Time Extension: You told us that in 1986 you moved to Illinois in the US for two years to head up an R&D department where you did some research into the differences between the Japanese and American video game markets. Could you tell us a little more about that?

Masahiro Inoue: Yeah, sure. So, we created a document for the reference of game developers for home consoles and younger developers creating arcade games, to give them tips on how to create games for the American market. It was aimed at Japanese developers who were unfamiliar with American culture.

At the time, I had no idea if this would bear fruit, but after ten years of clear success, I think I can say it was the right choice. Some parts aren't suitable for the Japanese market, but other parts are still useful. Similarly, some parts aren't suitable for things outside of game development, while other parts are still quite useful. It wasn't any sort of official company policy, but rather some advice from me - after returning from 2 years and 5 months spent in America - for creating more games targeted at America from within Japan. All responsibility for the creation of it was mine alone.

Time Extension: When you came back, one of the larger games you worked on was Crime Fighters, which is obviously inspired by American movies. Do you know who was responsible for that game's comedic elements?

Masahiro Inoue: I think that was me! I like it. Like the licking posters and the dog huffing and puffing. The character sprites were drawn by the character designers, but the display time of each animation was adjusted by the programmer. I was in charge of programming all the enemy characters in Crime Fighters, so I created the animations for all the enemy characters. The animation of the main character, meanwhile, was created by C. Lee.

Time Extension: You previously told us that you were among those encouraging the Konami arcade division to pursue more licensed games, which inevitably led to games like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1989) and The Simpsons (1991). Had they already made any licensed games at that point?

Masahiro Inoue: Yes, so strictly speaking, the first licensed game for the Famicom was Track & Field. For animated show licenses, that would probably be Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, I think. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was already a hit as a comic, as was The Simpsons as a TV show, so we already knew they'd sell if we turned them into video games. And obviously, we were right.

Time Extension: As a final question, it would be interesting to hear, when did you leave Konami? And why? What did you do after leaving the company?

Masahiro Inoue: I left the company in May 2008. At that point, I could no longer really do the things I wanted to do, and all I was doing was creating entries in established series. Also, to be honest, I always wanted to get into education. I'd developed the desire to create educational materials ever since I went to America. So since it seemed like I'd already lost my place at the company, I figured there was no harm in seeing if they'd let me do something like that. And of course, the answer was no. So I told them I was done and I left the company. I went on to found an educational company called Learningvote Co., Ltd (currently shut down). I also now work at a middle school.

Yoshiki Okamoto - Illustrator/Designer

Yoshiki Okamoto joined Konami in 1982 fresh out of technical school. While at the company, he would be responsible for the design of two classic Konami games (Gyruss and Time Pilot), as well as contributing to a third title (Time Pilot '84) shortly before being recommended by a senior employee to quit the company rather than be fired directly (a surprisingly common practice in Japan) in 1984. Later on, he joined Capcom, along with fellow Konami alumni including Tokuro Fujiwara and Toshio Arima, where he worked on games like 1942, Gun.Smoke, Final Fight, and Street Fighter II. He is currently an investor/strategic partner for the metaverse gaming platform Creta and makes development videos about his lengthy career on YouTube.

Time Extension: How did you first come to arrive at Konami? What was Konami like when you joined?

Yoshiki Okamoto: Before joining Konami, I studied design at a technical school in Osaka for two years, majoring in graphic design. I joined Konami as an illustrator. I remember there being about 80 employees there at the time. I think the year before I joined was the first year they started hiring people fresh out of college.

The Konami office was located in its own building quite a ways away from Shōnai Station (which was in a bad part of town). I think the entire development team worked there. It was a small, triangular building, with three stories above ground and one basement level. The main office was in a new building that they rented out right by the station in the Umeda district of Osaka.

Time Extension: What was the first project you worked on at Konami?

Yoshiki Okamoto: My first project after joining Konami was developing Time Pilot. I was in charge of graphic design and planning.

Time Extension: Could you tell us more about the story behind Time Pilot’s development? For instance, who thought of the time travel element?

Yoshiki Okamoto: Time Pilot came about when my boss told me to make a "driver training school" game. I completely ignored my boss's instructions and completed Time Pilot instead. I was told that the development time would be 4 months and that I should complete it in 3 months, but that was impossible. So I worked overtime, staying up late into the night and working on days off to get it done. I'd work until 5:30am every day. But I never once hated it because I was surrounded by fun colleagues and kind superiors, and most importantly because I enjoyed making games.

I'm the one who thought of the time travel theme because it was easy to imagine enemies gradually getting stronger in each stage after defeating all the weaker enemies. And I thought it would make it easier to create stages if we went from old airplanes to futuristic airplanes.

Time Extension: Was Konami’s Video Hustler an influence on the project? When we spoke to Masahiro Inoue previously, he mentioned that game in relation to Time Pilot.

Yoshiki Okamoto: I joined Konami after Hustler was released. I knew of its existence, but at the time didn't understand the technology behind it. I only knew enough to be able to imagine how they used that technology to produce the characteristic way the balls fired off. At the time, Konami's hardware had a restriction on the number of sprites that could be used, and Mr. Harima designed some hardware that would artificially increase that number. But I think even after that there weren't enough sprites, so they used VRAM to display the balls shot by the player character. From what I understand, usually VRAM was used to display scores and things like that, but never moving objects. It just goes to show what a genius Mr. Harima is to even think of using that for free-moving billiard balls.

Time Extension: Did you think Time Pilot would be successful? And how did you celebrate its eventual success?

Yoshiki Okamoto: Honestly, I wasn't confident. I personally thought it was fun, but I had no real basis to think it would be a hit. [After it was successful], I got a slightly bigger bonus. But it was really only a very slight increase. It did give me a lot of confidence, though. Even now I'm glad I was put on the team that made Time Pilot.

Time Extension: What was the inspiration for Gyruss? What was the development of that game like?

Yoshiki Okamoto: Gyruss was inspired by one of Namco's huge hits at the time: Galaga. I didn't like how you'd get driven to the edge of the screen in Galaga and then end up getting hit by enemy bullets, so I wanted to get rid of that edge, and that's how the idea for Gyruss started.

Development for Gyruss went pretty well. We were given a short development time from the start, so we had to pull a lot of all-nighters, but the team all got along well, so it wasn't terrible. It performed really badly in Japanese playtests, so we were worried it wasn't going to sell. But thankfully it sold well overseas, so we still managed to meet our projected sales number.

Time Extension: Gyruss memorably features an arrangement of Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565. Whose decision was it to include this?

Yoshiki Okamoto: I also love the music in Gyruss. It felt like it really stood out at the time. Mr. Kōzuki (the chairman) is the one who had the idea to do rock arrangements of classical music.

Time Extension: Gyruss is still not available on the Nintendo Switch. Would you personally like to see it come to Switch?

Yoshiki Okamoto: Yes, it would be great if it was made available on the Nintendo Switch.

Time Extension: I’m curious, you mention Mr. Kōzuki. What was Konami’s president like at the time?

Yoshiki Okamoto: Mr. Kōzuki was the founder and chairman of Konami. I think he was still pretty young at the time, but he was in a far higher position than me. I was a rookie hired fresh out of college, so I didn't have many chances to talk with him because he was the head of the company.

I remember him being very harsh to overweight employees. He would come straight out and say stuff like, "If you gain any more weight, I'll fire you." Apparently, he was of the mind that people who work hard don't gain weight.

Time Extension: Before leaving Konami, you worked on one more project for a period time: Time Pilot '84. What was the original plan for that game? How much did you get done before leaving the company?

Yoshiki Okamoto: It was planned as a sequel to Time Pilot. Our goal was to make the graphics on par with Xevious. I had intended to leave Konami after Time Pilot '84 was completed, but I was suddenly advised to quit, so I gave up on completing it and resigned from the company, leaving everything I'd worked on behind. All the characters were completed. I think the backgrounds were finished, too. But I was worried that the program would end up too big to fit on the hardware.

Time Extension: As a last question, I'm wondering, why did you leave Konami?

Yoshiki Okamoto: I worked for Konami as a regular employee for a year and a half. Before that, I worked as an intern (college part-time job) for half a year. To be frank, I quit because the salary was too low. I'd clearly been doing good work but didn't get a raise or anything, and I didn't like that Konami operated that way. So I felt that there would be no benefit to me to stay at a company like that for any longer.

Gyruss's main programmer quit around the same time and Mr. Kōzuki's only response to that was, "If you're going to quit, then hurry up and quit." So the programmer responded, "Fine, but I'll be taking Okamoto with me!" And just like that, I was dismissed from Konami. Because Konami fired me, I looked for another game company and ended up at Capcom.

Masaaki Kukino - Designer/Director/Artist

Masaaki Kukino joined Konami in 1986 as an artist and designer but eventually found himself directing a bunch of arcade games like Surprise Attack, Asterix, and Run and Gun, as well as the sniper game Silent Scope. Following his departure from Konami, he formed the company Game Wax in the UK in the early 2000s, before working at SNK and a Chinese arcade company named Wahlap. He now runs a studio in Kyoto called Glam Slam Games.

Time Extension: To begin with, it would be interesting to know — how did you first hear about Konami?

Masaaki Kukino: When I was in college, I played Time Pilot a lot at an arcade in Kyoto. I only learned after I was hired that Time Pilot was a Konami game, but in any case, that was my first encounter with Konami. To be honest, I had no idea Konami even made video games until my interview with them.

Time Extension: Do you remember how you got hired at Konami? What was Konami like at the time?

Masaaki Kukino: I heard about Konami from a college friend, and the job seemed interesting, so I took the entrance test. I was actually a student at an art college, so my initial goal was to become a clothing designer, but after learning about Konami I became more interested in that kind of design.

I also interviewed with Nintendo at that time, too, but it was back when the Famicom had only just been released and wasn't a huge hit yet, so Konami seemed more interesting to me. Once I heard I'd passed Konami's test, I decided not to take Nintendo's test. That was probably the biggest mistake of my life.

At the time, everyone in Konami's development department worked late into the night, so I too pulled multiple all-nighters as an artist after being hired, but honestly, everyone was so driven that it was kinda fun.

Time Extension: After getting the job, what was the first game that you ended up working on at Konami?

Masaaki Kukino: It was an [unreleased] off-road motorcycle racing game titled Super Bikers/Full Throttle. During on-site testing in America, the motorcycle input device broke and development was cancelled.

It was basically set up so that if you pulled the handle toward you, it would cause you to jump in the game, so we were running durability tests for it, but during those tests, the players were too forceful with it and it snapped. It would've cost a lot of money to remake it, so the arcade development boss at the time decided it would be too difficult to produce and cancelled the whole thing.

Time Extension: After Super Bikers/Full Throttle, what were some of the other games you worked on at the company? Do you have a favourite project?

Masaaki Kukino: I liked them all. Development was tough, but I had a great time. Some of the major ones were: Crime Fighters, Asterix, Slam Dunk/Run and Gun, and Silent Scope 1/2/3/SWP.

Time Extension: You just mentioned Crime Fighters, which was a title you worked on as both an artist and a designer. Do you have any good memories of making that game?

Masaaki Kukino: Crime Fighters was very fun to develop because I was able to create the game I wanted to create and I was blessed with the [right] team, so we were able to develop the game as we had planned. I designed the game and drew all the characters based on my knowledge of movie scenes and characters. I was especially satisfied with the stage bosses, each of which has its own personality. [With that project], I was also able to learn how fun it is to create games. That's why I believe it's one of my favorites!

Time Extension: Konami is known for its licensed beat 'em ups. Is Crime Fighters your favourite?

Masaaki Kukino: Yes, though it is not a licensed game, of course. I wanted to create a fun "beat 'em up" that four people could play together, with realistic battles that emphasized enemy characters' unique characteristics (like kicking defeated enemies, or finishing them off with a gun, etc.). It eventually became the basis for TMNT, X-Men, and The Simpsons that came after it.

I also like Asterix and The Simpsons too, as they were able to make the most of their characters and stories.

Time Extension: Speaking of Asterix, do you remember how Konami came to acquire the license for that game?

Masaaki Kukino: Konami Europe wanted us to create a game with the Asterix license, so we went to comic book publishers and theme parks in Paris, London, Milan, and Frankfurt for research, and did our best to recreate the kind of action seen in both the comics and the movies.

Time Extension: Can you tell us any more about Asterix's development? Do you have any fun or unusual stories from its production?

Masaaki Kukino: Asterix was my first visit to France for market research and interviews. I was smoking the French cigarettes Gauloises, and driving around in a Citroen 2CV. I bought a miniature car, took pictures, and went to the Asterix amusement park in the suburbs of Paris, where I enjoyed spending time outside of work during my stay.

One unusual thing was that, at the time, arcade game development was heading in the direction of researching only the American market, but this European market research gave me a hint that the European market is very different from the American market, not to mention the Japanese market, and that I could learn about the cultural differences in each country in a tangible way. This experience would have been difficult if I had stayed in Japan.

I'm also proud of the fact that with that project a French writer once told me that French players believe this game was made in France, and that I had the opportunity to portray the characters of Asterix and Obelix, even if only for a little while. It was interesting, too, to learn about the characters of French national comics, which are almost unknown in Japan and the U.S.

Time Extension: Were there any licenses that you remember Konami turning down or that you couldn't get? If so, what were they?

Masaaki Kukino: I don't know much about things other than what I was involved in, but I was at one point planning to license Tim Burton's Batman for the Arcades. I couldn't do it though because other companies got in the way. I also wanted to license the NBA, but again wasn't able to.

Time Extension: Out of all the games you developed at Konami, what was the most difficult to make?

Masaaki Kukino: I'd say the basketball game Slam Dunk/Run and Gun is definitely one of them. We had to account for all the different playstyles (1 vs. 1, 1 vs. 2, 2 vs. 1, 2 vs. 2), on two monitors, with four controllers, all processed with only one printed circuit board, as opposed to two.

It was a system that allowed someone to play on the second cabinet at any time even if someone is already playing on the first cabinet, as well as allowing them to face off against each other at any time. Plus, the 2D graphics are processed into 3D.

From a sales perspective, it's structured so that we receive the income of two cabinets from just one cabinet (one printed circuit board). And I worked extremely hard on the 2D pixel art. Also, the on-site testing was held in Chicago when the Bulls won their first three-peat (winning three championships consecutively), so that had a huge impact on our testing, too!

Time Extension: Obviously we couldn't talk to you without mentioning Silent Scope. Could you talk a little about those games? How did you come up with the premise for the series? Was it another difficult one for you to work on?

Masaaki Kukino: Silent Scope is a sniper shooter where you aim the miniature LCD monitor inside the scope (a zoomed-in image) at the main monitor (an image seen with the naked eye). This was completely new technology for arcade games, so yes, it was really challenging to pull off.

We were thinking at the time about whether we could create a new arcade game system using the 2-3 inch color LCD monitors of mobile phones, so we came up with the idea of a sniper rifle shooter in which the player searches for a target and shoots at a scene displayed on the monitor. I designed the game to focus on searching, aiming, and shooting, with the small LCD monitor built into the scope of the rifle, displaying a screen zoomed in with the camera, creating a greater sense of space between the gun and the main monitor.

The first Silent Scope gave me a sense of fulfillment in creating something new through repeated trial and error. I was also really satisfied with the exhilaration of using headshots to defeat enemies and bosses with one shot.

A bunch of players had a great time with it, and it was even introduced on a Japanese TV show. After that, we turned the game into a series.

Time Extension: Sadly, we've come to our final question, why did you end up leaving Konami? And what have you done in the years since?

Masaaki Kukino: I left in 2002 and created an arcade game development studio in London. I've always loved British music, movies, fashion, cars, culture, and all of that since my student days, so I wanted to live in London someday. I was able to build a career at Konami, but I decided to make that a turning point for my career, so I left Konami in order to make a development studio in London with some acquaintances. In 2006 I returned to Japan and became the producer of The King of Fighters 12 and 13 at SNK. After that I worked at China's top arcade manufacturer, then I founded Glam Slam Games LLC.