Today marks the 20th anniversary of the PSP. We're republishing this piece to celebrate that fact.

It's easy to forget that not so long ago, Sony was celebrating the fact that for the first time in decades, Nintendo's dominance in the realm of portable consoles had been well and truly challenged.

While the PlayStation Portable didn't outsell the Nintendo DS – Nintendo's machine sold a staggering 154 million units globally – it still managed to get a whopping 82 million consoles into the hands of players all over the globe, far eclipsing anything that Sega, Atari, SNK or Bandai had previously managed in the same sector of the market.

The PSP was a vital disruptive force in what had become a predictable part of the gaming arena, and its success not only created a widespread interest in mobile gaming that went beyond Nintendo fandom, but also encouraged studios such as Capcom, Namco and Konami to produce handheld titles that more than rivalled home console games when it came to sheer spectacle and playability.

With the PS Vita in its death throes and Sony's retreat from the portable sector all but complete, now's as good a time as any to look back on one of its most successful – and innovative – pieces of gaming hardware.

"Walkman of the 21st Century"

The handheld gaming sector at the dawn of the millennium was, by and large, as it had been for some time: ruled by Nintendo. The company had gained valuable experience in the nascent portable gaming sector via its line of LCD-based Game & Watch titles in the '80s, and by 1989, had released the Game Boy, which used low-cost monochrome display technology and interchangeable cartridges to effectively create the handheld gaming market overnight.

It was reported in David Sheff's seminal 1993 book Game Over that a high-ranking Sony manager actually berated his staff upon witnessing the incredible success of the Game Boy, angrily stating that it should have been a Sony product. Sony was, at this point in time, a major player in the portable entertainment arena thanks to its phenomenally popular Walkman line of personal cassette players, and had expanded its business to encompass portable CD players and televisions. To see Nintendo – a company with relatively little experience in the consumer electronics industry – soak up sales that could potentially harm Sony's Walkman business was clearly galling for the Japanese tech giant.

However, Sony wasn't in a position to challenge Nintendo at that time. It had only made minor inroads into the gaming industry via its publishing arm Sony Imagesoft, and, in the early '90s, was aligned with Nintendo on the SNES CD project, which would later be known as the PlayStation. When Nintendo left Sony at the altar and instead leapt into bed with rival Philips (only to then abandon the SNES CD concept altogether), the wheels were set in motion for a seismic change in the home gaming arena. Sony would continue to develop the PlayStation on its own, eventually releasing the 32-bit, CD-based system in 1994; it became the lead console of that generation and laid the foundation for Sony's continued success.

First the Home, Then the Handheld

With its status in the games market assured, Sony was in a better position to expand its hardware range, and in 2003, it was confirmed that the company was working on a portable system. With the incumbent Nintendo still adopting the "Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology" approach that had served it so well since the release of the Game Boy, Sony's ambitious plans for its handheld caused shockwaves. Right from the start the company positioned the upcoming system as a technological triumph; unlike the relatively crude and 2D-based Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance, Sony's machine would offer advanced 3D visuals and extensive multimedia capabilities. The 'father of the PlayStation' Ken Kutaragi boldly predicted to journalists at E3 2003 that it would be the "Walkman of the 21st Century", a clear sign that Sony's hopes were sky-high. It had conquered one sector of the portable entertainment industry before, and fully intended to repeat the trick in the handheld console market.

Later that year, the first mockup images of what would be called the PlayStation Portable surfaced. With its glossy exterior and sleek lines, it was the antithesis of Nintendo's brightly-coloured and toy-like handheld hardware; promotional imagery showed people walking around with units strapped to their necks via lanyards, playing games, watching films and listening to music. In the time before MP3 players were widespread and smartphones had yet to take over our lives, the promise of a system that could cover all aspects of entertainment – games, movies and music – was tantalising indeed. By the time Sony unveiled the final design of the PSP, it looked a little less futuristic and more functional; the buttons didn't sit as flush in the casing, and it was less sleek, but it still looked utterly, utterly gorgeous. A release date was confirmed for the end of 2004 in Japan.

In the face of this impressive announcement, Nintendo also confirmed that it was working on a successor to its popular Game Boy Advance system. Early rumours suggested that the company was looking to employ a unique dual-screen approach not entirely dissimilar to its Game & Watch consoles from the '80s; the news was met with a surprising amount of derision, and there was a definite feeling that the tables were about to be turned.

Just as Sony had gatecrashed the home console market in 1994, it seemed that Nintendo's hold over the handheld sector was about to be relinquished. When it became clear that Sony's console was superior in terms of raw power, this feeling only increased; images of the rather dumpy clamshell design of the DS did little to engender any confidence, and screenshots suggested that the unit's 3D power was roughly on par with the original 32-bit PlayStation. An upset was in the offing.

Of course, Sony's technological advantage came at a cost. The PSP launched at a higher price point than the DS, which proved on one level that the company had failed to grasp what made Nintendo's handhelds such a mass-market proposition. However, this didn't seem to make much of a difference initially as the PSP was met with incredible demand in Japan, North America and Europe; in fact, the European release had to be delayed because Sony wanted to ensure that it didn't have disappointed customers in its homeland and the US.

The strong commercial reaction to the system was encouraging, but the battle between Sony and Nintendo didn't go quite according to plan. Like the PSP, the DS also performed well right out of the gate, buoyed by the surprising response to the system's unique touch-based interface. While the dual-screen concept was perhaps underused, many titles leveraged the touchscreen for unique and intuitive gameplay which would foreshadow the explosion of interest in smartphone gaming a few years later.

Looks Aren't Everything?

Despite strong showings from both consoles, the DS started to open up a lead over its rival. It became clear that while Nintendo's console offered a new way to play, the PSP was exactly what it said on the tin: a Portable PlayStation. While the quality of the games wasn't up for debate, the system was essentially hosting very similar experiences to those you could play on your TV (a problem the PS Vita would suffer from much later on).

The initial batch of titles – including WipEout Pure and Ridge Racer – weren't followed up by quality AAA releases anywhere near fast enough, either. As a result, Nintendo's system appeared to have a more diverse and playable library of games, at least to the casual consumer.

Then there were worrying reports about the design and reliability of the PSP, with many launch systems exhibiting 'dead' pixels, something Sony was reluctant to consider a genuine fault. Another complaint related to the console's square button, which – when the unit was opened up – was found to actually overhang the side of the LCD display. Sony Computer Entertainment boss Ken Kutaragi famously defended the decision, saying:

I believe we made the most beautiful thing in the world. Nobody would criticise a renowned architect's blueprint that the position of a gate is wrong. It's the same as that.

It was a response that reeked of the same kind of arrogance that would cause Sony problems in the PlayStation 3 era, and it wasn't much of a shock when the PSP received its first facelift in 2007, the PSP-2000 (or "Slim & Light" as it was known in Europe).

Sony would tinker with the PSP hardware on more than one occasion and even managed to fit in TV-out and a mic into later models, but once again, it was hamstrung by the fact that Nintendo seemed to be doing everything right with its DS hardware; the launch of the attractive and very Apple-like DS Lite in 2006 solved perhaps the biggest problem with Nintendo portable – its looks – and a flood of best-selling games soon followed.

By 2007 the DS had sold almost twice as many consoles worldwide as the PSP (approximately 40 million to Sony's 25 million), and every studio worth its salt had DS titles in development. However, like all tides, this one had to turn eventually.

Take Me to the Movies

Kutaragi's early statement about creating another Walkman wasn't mere bluster; Sony was adamant that the PSP would do much more than just play video games. Early bundles came with an in-line remote control for music playback on the move, while the console's proprietary Memory Stick PRO Duo format could be used to upload songs and albums. These sticks could be upgraded for higher-capacity versions, too. When you consider that the average mobile phone available at the time had a tiny storage capacity for music and other files, this was quite a selling point.

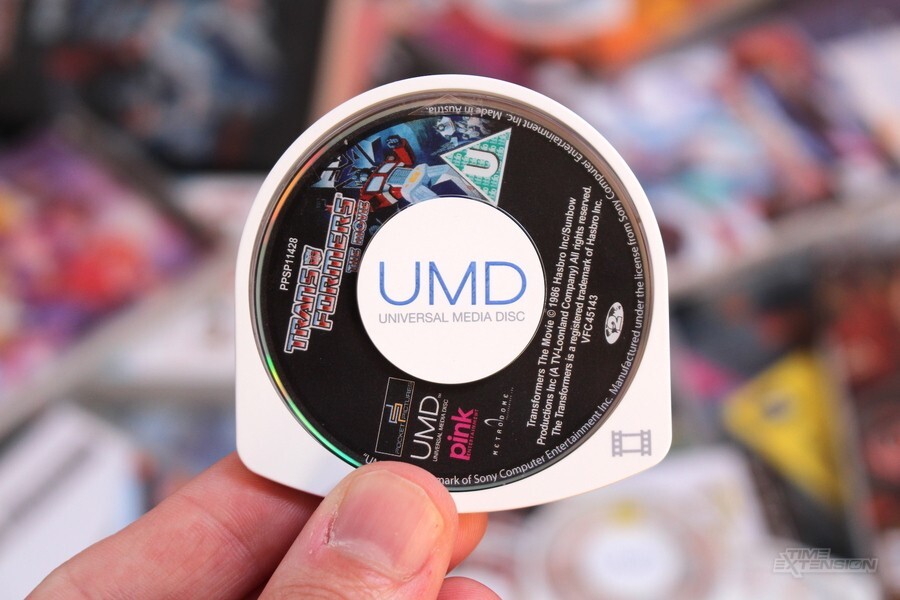

However, the most bold signal of Sony's intent was its approach to movies. The PSP used optical media as its software delivery method, allowing for massive games with FMV and high-quality music. These discs also allowed Sony to create its own media format. Universal Media Discs were, as the name suggests, capable of holding more than just game data, and Sony wasted no time in encouraging major Hollywood studios to sign up to support the format. While the screen was standard definition in terms of resolution, it was quite an experience to have digital movies in the palm of your hand.

Sadly, the UMD format was destined to go the way of Betamax – another famous Sony-made flop – because the public wasn't convinced. UMD movies were high-cost and could only be played on the PSP itself; to make matters worse, they lacked the bonus features present on the (cheaper) DVD editions. Low sales forced Universal and Paramount – two of the big supporters of UMD in the early days – to withdraw support, and by 2006, retailers began phasing out the format in their stores. Sony couldn't rely on films to sell the PSP, but thankfully, games were about to save its bacon.

What's That Coming Over the Hill?

Capcom's Monster Hunter series may be massive today, but during the PSP, it was merely bubbling under. The company supported the PSP with Monster Hunter Freedom, a launch title in Japan, and followed that up with Monster Hunter Freedom 2. With its powerful internals and wireless ad-hoc capabilities, the PSP was the perfect platform for Monster Hunter's team-based social gameplay; by 2008, the series had reached smash-hit status in Japan, with Monster Hunter Portable 2nd G (known in the west as Monster Hunter Freedom Unite) selling 2,452,111 copies to be that year's best-selling video game in the region.

The PSP was gaining traction despite the runaway success of the DS, and the 'Monster Hunter effect' resulted in a swathe of software support from some of the industry's biggest players. Konami – which had released the turn-based Metal Gear Acid 1 & 2, as well as Metal Gear Solid: Portable Ops – was convinced to give PSP owners a full-fat Metal Gear experience in the shape of Peace Walker, which arrived in 2010. While Portable Ops was very much a down-sized adventure that focused on short missions that could be played easily on the move, Peace Walker was, for all intents and purposes, a fully-fledged sequel to the home console versions, packed with cut-scenes, content and epic storytelling.

It was this late burst of support – much of which was thanks to the amazing success of Monster Hunter in Japan – that allowed the PSP to close the gap a little on the DS. As we've already established, Nintendo's system was the clear winner in terms of sales, but 82 million PSPs sold is a figure not to be sniffed at; it's significantly more than the combined sales of the Sega Game Gear, Atari Lynx, NEC PC Engine GT, Bandai WonderSwan and SNK Neo Geo Pocket.

Sony was the first company to even remotely challenge Nintendo in the handheld market, and it's worth keeping in mind that the DS – like the Wii – was something of an anomaly; it had some amazing games but also sold millions off the back of casual titles, like the Brain Training series.

Collecting For The PSP Today

Due to its relatively young age, building a sizeable PSP collection is a pretty stress-free affair. You'll find that the system itself is quite cheap on the second-hand market, and software – both boxed and loose – is also cheap as chips.

Many of the system's best games are available for very little cash, and even the rarer and more desirable items won't cost you that much. There's the odd exception to this rule – R-Type Tactics: Operation Bitter Chocolate (yes, it's really called that) is a Japanese exclusive that sells for triple figures, for example. On the whole, though, you can amass an enviable PSP collection for a pretty humble sum of money, making it ripe for rediscovery – especially if it passed you by the first time around.

Titles like God of War: Chains of Olympus, Tekken: Dark Resurrection, Final Fantasy Tactics, Tactics Ogre, Breath of Fire III, Castlevania: The Dracula X Chronicles, and Gran Turismo are all well worth a look, and have aged surprisingly well – certainly a lot better than many Nintendo DS titles from the same time period.

Then there's the scope for retro gaming on the system; the machine played host to some incredible vintage compilations such as Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded, Capcom Classics Collection Remixed, Metal Slug Anthology, SNK Arcade Classics Vol. 1 and SEGA Mega Drive Collection.

A System Ahead of Its Time

Cradling the PSP in your hands today, it's hard not to be impressed by the machine's gorgeous looks and still-impressive library of games; it manages to feel like something from the future, rather than a relic of the past.

Indeed, there were elements of Sony's plans for the system that were perhaps too far ahead of their time; 2009's PSP Go – which ditched the UMD drive and went totally digital – made perfect sense on paper. Portable systems don't really benefit from physical media that has to be swapped out and could potentially be lost, so the Go's download-only approach made sense – just ask your average smartphone gamer, who has never had to worry about carrying all of their games around with them.

However, as the Nintendo Switch has proven today, people still love physical media, and back in 2009, the market was even less ready to take the all-digital route. The PSP Go was a noble experiment and a sign of things to come, but it failed to find favour with the gaming public.

With the Vita, Sony could be accused of perhaps being too comfortable in the past, however. Like the PSP, the system offered little that couldn't be found on a home platform, and with Monster Hunter defecting to the 3DS, Sony had lost one of its key allies in the handheld market. The Vita certainly deserved better and has been an excellent platform for downloadable indie games, but the market has moved on – a fact that even the mighty Nintendo has found, with its 3DS system falling way short of the sales of its forerunner.

Even Nintendo has had to find another niche to exploit, and its Switch system offers a unique approach by straggling the divide between handheld and home system. With the 'traditional' portable market a mere shadow of its former self, we'd highly doubt that Sony would ever consider another dedicated mobile games console (although it has recently announced a companion handheld for the PS5) – but spending a little time appreciating the brilliance of the PSP truly makes us wish that weren't the case.